Text and fotos by authorisation of Bibliothèque nationale de France – gallica.bnf.fr https://www.bnf.fr/fr

Translation by deepl.com

L’Auto, Vol. 22, No. 7.526, 24 july 1921, page 1

The Grand Prix of the Automobile Club of France

TOMORROW, MONDAY, ON THE CIRCUIT DE LA SARTHE

A 17.262-kilometer circuit to be completed 30 times, for a total of 517.860 kilometers. — First start at 9 a.m.

THE “THREE-LITER” WORLD CHAMPIONSHIP

The major international event, which will take place tomorrow on the Le Mans circuit, will pit British, American, and French specialists against each other in the engine formula created by l’Auto.

The history of the 1921 Grand Prix. — Advances in construction after seventeen years of racing. — Who are the competitors.

THE 1921 GRAND PRIX

Twelve cars at the start, one of which, Goux’s Ballot, has only a two-liter engine, as per the manufacturer’s wishes. I have heard some people say, “The field is weak.” What a mistake! Because it goes without saying that we are not interested in quantity alone, but in quality.

I don’t think we have ever had such a homogeneous field in any race. I firmly hope that all 12 cars at the start will be at the finish, with no more than a quarter of an hour between the first and last. I firmly believe that the outcome of the race will remain uncertain for a long time…

And above all, I regret the absolutely insufficient distance of 500 kilometers: the man who wins will not have a single pit stop or flat tire. That leaves too much to fate.

We will see later that all the manufacturers (even those who, although entered, will not start) have adopted the same solutions.

This is clear proof that the 3-liter rule has given all it can give and must be abandoned in the future.

But one might say, Indianapolis is keeping the 3 liters in 1922… All the more reason to change, so that next year the Grand Prix cars are not deflowered, and two competitors do not run away with it.

What should this new regulation be? I believe that we should make a clean break with all the old formulas, and I think that L’Auto will try something new in 1922.

But the A.C.F., which is more traditional, as is wise for such a group, will undoubtedly retain the essence of the formula by changing the coefficient, and under these conditions, I believe we will lean towards a maximum displacement of 2 liters and a minimum weight of between 720 and 750 kilos. I also believe that this would be a very good regulation for another two or three years.

By then, we will have seen the results of the regulations that L’Auto plans to introduce in 1922.

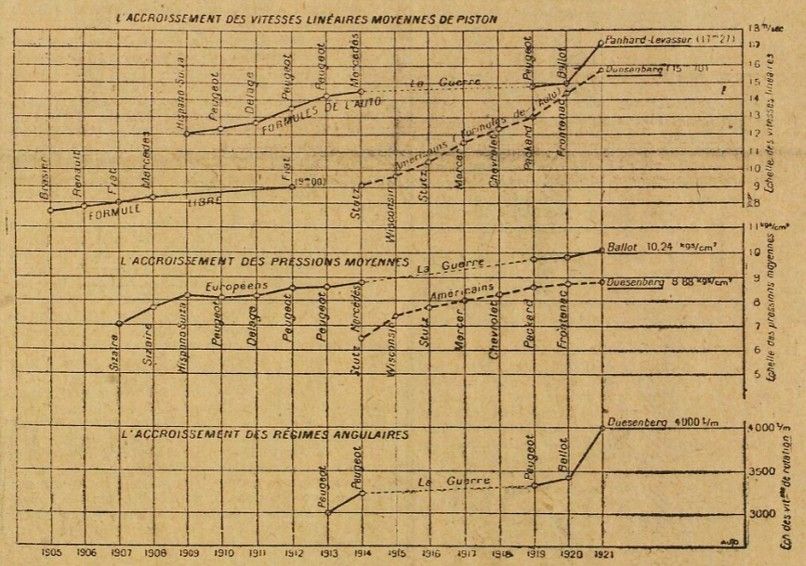

17 years of uninterrupted progress

We still sometimes meet — admittedly less and less often — excellent people who ask us seriously: “So, are you sure that racing serves a purpose? ….”

For those people, without much hope of convincing them, since misoneism and the denial of progress are clear evidence of intellectual poverty, for all those of the younger generations who need to know the history of a sport and the progress of an idea, I have drawn up the three graphs opposite, which summarize the mechanical achievements resulting from 17 years of public racing in Europe and America. For each year, we have taken the most qualified representative in terms of the specific point examined.

1. The increase in piston speeds

The great master Hugo Guldner said it in a lapidary way: The expansion must be short in time and long in space. It is therefore necessary to increase the average linear piston speeds.

Let N being the number of revolutions per minute of the engine at operating speed, L the value of the piston stroke in meters, the expression

N L / 30 gives the average linear piston speed in meters per second.

In 1905, with the famous Brasier of Auvergne, which was undoubtedly the best car of its time, we were at around 7 meters per second; seven years later, in 1912, with the Fiat de Dieppe, we were only at 9 meters per second. This slow and modest gain can be attributed to the fact that, during this entire period, we lived under the sole regime of the free formula, the most execrable of all in terms of engines. In fact, until 1907, only the weight limit of the chassis was considered, and this was work for the steel industry; the maximum fuel consumption (30 liters per 100 kilometers) and maximum bore (155 mm for a 4-cylinder engine) that came next were clearly exaggerated and did not lead to any progress.

Fortunately, it will be to our Auto’s credit that it understood the right path as early as 1906 and last year elicited the following valuable admission from the greatest American engineer, Mr. P. Heldt:

“Most of the usual ideas about engines were completely overturned by the results of the small car trials organized in France by the newspaper L’Auto… It was „first proven that efficiency was a function of stroke… then, the importance of high speeds was highlighted… “

And around the same time, the famous German engineer Riedier, head of the Charlottenburg test station, could exclaim:

”Thanks to the small engine tests organized by the French newspaper L’Auto, it can be said that a low-speed engine should be banned from automobiles and does not deserve to be called a modern engine… „

But what can you do? Prophets are rarely recognized in their own country, and I would like to share a personal memory here. In 190G, in a paper submitted to the Academy of Sciences, I demonstrated that, all other things being equal, the maximum power of an engine varies as the 0.6 power of the stroke. The following year, the Germans modified their tax formula accordingly, but, of course, it cannot be said that they copied a Frenchman, and they chose the exponent 0.5 for the stroke. My formula became the Brauer formula.

In 1912, five years later, the French mining department was also forced to adopt a fractional exponent. It chose neither 0.5 like the Germans, nor 0.6, the only exact exponent as I demonstrated, but 0.7, in order to have its own formula.

Let’s return to the l’Auto trials. From 1907 onwards, Sizaire-Naudin led the way with bold, richly designed engines, followed by the meteoric rise in our world of Marc Birkigt, who was to achieve such great mechanical success. With the 4-cylinder 65 bore engine of the famous 1909 Hispano, the piston speed jumped to 12 meters per second (the car did 125 km/h). From that moment on, there was a clear, noticeable difference between the Auto formula and the free formula. The diagram shows this clearly. We won, we won little by little until July 1914, and the big players were Peugeot, which must be mentioned several times, Delage, and Mercedes.

Then came the war. At that point, we had a clear advantage over American manufacturers, but for five years we had other concerns: look at the dotted line on the diagram representing the Americans and see how, because of the war, they gradually closed the gap on us.

They are going to catch up with us… they would have caught up with us if, two weeks ago, a phenomenon had not occurred at the Boulogne meeting. A Panhard-Levassor (driven by Rigal) runs at 3,700 rpm; the engine is an 82.5 x 140, so the average piston speed is 17.27 meters per second, a prodigious result, never before achieved, and one that will go down in the history of modern engine development.

Here, a parenthesis. This engine, with an average piston speed of over 17 meters per second, is a valveless Panhard-Knight. Thus, the valveless engine now holds four major records, which are as follows:

1° Record for the highest angular velocity: under load (5,000 rpm).

2. Record for lowest horsepower consumption (177 grams of gasoline at 710°).

3. Record for longest continuous operation under full load (336 hours at the A.C. Laboratory of America in December 1913 by a Moline-Knight), and finally, thanks to the oldest French brand.

4° Record for the highest average linear piston speed.

Hey, hey! That’s a nice track record for the valve-less engines.

2° The increase in average pressures

The diagram does not require much comment: as we can see, year after year, the efforts of the best manufacturers tend to feed their engine cylinders well and increase the average ordinate of the diagram.

With the same impartiality that we have always strived for, we would say that the prize in this very delicate competition goes to Ballot.

There seems to be something magical about him, as Ballot currently outstrips his most skilled rivals in this field. Others may be able to turn as fast as him, but no one knows how to make an engine breathe like him at all speeds. Let us hope, in the greater interest of science, that Ballot will one day reveal his secrets to us.

Consider that this year, Ballot will exceed 10 kilograms per square centimeter of average pressure. That’s fantastic!

3° The increase in angular speeds

I won’t dwell on this, because everyone is convinced today. The history of the progress of the internal combustion engine is intertwined with the history of the conquest of high rotational speeds.

On the Le Mans engine, Duesenberg reaches 4.000 rpm under load, and the power characteristic only drops after 4.200 rpm.

To be complete, I must mention a fourth criterion, which is the value of the engine torque in meter-kilograms per liter of displacement.

In 1905, we were at 4.5 m-kg per liter of displacement on the admirable Brasier; the 1906 Renault, winner of the first A.C.F. Grand Prix, rose to 4.9; the famous 1907 Fiat reached 5.3, and in 1908, the Mercedes reached 5.6; but that same year, with the Delage car that enabled Guyot to win the Grand Prix des Voiturettes, French construction, still in the lead, made a leap forward and rose to 6.1.

Since 1919, as a result of its mesmerizing power in terms of fueling a fast engine, Ballot has been clearly in the lead in an exciting battle; with its 1921 engines, it has reached the staggering rate of 7.5 m-kg per liter of displacement, giving a power output of (3 x 7.5 x 3,200) / 716 = approximately 100 horsepower at 3,200 rpm, and its power characteristic increases further after 3,600 rpm.

This is an engine that should end up in the Conservatoire des Arts et Métiers.

INCREASE IN AVERAGE LINEAR PISTON SPEEDS – scale of linear speeds [m/sec]

INCREASE IN AVERAGE PRESSURES – scale of mean pressures [kg/cm2]

INCREASE IN ANGULAR SPEEDS – scale of rotational speeds [rpm]

1905–1921 (diagram)

Lessons learned before the race

Generally speaking, it is necessary to wait until after a major race before being able to judge the new solutions that have been implemented.

This is not the case this year, as there was unanimous agreement on the choice of these solutions. The Fiats will not be racing, as they could not be ready in time, but even if they had been, they would not have been any different from the proposals we are about to list:

All competitors in the 1921 Grand Prix have:

1° An 8-cylinder in-line engine;

2. Hemispherical cylinder heads;

3. Overhead and multiple valves;

4. Streamlined shapes;

5. Wheels fitted with “Straight Side” tires.

Our readers are well aware that the first four points are “hobbies” that are dear to me, so I will spare them further commentary.

As for the adoption of American-style tires and inner tubes—Pirelli for Ballot, Barney Oldfield for Duesenberg, Dunlop for Talbot—this was determined by safety considerations. A flat tire does not come off the rim; even with a flat tire, you can drive at 130 km/h, and at Le Mans, we will have the curious spectacle of seeing the Duesenbergs leave without spare wheels. The test has been done several times; it takes less time to do a whole lap on a flat tire and change it at the refueling stop than to change it on the road and stop again at the refueling stop to pick up another wheel. This is a consequence of the small circuit.

Nevertheless, I still believe that tourists should prefer European-style beaded tires to American-style wire-bead tires. The future will tell.

Our predictions

I feel completely unable to choose between Ballot, Talbot, Talbot-Darracq, and Duesenberg, as luck plays such a big part in a race. Certainly, from a purely mechanical point of view, I have a preference for the former, who has once again made a considerable effort. The cars are very similar in terms of top speed, and both teams of drivers are made up of stars. Goux, with the small 2-liter Ballot, is terribly dangerous, despite its small engine size, and must take a place of honor.

Dare I say, despite all of de Palma’s talent, that I prefer the luck of Wagner and Chassagne to his; At Duesenberg, Guyot must be the favorite, but Joe Boyer, like Murphy, whom I have seen at work up close, are formidable “tinkers.” Finally, at Talbot-Darracq, André Boillot, Thomas, and Lee Guiness are first-rate drivers.

Still… still,

BALLOT MUST WIN

because he has four speeds (which counts at Pontlieue) and greater engine torque at operating speeds; the latter factor will count five to six times per lap; finally, our brilliant champion’s mechanical execution is flawless.

Really, Ballot must win… Everything is in his favor… The only feeling against him is superstition. This year, our sporting colors have been unlucky: we have lost in cycling, horse racing, aeronautics, boxing… but, bad luck aside, Ballot must win and will have richly deserved it.

The average speed, you may ask? I believe the winner will finish in between 4:10 a.m. 10 and 4:20, if the weather is good, or an average of 120 to 123 kilometers per hour. However, I expect a lap to be covered in 7 minutes and 40 seconds, which would make the average speed for that lap over 135 kilometers per hour.

Ch. Faroux.

Times, order of departure, and numbers

9:00 00 s. — 1. Ballot I (Ralph de Palma).

— 2. -Sunbeam I (forfeit).

9:00 30 s. — 3. Mathis I (X….).

— 4. Talbot 1 (Lee Guiness).

9:01:00 — 5. Talbot-Darracq I (R. Thomas)

— 6. Duesenberg 1 (Albert Guyot).

9:01:30 — 7. Fiat I (withdrew).

— 8. Ballot II (Chassagne).

9:02:00 — 9. Sunbeam II (did not finish).

— 10. Talbot II (Seegraves).

9:02:30 — 11. Talbot-Darraeq II (A. Boillot).

— 12. Duesenberg II (J. Murphy).

9:03:00 — 13. Fiat II (did not start).

— 14. Ballot III (Wagner).

9:03:30 — 15. Talbot-Darracq III (Zborowski).

— 16. Duesenberg III (Joe Boyer).

9:04:00 — 17. Fiat III (did not start).

— 18. Ballot IV (J. Goux).

9:01:30 — 19. Duesenberg (A. Dubonnet).

THE LAST “CANTER”

(From our special correspondents)

Le Mans, July 23 (by dispatch). — Due to the circumstances that caused the Talbot and Talbot-Darracq teams to arrive late at Le Mans, the Sports Commission authorized a final day of testing this morning, Saturday, between 4 and 6 a.m., with the roads carefully guarded, as usual, by members of the A.C.O., whose dedication was once again evident.

So, this morning, we saw André Boillot and Thomas at work in the Talbot-Darracq, as well as Lee Guiness and Seagraves in the Talbot. The morning was particularly busy, with the four Duesenbergs also taking advantage of the opportunity to practice.

At Talbot, as at Talbot-Darracq, it was the first time the men had been on the circuit, and it is understandable that none of them pushed themselves to the limit.

At Duesenberg, Dubonnet was an exception, as he got his car very late and was forced to make adjustments. Joe Boyer and Guyot performed well, with Guyot making an excellent impression with his smooth, fast cornering, which did not strain the car.

Murphy breaks lap record in practice

But the honors on this last day of practice went to Jimmy Murphy, who completed five laps, the last three in a total time of 23 minutes 23 seconds, with the following respective times: 7 minutes 55 for the first, 7 minutes 47 for the second, and 7 minutes 40 for the third. In the stands, a stopwatch even recorded 7 minutes 38 seconds for the last lap.

These findings speak for themselves. As I have always believed, we will see a fierce battle in the Grand Prix. Let’s add that Murphy is still feeling the effects of his crash, that the day before yesterday he was unable to drive and that yesterday he said he was unsure whether he would be able to start. I saw the American driver this morning after practice. He had had to literally armor himself to be able to withstand the jolts and was showing signs of fatigue.

— “I think I can go a little faster,” he told me.

And next to him, Joe Boyer smiled confidently.

We’ll have laps in 7 minutes 30 seconds, believe me, at an average speed of over 138. And we don’t yet know everything the Ballots have up their sleeves!

C. Faroux.