This 1903 Paris-Madrid report of Motor Age, titled Paris-Bordeaux, really gives the effective route of that City-to-City race. It’s a very complete and extended report of that dramatic race, even summing up names of the deceased and of the wounded people. Means, you’re invited to a fairy long, but interesting read with many specifics.

Text and photos with courtesy of hathitrust.org hathitrust.org, compiled by motorracingistory.com

MOTOR AGE VOL. III. No. 24. JUNE 11, 1903.

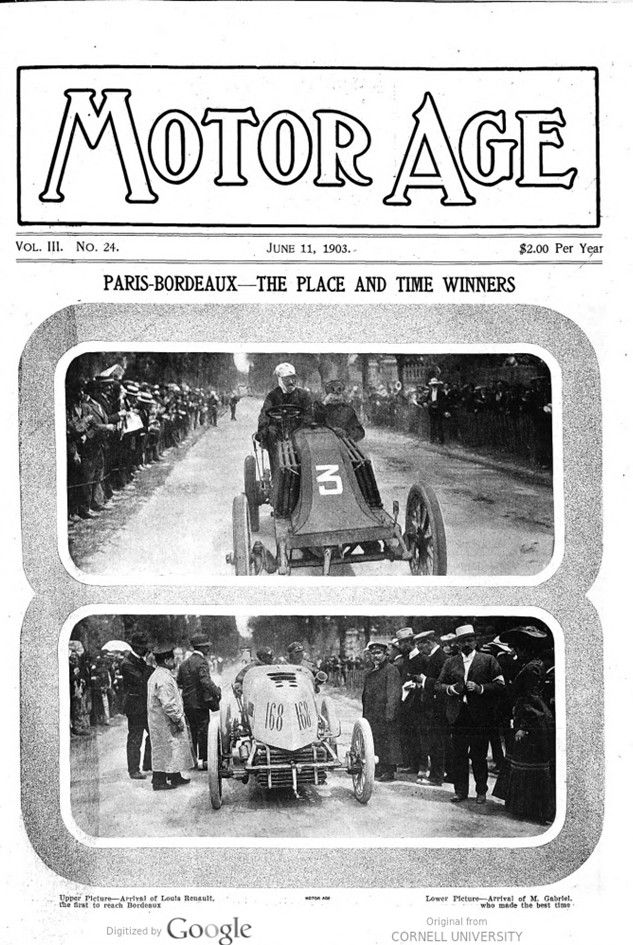

PARIS-BORDEAUX – THE PLACE AND TIME WINNERS – FROM PARIS TO BORDEAUX

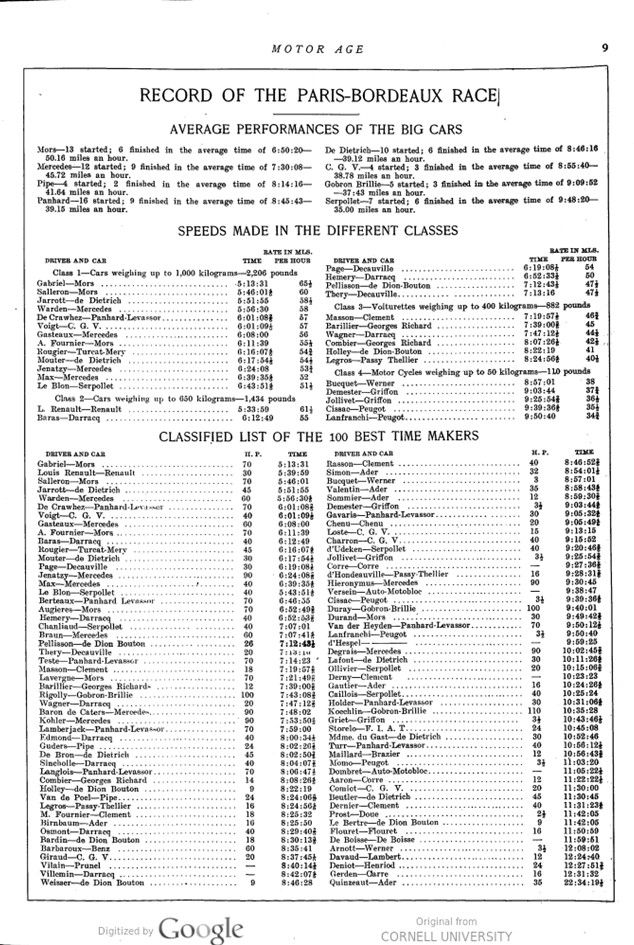

Paris, France, May 26 [Special Correspondence] – Despite its hasty termination and governmental interdiction at Bordeaux, the end of its first stage, 343 miles from the start, the Paris-Madrid race begun Sunday was without question the greatest of all automobile events and may even rest in history unparalleled. Not alone is this true because Gabriel, the winner of the first stage, and hence virtual winner of the unended race, broke Fournier’s record from Paris to Bordeaux by driving his 90-horsepower Mors car the 342 miles in the corrected time of 5 hours, 13 minutes and 31 seconds; speeding at the rate of 95 miles an hour on some down grade, straight stretches; working up through the long line of swiftly darting competitors from one hundred and twenty-first position at the start to third position at the finish, and thereby having overtaken and passed all of the 118 men and cars ahead which had remained on the road.

But in the number of starters; in the close competition; in the average speed; in the great concourse of people who lined the whole route and bunched into great throbbing hearts of human interest at each end; in the very fierceness of the struggle itself; in the giant powers of the cars; in the array of brilliant automobilists, and in the interest which reached from one end of continental Europe to the other, swept the Atlantic, pierced the habitations of princes of power and of wealth and drew the peasant from his cottage in all these features, with- out taking into account the actual performance of the winner and without touching upon the accidents which recorded its danger, brought about its sudden ending, and which have shaken newspaperdom wherever cablegrams go the Paris-Madrid race ranks first in the list of automobile events of the world.

Paris-Madrid in title, Paris-Bordeaux in reality, the race, by whatever name it be called, was so great that it was too great. Ended after the worst had happened, it might have proceeded with thinned ranks clear to the capital of Spain without being greater. Those 343 miles of the most trying struggle in the history of speed, the fiercest battle for supremacy in the history of sport, marked a decisive epoch in automobiling – the time when an unlimited field of racing automobiles be- comes too mammoth in every way to be handled on the open road, protected only by temporary marshaling.

The race was run at a terrible cost-unfortunate in reality and unfortunate for automobiling and the automobile industry. Its mark of misfortune must accompany its mark of greatness into the records of the sport. Dubbed a holacaust of Hades, it has taught a lesson clearly and sharply silhouetted against the background of world-wide automobiling. It has shown where the battles of sport be- come battles in earnest-in fact.

——-

THE BEST PERFORMANCES

Gabriel was indeed a winner. The magnificent manner in which he guided his huge car so successfully through the hurricane of dust thrown up by the hundred and more hurrying. drivers whom he passed, to miss by but two places the honor of first finishing position at Bordeaux, would alone sustain his laurels. Then by comparing his average rate of speed of 65 miles per hour with the average rate of speed at which Jarrott, with a 70-horsepower Panhard, won the Ardennes circuit last year, the real greatness of his long, non-stop run is established. For Jarrott, in that other race, averaged but 54 miles an hour; and Gabriel himself, second to the Briton, but 53 miles an hour. Thus 12 miles an hour faster did he fight his way through a field of over twice the size and come within but a few minutes of winning both first place and first time.

But though Gabriel’s performance was the most striking, because of the number of competitors overtaken and the time made, that of the first man to pass the scorers at Bordeaux – Louis Renault, who, with a light Renault car, well within the weight limit of the 650-kilogram, or 1,430-pound, class pushed his way to the front to rank second time winner of the first stage – was a surprising and heartily received achievement. Renault’s net time was 5 hours, 33 minutes, 45 seconds.

M. Salleron, who drove a 70-horsepower Mors of the heavy class, secured third time honors, driving the race in the corrected time of 5 hours, 45 minutes, 1 seconds. Jarrott, first to start and second to reach Bordeaux, ranks fourth, with the time of 5 hours, 51 minutes, 55 seconds credited to him.

—–

THE SPECTACULAR START

The start of the race was in every particular one of the most spectacular affairs that has ever been enacted in connection with a sporting event. It was a magnificent eight in which all of the ginger and activity of its official conduct mingled with the careless. abandon of the sightseers to effect a queer contrast of strenuous intent and pure gayety.

Picturesque, grotesque, indescribable was the road from Paris to Versailles on the day preceding the start. There was one unbroken procession of motor cars, bicycles, carts and people on foot, all gay and happy, out to have a good time and having it. A hundred thousand bicycles, each carrying a lighted pink or green Chinese lantern, dotted the road, like giant fireflies. In and out among the constantly moving crowd, hundreds of automobiles picked their way without accident, showing the marvelous skill of the drivers. Women and men mingled in careless abandon, the cafes being crowded the whole night long, and few indeed sought to sleep. It was a characteristic French crowd and the carnival spirit was at its height.

With memories of the troubles of Marie Antoinette still clinging to its picturesque environment, the garden of the Trianon sounded till morn an unceasing reveille of automo-ile, motor bicycle and bicycle bells, horns and squawkers. With its streets bulging with hilarious humanity, a large part of which in true European style made a midnight picnic in the streets and squares to the noise of interminable jesting, chattering and general merry making, to the smell of much begarliced sausages and to the flourish of wine bottles; Versailles itself was one great flame of artificial light, vari-colored and more like that of a great national celebration than that of the eve of a mammoth sporting event.

There was no such thing as sleep for the racing men, the officials, the great army of newspaper men and others actively or indirectly interested in the details of the start. The hotels were unable to find beds for the thousands; hundreds upon hundreds slept out of doors during the dry, warm night, or passed the tiresome hours before the morning activity without sleep. About 500,000 persons congregated in Versailles and stretched away along the first few miles of the route. The police, the gendarmes and the soldiers lent their activity to the general confusion, and in the midst of it all the actual contestants waited – waited for the time of their great efforts to commence. The officials of the race worked and slaved to prepare everything that had to be prepared for a successful start. Sleep to those who needed it most for the task of the morrow could have been but a nightmare.

At 2:30 Sunday morning, with the lights of the town just beginning to lose their brilliance in the real day peeping bashfully over the tree lined horizon, a hearty breakfast was served to the contestants and officials. Then the vanguard of the racing contingency – such men as Gabriel, Fournier, Rene de Knyff, the brothers Farman, C. S. Rolls, Mark Mayhew, W. K. Vanderbilt, Baron de Caters, Lorraine Barrow, Baras, Renault and Charron – accompanied Jarrott to the spot where he was to start his great 85-horsepower de Dietrich first on the way to Bordeaux.

The St. Cyr Rambouillet Road leads south-westward out of Versailles and here the actual starting point was marked by a plain arch bearing the word „Depart,“ and festooned with the tri-colors of France.

Ready to view the start and then rush to catch a glimpse of the first arrival at Bordeaux, those on board the special Paris-Madrid train had waited all night. They were anxious and alert, however, by 3 o’clock when the officials of the Automobile Club of France announced that everything was in readiness. Only the surging of the crowd made confusion at the tape which stretched across the road under the slightly waving arch. The spectators almost fought to be near the line and the police were unable to clear any but an extremely narrow racing highway between the crowds on either side. Dangerous it was and the racers complained, saying that it would be impossible to run at full speed through such waving lines of irresponsibility. In fact, even after the first few starters had marked out the way and shown the danger of close proximity to their great cars, the crowd still pressed and pressed and only forced itself backward when a car ran extremely near.

From every side persons of all conditions endeavored to give him a spoken farewell and handshake when, white-capped and waterproof clad, the rather jaunty Jarrott appeared on the scene. It was a quarter after 3 o’clock and the more dignified lights were outdone by the rapid series of photographic flashlights which jumped and blazed as the picture men on all sides tried to secure the likeness of the Ardennes winner as he stood ready for the word to start this, the greatest of all motor races.

He drove his car up to the tape and hardly had ne pressed the stalwart Fournier’s hand in a cheery parting, when a sudden explosion said „Get ready.“ Sixty seconds had Jarrott yet in which to seat himself well in his car, fix the goggles that were to keep the sand and dust of nearly 350 miles of travel from his eyes, and grasp the wheel and levers.

Then another nerve thrilling report and an excited official shouted „Allez.“ It was the word to go. Down went the pedal under Jarrott’s foot, forward went the side lever and quickly moving and as quickly swinging into fourth speed the leviathan car swept into the unknown fight.

With shouts of good luck and cheers still ringing after the dust enveloped Jarrott, the devil-daring, experienced and much whiskered, Rene de Knyff, chevalier by right of his prominence in motor racing, drew to the position of ready. „Forty-five seconds, 30 seconds, 15 seconds,“ drawled the starter-then quickly „Go,“ and the heavy Panhard shot down the course – with driver and car truly a pair of old-timers.

The flashlights had ceased, for in the broadening daylight the industrious photographers had resorted to slowly burning magnesium ribbons and then to the sun’s own illumination. The first tremor of excitement past and the warm breath of sunrise dashing nervousness out of the many sleepless eyes, the officials settled down to sending away and the crowd to seeing go, the hundreds of other fame seeking motorists, one of whom promptly on each minute dashed after the leaders.

In order, Louis Renault, on a 30-horsepower light Renault; Thery on another extremely light car, a 20-horsepower Decauville; Lorraine Barrow on a heavy de Dietrich, similar to that on which Jarrott had paved the way, and Fournier, the favorite, with a 90-horsepower Mors, got under way nicely.

Especially interesting among the unlucky ones at the start were W. K. Vanderbilt, Jr., H. S. Harkness and M. Charron. Vanderbilt was a minute late in arriving and then the officials, with characteristic French desire to do a little talking, both with mouths and hands, held him back a minute longer. Soon after being given the word to go; he lost control of his car in the crowd, but was able to steer clear of actual accident. But his poor luck followed him throughout the race and he was one of the early withdrawals, dropping out at Chartres.

Especially among the American and English colonies much interest had been evinced in the Harkness home-built racer, on account of the car having been originally made to compete in the preliminary trials for positions on the American Gordon Bennett race team. Thus the non-appearance of harshness was credited as a disappointment. Charron had counted upon driving one of the big eight-cylinder C. G. V. cars in the race, but did not get the car weighed in on time. Hence he was forced to drive one of the small 40-horsepower C. G. V. cars which had been entered and properly weighed in for another driver.

Madame du Gast, true Parisian, handsome enough, self-possessed, the only woman competitor, made a hit as she drove up to the starting line in a flower decked, 35-horsepower de Dietrich. She wore a gray coat with gray hood, ear lappets, and the typical mask and goggles.

Thus, amid the cheering of the crowd and the repeated singing of „Viens Poupoule“ and songs of the Parisian boulevards, the long line of prominent and of unheard-of racers stretched its length Bordeauxward and, as it was then thought, Madridward.

At 5:50 o’clock 138 large cars had started. Then began the starting of the voiturettes, thirty-six of these being sent off in as many minutes. Motor bicyclists . then claimed the attention of spectators and officials and fifty-three were started by 6:50 o’clock, when the last camera was snapped upon the departing line, the last farewell shouted and an undignified but animated rush of officials, newspaper men and prominent motorists was made for the special race train.

Although several Americans and Englishmen had started as drivers of continental cars there were no American cars in the race, while the only British cars represented were the Wolseley and Napier-and neither made a good showing. It was in reality a Frenchman’s race on French soil, run with French enthusiasm and abandon – and it was on in earnest.

—–

THE ARRIVAL AT BORDEAUX

The special train arrived at Bordeaux at 11:30 o’clock and the interested ones who poured from it were met with the report that as yet there had been no signs of the arrival of the racers.

The control where the finish of the first stage was to take place is about 4 miles from Bordeaux. From this point there was a view of the course for over half a mile. The road was roped off for some distance on both sides and was under strong military guard. The crowd, anxious from long waiting, irritated by the heat and excitement, and ignorant of the progress of the race, was hard to manage, and the soldiers had all they could do to keep the course clear. The air was surcharged with suppressed excitement and the nervousness of the spectators was heightened by the constant bickering with the soldiery.

It was shortly after noon that a bugle, away down the road, sounded clear and strong above the noise of the crowd. The first. had been sighted. Then a whirl of dust arose over the hill which marked the limit of vision, and down the incline shot a car-what car? Up the grade toward the control swung the vehicle and at exactly 12:14:45 Louis Renault, third starter, halted by the automobile club officials.

Great was the surprise that this light car, with its comparatively small motor, should have succeeded in passing two of the favorites and in then holding aloof in front, for no other rushing competitor was seen coming oyer the hill. Great, also, was the acclaim with which Renault was greeted. Dust-covered till almost unrecognizable he modestly received his cordial welcome and joined the waiters and watchers.

During the quarter-hour that elapsed before the second arrival was sighted, reports of accidents along the line began to come in. They were disquieting to the gathering at the end of the first stage of the race, but for the time being relief from fear of their consequences was sought in the always present hope that much exaggeration had been indulged in by those who had sent the messages over the wires.

At 12:30:55 Jarrott rode into a welcome equal to that given Renault and the first to grasp his hand was Edge, his compatriot on the British Gordon Bennett cup race team.

More reports of accidents were given out and then as each succeeding car arrived its driver was eagerly and anxiously questioned concerning the character of the ride and of his knowledge of accidents.

Third came the winner, at 8 minutes 31 seconds after 1 o’clock. When the high number on his car was noted and rapid calculations made of the number of contestants he must have passed in order to reach Bordeaux third it was but a moment before popular acclaim made him time winner for that stage of the race and the voice of the people was right.

The next wait was shorter, 5 minutes, and Salleron, on a Mors, rode in for fourth position and third best time. Thirteen cars reached Bordeaux prior to 2 o’clock, among them being a Panhard driven by Berteaux, a Serpollet steam car driven by Le Blon, a Mercedes driven by Jenatzy, a C. G. V. driven by Voigt, a Turcat-Mery driven by Rougier, another Mercedes driven by Warden, another Panhard driven by de Crawhez, and a Darracq, using alcohol for fuel, driven by Baras.

Baron de Caters was the first to arrive with a Gordon Bennet race car, when he brought his 90-horsepower Mercedes to the line. He was followed by a 40-horsepower Mercedes driven by M. Max, with Page on a Decauville and Chanliaud on a Serpollet close behind.

Twenty-four cars arrived before 2:45, among them being another Gordon Bennett possibility, Hieronymus, with a big Mercedes. Madame du Gast arrived at 5:30 with a few dusty, wind-blown blossoms sticking here and there on the car to remind those who had witnessed the start of the gala fashion in which she had departed on her difficult journey. She was, of course, given a hearty welcome. Incidentally, Madame du Gast was the only woman to compete in the racing section of the big Paris-Berlin event.

By 6 o’clock only sixty-eight of the 216 starters had arrived, and up to 7:30 Jarrott was the only American or English driver to reach Bordeaux. After 6 the cars came straggling in and by midnight a little over а hundred had finished. The entire list of finishers of the first stage was close to 110-about half of the great brigade which so enthusiastically left Versailles just as the sun peeped over the trees.

—–

WEIGHING IN THE CARS

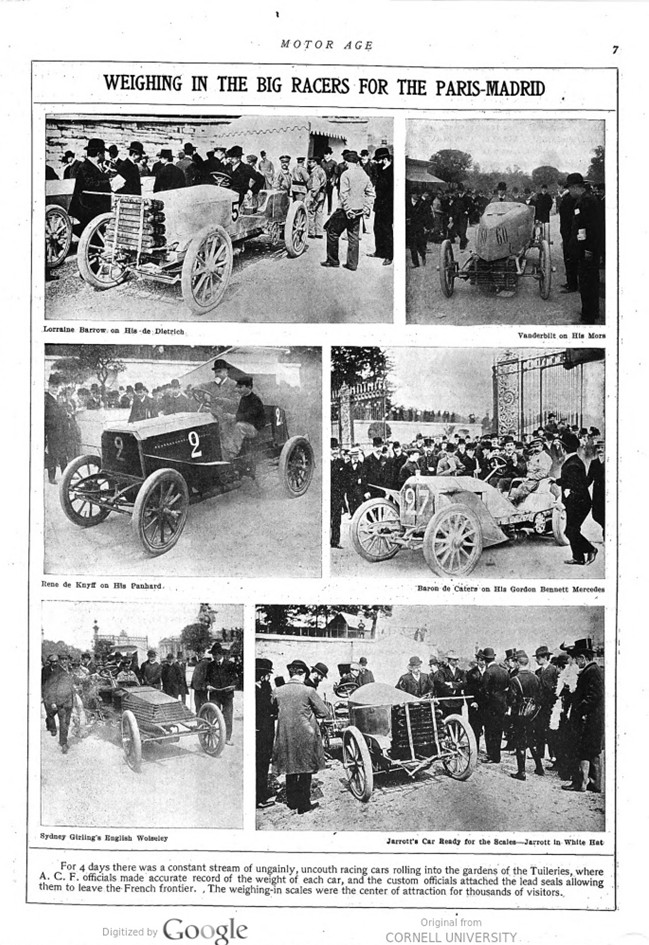

The officers of the Automobile Club of France passed 300 automobiles and motor cycles over the weighing scales during the week ending on the Friday prior to the Sunday start. This weighing occurred in the gorgeous gardens of the Tuilleries, the French government not only having offered the ser vices of a squad of customs officials but having also donated the use of these swell grounds to the automobile club.

A portion of the gardens had been railed off not more than a couple of minutes’ walk from the home of the Automobile Club of France in the Place de la Concorde, and a pair of platform scales, each capable of handling cars weighing a ton or more, were mounted on posts sunk into the ground. Over these scales passed the most varied assembly of high-powered cars ever brought together, each in strict racing trim, with nary a pound of extra metal or wood or leather.

In order to abide by the rules each car was driven onto the scale by the driver who was destined to negotiate its course in the race. Club officials handled the scales and made accurate records of the total weight of each vehicle. Then the customs officers took each car in hand as it was driven off the scale, and by attaching a small lead seal gave it the right to leave the French frontier and to return thereto without friction with local authorities. When the signature of the actual driver of the car had been attached to the customs documents the weighing in formality was ended. The cars were weighed in the order of their starting number.

During the whole 4 days of the weighing in the gardens were crowded with interested persons of all nationalities, come to see the giant racers, many of which were out for business for the first time. Talk of the race and of the respective chances of the cars was constant, and favorites were picked and repicked galore. The racers were pointed out and the French public stared at the American and English drivers, while the English and American visitors were equally anxious to see what manner of men might be the great Frenchman who had driven in so many notable events.

—–

CONDITIONS AND RULES

The fastest car to arrive at its destination was not the winner of the race, the conditions being somewhat different from those of previous events. The sporting committee of the A. C. F. decided that in the Paris-Madrid race there should be as much prominence given to reliability and regularity of running as to speed, basing the results upon the performances of teams of vehicles, each composed of four cars of the same make and type. action was taken to prevent manufacturers building exclusively for speed and trusting to luck to get one of a number of vehicles through without accident. On account of the termination of the race at Bordeaux, however, the elaborate system of averages which had been planned was not officially computed.

Most of the rules of the race were about the same as those which have governed previous similar events. Some of the most notable rules are below:

It was necessary for the car to be finished with a bonnet and some sort of body at the rear with the driver’s seat securely attached. It had also to have a muffier.

The car had to be in charge of the driver and his chauffeur after the start was made, all repairs on the road to be made by them without outside aid.

All repairs, inflating of tires and filling of tanks were including in the racing time.

At the end of each stage the car was to be placed under official supervision and the driver and his chauffeur not allowed to go near it until a few minutes before the start of the next stage.

Each car was fitted with a small metal box with a slot at the top, which closed with a hinged cover. The box was sealed. At each control a card containing the time of arrival and starting was to be placed in the box. These figures were also duplicated on sheets belonging to the control officials.

—–

THE ROAD ACCIDENTS

Near Libourne, Lorraine Barrow ran over a dog, the accident resulting in the death of his mechanician, who was hurled against a tree and his skull fractured. Barrow was also seriously injured.

At Angouleme M. Tourand attempted to avoid a child that ran across his path. A soldier ran forward to save the little one and was struck by the car and instantly killed. The shock threw the car against a tree, M. Tourand receiving serious spinal injuries and his chauffeur being killed outright. Two men standing near were run over by the car, one of them dying a few minutes later. The child escaped unhurt.

Lesna, old time cycle racer, who was riding a motor bicycle, fell and was seriously injured, probably to an extent that will prevent future cycling.

Mr. Stead collided with the rear wheel of M. Salleron’s car and was thrown into a ditch. Both he and his chauffeur were injured.

The lubricating pipe broke on Lieut. Mansfield Cumming’s car and the oil poured in and took fire, making it necessary to abandon the race.

Harvey Foster, driving a 50-horsepower Wolseley, collided with a cyclist and had to retire.

Mr. Austin, general manager of the Wolseley Co., was compelled to quit the race because a crosshead pin flew out and the connecting rod broke.

The engine and frame of C. S. Rolls‘ racing car almost parted, so that Mr. Rolls finished the trip to Bordeaux on a touring car.

The first and only accident to Marcel Renault, which resulted in his subsequent death, is best described by M. Seret, who drove Renault car No. 113 in the race. He says:

„Coming from the village of Couhé at 50 miles an hour at a sharp turn over a bridge spanning a river, I saw one of our cars overturned, and a wheel smashed. M. Marcel’s friends standing near told me he had dashed full speed around the double and very sharp corner, despite the fact that it was signaled dangerous by a sentinel waving a red flag. The car skidded and ran off the road. The wheel caught in a piece of drainpipe on the pavement, the car turned right around, a wheel was smashed, and the vehicle went full tilt for a tree, against which M. Renault was hurled with great violence.“

Georges Richard ran into a donkey cart on the Chaveau hill, near Angouleme, and broke several of his ribs, besides suffering other injuries.

The steering gear on Mark Mayhew’s car became uncontrollable and the car smashed into a tree with terrific force. Both he and his chauffeur were bruised, but not seriously hurt.

Mr. Terry, an American driver, in attempting to avoid a collision with Mr. Porter, ran his car onto the flint pavement and burst his front left tire. His gasoline tank took fire and he would have burned to death had not his chauffeur promptly dragged him from the car.

Mr. Porter, of Belfast, ran against a cottage when his car took fire from overheated bearings. He was thrown out and his chauffeur, M. Nixon, was pinned beneath the car and burned to death before Mr. Porter’s eyes, the latter being unable to assist him.

At Chartres, Fournier, Vanderbilt Baron de Forest abandoned the race, owing to slight damage to their respective cars.

Among the competitors the killed are: Marcel Renault, Wm. Nixon, Lorraine Barrow’s chauffeur, and Normand, M. Tourand’s chauffeur.

The seriously injured participants are Mr. Stead, M. Tourand, Lorraine Barrow, M. Georges Richard and M. Lesna.

—–

NOTES OF THE BIG RACE

Immediately after the interdiction of the Paris-Madrid race Charles Jarrott expressed the opinion that the decision was a wise one, as there were too many cars in the race and the speeds were too great. He said the enormous motors and light frames prove nothing of commercial value. He suggested for future races that the size of the motor be limited and a minimum weight be fixed, and the entries be limited to a reasonable number, with only carefully picked drivers.

Gabriel was indignant at the careless manner in which the route was kept and was surprised that there were not more accidents, because of the utter helplessness of the police and officials in attempting to restrain the crowd. He said the racing men were kept in constant suspense and alarm by seeing the rash spectators standing out in the road ahead, regardless of the fast-flying cars bearing down upon them.

An instance of the carelessness in policing the roads was witnessed near Choisy-le-Roi. A special train had been started from Paris to Vendome to accommodate people who wished to see the racers on the way. The railway guard had received no notice of the extra train and the gates were left open. As the train came rushing along a motor car containing two persons approached the track at fair speed, the occupants thinking there was no danger as the gates were open. Just before reaching the track they saw the train bearing down upon them and realizing that a collision was inevitable they jumped from the car, allowing it to go on. The engine struck it fairly and smashed it to pieces. The mechanic of the motor car was hit by a flying fragment and seriously injured.

The loss caused by the suspension of the race was enormous, conservative estimates placing it at $8,000,000. The cars. alone cost $2,000,000. The professional drivers had been paid high retaining fees by the manufacturers, repair and gasoline stations had been established along the route and no money had been spared to make the race a success. The losses of the Mercedes, Mors and Panhard firms are estimated at from $4,000 to $6,000 each.

When the impatient persons at the arrival control of Bordeaux saw the first car come rushing in, they utterly disregarded the threats and expostulations of the soldiers and crowded around the car as it slowed up. The driver was Louis Renault, and to the anxious inquiries concerning the other contestants his reply was: „A motorist, traveling at 60 or 70 miles an hour, does not notice other cars.“

Gabriel made a non-stop run in addition to breaking the record from Paris to Bordeaux.

Six of the seven cars started by Serpollet arrived at Bordeaux. An accident to the one driven by Rulot kept him and his mechanic working for 10 hours, but they arrived within the 24-hour-limit. They were without food or drink the entire journey.

The spirit of humanity was stronger than the desire to win the race in the bosom of Maurice Farman. When he discovered Marcel Renault lying unconscious by the roadside, he abandoned his chances of winning, and picking up the injured man, carried him in his car until surgical assistance was secured.

None of the accidents occurred within reach of the Red Cross ambulances, although elaborate preparations had been made by both the Spanish Red Cross Society and the Ambulance Association of France. Considerable aid was rendered by Dr. Tucker, of Paris, who took a first aid equipment on his car to Chartres, rendering assistance on the way.

The government effectually prevented the possibility of further accidents after the cars left Bordeaux. The racing cars were not permitted to use their own power. Some were towed by tourist cars, others were drawn by horses, and each car as it left was in charge of a policeman. The cars which were not returned by train were kept strictly within the legal limit.

Rene de Knyff used alcohol as fuel in his 70-horsepower Panhard. Baras also fed alcohol to his Darracq, and Rigolly treated his 100-horsepower Gobron-Brillie in the same manner.

The Mors, Renault, de Dietrich and Mercedes cars earned the laurels for speed, but the Ader cars secured one of the really great honors in constituting the only full team to go entirely through the first stage to Bordeaux. Not only the four cars comprising the regular team completed the trip, but a half dozen extra entrants, with Aders made good also.

Jarrott drove into the control as fresh and calm as if he had been taking a short pleasure trip. His chauffeur, Bianchi, was exuberant over the successful termination of this, his first great motor race.

The most ordinary precautions for safety along the route were neglected. The automobile club had guaranteed all expenses of keeping the course clear; but nothing was done. The level railway crossings were not kept open, the crossroads were not guarded, the gendarmes and rangers who should have been patrolling the route were not there, the buglers, who were to have been posted every 200 yards to sound the alarm of approaching cars, were not at their stations. Nothing was done to prevent the accidents.

Foto captions.

Page 1. Upper Picture-Arrival of Louis Renault, the first to reach Bordeaux – Lower Picture–Arrival of M. Gabriel, who made the best time.

Page 2. Scene at the Start – Edmond on a Darracq, Rushing Into Bordeaux – Jacquelin, the Cyclist. Taking Renault’s Ticket at Bordeaux

Page 3. Valentine, Ader, on Left-Bardin, de Dion, on Right, at Bordeaux. – Baron de Crawhez Bringing in the First Panhard to Finish – Flashlight of Henri Fournier’s Start

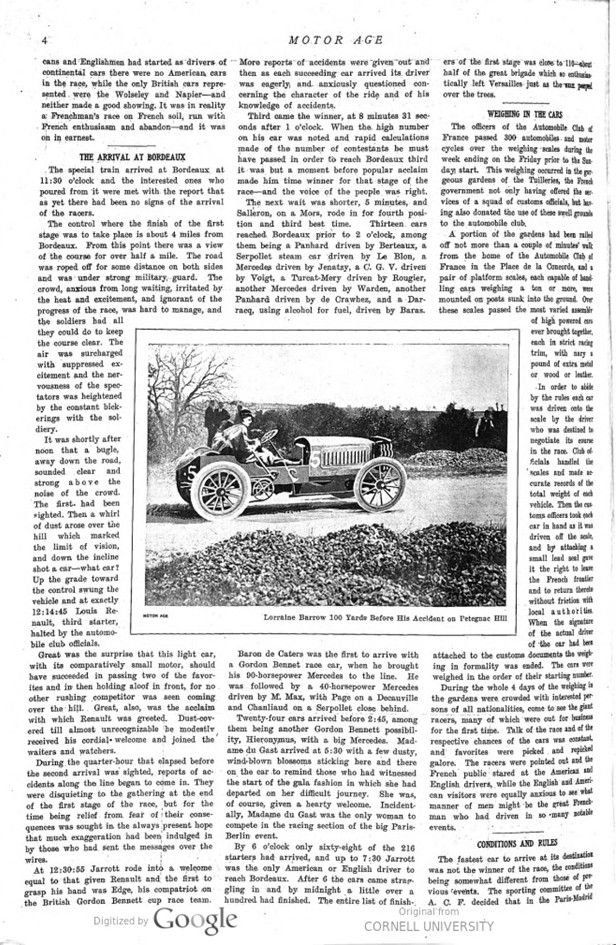

Page 4. Lorraine Barrow 100 Yards Before His Accident on Petegnac Hill

Page 5. AUTOMOBILE CLUB – The Official Ticket Box – Jarrott’s Arrival at Bordeaux – Edge Greets Him. – Arrival of Baras – Darracq – at Bordeaux.

6. A Cyclist Conducting a Racer Through a Neutral Control (Motor Age)

7. WEIGHING IN THE BIG RACERS FOR THE PARIS-MADRID

Lorraine Barrow on His de Dietrich – Vanderbilt on His Mors

Rene de Knyff on His Panhard. – Baron de Caters on His Gordon Bennett Mercedes

Sydney Girling’s English Wolseley – Jarrott’s Car Ready for the Scales – Jarrott in White Hat

For 4 days there was a constant stream of ungainly, uncouth racing cars rolling into the gardens of the Tuileries, where A. C. F. officials made accurate record of the weight of each car, and the custom officials attached the lead seals allowing them to leave the French frontier. The weighing-in scales were the center of attraction for thousands of visitors.