This interesting and analysing article compares not only opinions of the European automotive press, it also gives own results of interviews with some participants.

Text and jpegs by courtesy of hathitrust.org www.hathitrust.org, compiled by motorracinghistory.com

MOTOR AGE Vol. II, No. 4 – Chicago, July 24, 1902

LESSONS OF THE RACE FROM PARIS TO VIENNA

From a mass of interesting matter furnished by the European motor press the following facts and conclusions have been extracted, as bearing interestingly on the necessities of construction of vehicles combining speed with durability. The British press, particularly, is satisfied that the French makers sacrificed too much to speed, but for this, perhaps, some allowances should be made because of the success of the Napier in the cup race, that machine having been prepared with a view to stability rather than great speed.

If it is difficult, says the Autocar, to follow the incidents of a race in which nearly 150 vehicles are competing, it is still more puzzling to separate the wheat from the chaff in the crop of rumors that are constantly coming through. A competitor sees or hears something which he does not quite grasp during his rapid flight through the country, and imagination does the rest, transforming incidents into accidents, and accidents into catastrophes, until the spectators at the controls begin to think that the situation is getting serious. It stated positively that Gobron-Brillie car had been smashed up and the driver killed, but later on Madame Gobron, who was in the special train, declared that, though the driver was hurt, his in- juries were by no means serious. We saw a Peugeot on a railway truck at Bregenz, and a porter gave circumstantial details of how Caillois had been killed, but it turned out afterward that rumor had again proved a lying jade. As a matter of fact the only victim appears to have been Baron Henri de Rothchild’s driver, who was not racing at all.

And what about the Gordon Bennett cup? To tell the truth, no one seemed to have much doubt concerning the issue, and it was regarded as a foregone conclusion that with such a considerable advance upon the Napier the big Panhard had the trophy safely in hand. An accident was still possible, but hardly probable, when so near to the end of the journey. Then telegrams came in stating that ninety-five cars had left Bregenz, and that eighty-five had safely crossed the Arlberg. From Telfs there came a list of arrivals with the announcement that Chevalier Rene de Knyff had not been signaled. The French visitors began to get nervous. Other telegrams were eagerly scanned, but still there was no sign of M. de Knyff, and it was learned afterwards that his differential had broken when about twenty miles from Innsbruck. Meanwhile, Mr. Edge was still running, and the fear became a certainty when he was signaled as arriving at Innsbruck. The interest in the race was entirely forgotten in the discussion that was carried on over what the French regarded as a sort of calamity. The whole blame was laid on the Automobile Club de France for having chosen men instead of vehicles, and it was said to be highly imprudent to let the defenders drive new cars which had never been tested, and had not previously taken part in a race, and it was forgotten that the Napier was also untried. This discussion may be left to the French makers themselves, but it seems to be pretty clear that different arrangements will be carried out in the future, when the A. C. F. will select vehicles to challenge for the cup, instead of simply appointing men, who are allowed to drive what cars they please. The French will make tremendous efforts to get the cup back. One prominent maker informed us that it was a real disaster for the French industry, since it would mean the loss of a considerable amount of business, and when we pointed out that it was good for sport and would give additional interest to the race next year, he inquired if the race would be run off in England? This is the question which is most concerning the trade at the moment. Under the rules the cup must be run for in the country which holds it, and as racing is prohibited in England there must be one of two things, either get special permission to race for the cup in England or else modify the rules to allow of its being run for on the continent. Of course, the rules cannot be changed without the consent of the Automobile Club of Great Britain and Ireland, but there can naturally be no question that the club will do what it can to facilitate the organizing of a race abroad if it cannot possibly be done in England. Meanwhile, the French recognize that the success of the Napier will give an enormous stimulus to the English industry, and as the English makers will do their best to keep the trophy, it will mean a very keen struggle next year.

We interviewed Mr. Edge on his arrival in Salzburg, and he told a very exciting story of the run. In entering for the Gordon Bennett cup, he had little idea of winning the trophy, for, being so much lower powered than the French vehicles, he never expected to beat them in point of speed. He ran for the sake of getting experience and acquiring hints and ideas for improving the Napiers, so that they would eventually be able to show a decided superiority over the foreign cars. As he had won the cup because the other competitors had one by one broken down, we pointed out that this was of itself a proof of the superiority of the Napier under the special conditions of the race. If the French cars collapsed on the abominable Tyrol roads, and even on the course between Champigny and Belfort, it was because the makers had scarified all-round strength to engine power, and they knew very well that they were running a considerable risk. If they preferred to take this risk they had no one to blame but themselves. It was a battle between power and reliability, and as the latter quality came out victorious there can be no doubt that the best car won. Mr. Edge saw many a wreck by the wayside, and when he had left the Arlberg he passed a Peugeot smashed up, with the driver lying down looking very bad indeed.

Mr. Edge had little hope now of winning the cup. He passed Chevalier de Knyff in trouble, and asked him if the race was over, and, evidently misunderstanding the question, M. de Knyff answered in the affirmative.

The incidents of the race were pieced together afterwards from the stories of eyewitnesses, though a good deal of picturesque exaggeration had to be cut away to get at the true history of this marvelous ride. Baras, who was driving a Darracq with alcohol, related that another Darracq vehicle had fallen down a precipice for a distance of 800 feet without injuring the driver or his mechanism. This was perfectly true in a sense, but it was only half the truth. While descending the Arlberg the steering gear of the Darracq refused to act and the car ran off the road, and at the same time the cylindrical tank on which the Austrian driver, Max, was sitting broke away, throwing both men on to the road. The car dropped down the side, and was stopped by a ridge 100 feet below, while the tank went rattling and bounding to the bottom. Max let himself down to see the vehicle, which was an absolute wreck, and as he was climbing up Baras passed by, and was able to tell a wonderful story at the control. Still more wonderful was the feat accomplished by Louis Renault. He was at the Innsbruck control with four other cars wait ing for their turn to be sent off when Baron de Caters came up at full speed on his Mors, and in trying to pass in the narrow road broke the offside wheels of the Renault car. To most other competitors the case would have been hopeless, but M. Renault immediately set about repairing his wheels. He found some dry wood and cut out the spokes with a knife, making such a fine job of it that he was able to get to Vienna without trouble, and, had the spokes been painted, it would really have been difficult to see that a repair had been carried out at all.

The success of the Mercedes was the more remarkable as they were not built specially for the race, but were driven by private owners, and were of the same type as those which made their first appearance down at Nice. They were, of course, much lower powered than the big French vehicles, and it is no doubt on account of this that they did so well on the Tyrol roads. As the strength was not sacrificed to power to the same extent, they showed much greater resistance and got through to Salzburg without any trouble. The practical character of the car got the better of the theoretical application of high powers to the big French vehicles.

Altogether, the results of the race may be regarded as highly satisfactory, for about seventy vehicles and cycles succeeded in arriving in Vienna, or more than half the number starting from Champigny. This is a much higher proportion than could have been expected in view of the character of the Austrian roads, and shows that, though the new French powerful cars did less than was anticipated, they were by no means a failure, and the fact that the vehicles were able to come through such an ordeal proves that the French makers have accomplished a wonderful feat in building high-powered cars to resist such strains. The most conspicuous failures were the Gordon Bennett cup cars, which were put out of the race by the breaking of gears. At the same time the race has certainly shown that these high powers in lightly built carriages are a mis- take for bad roads, and, all things considered, the Mercedes did a better performance than the French vehicles, and they narrowly missed taking the two first places in the 1,000 kilogs. category, for Baron de Forest would have run the winner very close had he not lost a couple of hours on the first stage and broken his petrol tank near Vienna. The feature of the race, however, was the behavior of the light carriages. They showed up extremely well on the mountain roads, and, on the whole, ran with much greater regularity than the majority of the big cars.

The performance of the Renault was a revelation, and again classed it as the fastest and most reliable of its type. The motor is a four-cylinder engine of 16 nominal horsepower, but developing something like 22 horsepower. It is a new motor constructed by Renault Freres, who have put the usual conscientious work into it which is the great secret of their success. With the exception of one, which came to grief on the Arlberg, all the Darracqs covered the entire course in creditable times, and all four Serpollet vehicles reached Vienna, thus confirming the reliability which they showed in the Northern Alcohol Circuit. The Clements also performed satisfactorily, and the Gobron-Brillie-Nagants should not be overlooked, for, though making no pretense at high speed, they went over the whole course with great regularity. What this proportion of more than 50 per cent of successes means can only be appreciated by an inspection of the cars when they were put on exhibition in the Rotunde. There was scarcely one which had come out of the ordeal unscathed. They all wore a very battered look; some of them with the bonnets tied on with rope and others with parts of the carriage work smashed away and springs broken.

The mechanism must be of very solid construction to stand such strains. And yet while gears have broken we have not heard of a single instance of a motor failing, and the powerful Centaur engines on the Panhard cars do not seem to have given the slightest trouble. If these big vehicles did not break records on the Austrian roads, the experience in their construction has certainly not been lost, and it has resulted in the designing of much lighter and more efficient motors than would probably have been possible if makers had not set themselves the task of employing the maximum of power for the weight allotted to them. At the same time the French manufacturers have had enough of this kind of racing for the moment. It was more than they expected. They think that the test was not a fair one, and they are probably right, but almost before they have finished protesting that they will never race again in foreign countries they are talking of organizing the next race from Paris to St. Petersburg. Racing is such a big factor in the automobile industry that even those who calculate the huge expense and dread the fatigue and intense mental strain see that they cannot do without it.

French Say They Were Misled

Paris, July 10. – The prevailing opinions of Paris-Vienna in the French motor world, either sportive or industrial, seems to be that a huge misunderstanding was underlying the bottom of the whole affair. Paris-Vienna was advertised as a race pure and simple, and in a race speed is the essential factor of success. Paris- Vienna turned out an endurance test in the narrowest sense of the word, at least for three parts of it, and in such a test speed capacities counted for little, compared with robustness. The foreign competitors were fully aware of the fact, but not so with the French, whose vehicles were altogether too fast for the course and work. The slow pace rendered necessary by the condition of the roads, put a strain on their organs greater than would have done a higher rate of speed. No doubt they led in the end, but came very near losing to the Austrian brigade, for hadn’t Baron Zborowski made a mistake in Switzerland which forced the judge to penalize him, he would have been first in the most important class. The French were taken by surprise, so to speak. They never realized, except too late, what was in store for them, otherwise they would have placed different vehicles in the field. The lesson will serve them. They will make sure another time beforehand that the race whatever it is, answers the definitions of a race. On the whole the result must be voted highly satisfactory, since out of 137 cars that started on that terrific journey, eighty finished. That says much of the progress of the automobile all around.

German View of the Event

Although the Paris-Vienna race may now be considered an old story there is much talk about it in Europe. This especially is the case in Germany where the automobile papers vehemently denounced the Daimler-Mercedes concern for not having tried, in every possible way, to capture the event. One of the papers says: „The French victory should be a good lesson for our makers. We hope they will follow the process of our French neighbors by widely advertising their wares, by making an effort to break records, by sending their machines to other countries to compete, to open their eyes and see what others do in general, and by taking more interest in their goods with regard to the foreigner than they do at present. It is an erroneous idea to keep yourself closed up all the time and think that what the other fellow does or has is of no use to you. To think that two amateurs, one of whom had never taken part in a road race, while the other was very little better, finished among the first of such a long and hard race is pleasing and heart breaking at the same time, because we are of the opinion that, had the Daimler people entered this event like some of their French competitors there is no doubt that they would have finished in great style, for the simple reason that while on French roads the French machines might have held the lead, as they did, they certainly would not have been able to do so on the detestible roads of part of Switzerland and Austria, as these. German machines are built for the purpose of going through such rough country and are tested on them. The Daimler-Mercedes people probably do not care about what we say, for they have orders ahead for many years, but we think that they ought to have a little of that old and well known German patriotic spirit and seen to it that this event should have turned out as a German victory.“

Fotos.

One of the Dangers of the Paris-Vienna Route.

Renault, Shortly After His Arrival at Vienna.

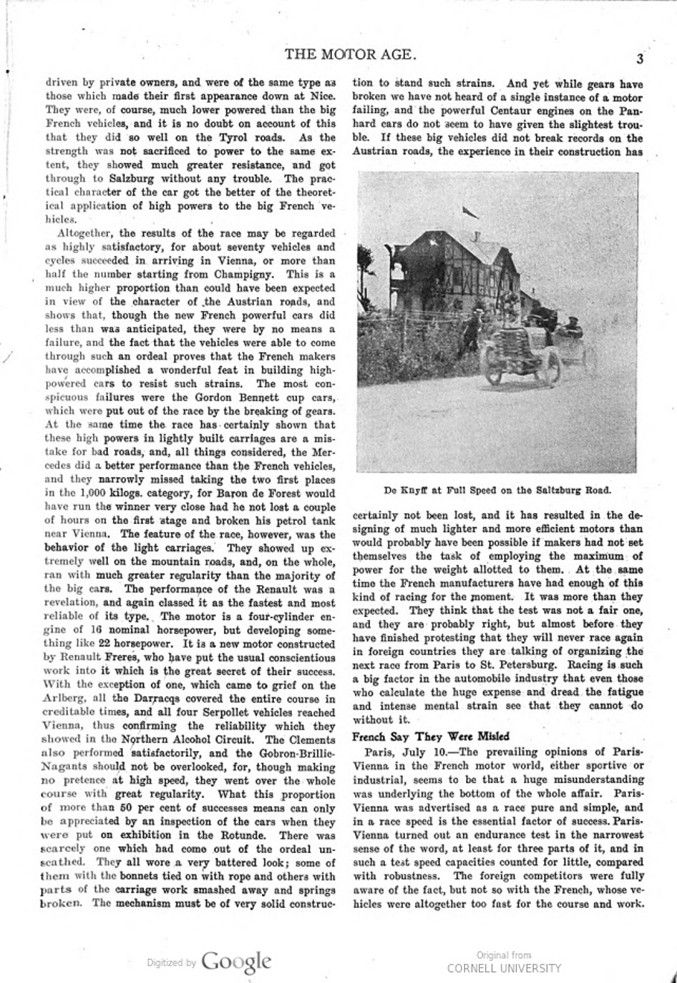

De Knyff at Full Speed on the Saltzburg Road.

EXTERIOR AND INTERIOR VIEWS OF MAURICE FARMAN’S GARAGE