The 1912 Grand Prix de l’Automobile Club de France this year ran on the triangular course of Dieppe, near to the North Sea. This article in La Vie Automobile, written by Charles Faroux, will be posted in two separate parts. The complete article covers their eintire race report. In this second part,the defeated, as they are called, the cars that did not fare well in the race, are highlighted.

Avec l’autorisation du Conservatoire numérique des Arts et Métiers (Cnum) – https://cnum.cnam.fr

Texte et photos compilé par motorracinghistory.com

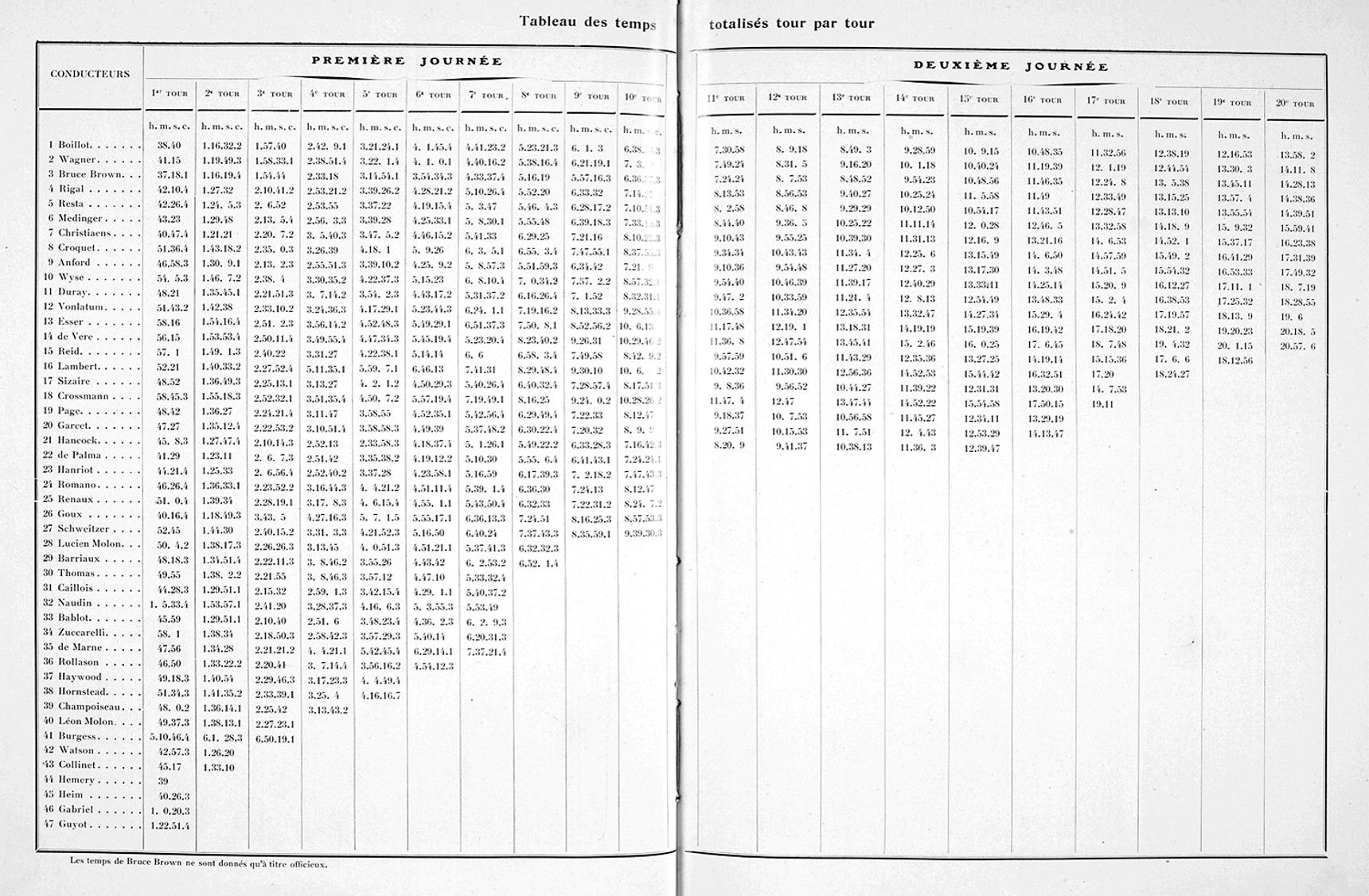

LA VIE AUTOMOBILE 12e Année. — N° 562. – 6 Juillet 1912, page 423 – 430.

LES VAINCUS

D’abord, en première ligne, Fiat. Mérite-t-il bien ce nom ? Il est des défaites glorieuses comme des victoires, et celles de Fiat paraît être de celles-là. Ses voitures étaient de tous points admirables et ont marché splendidement. Bruce Brown, qui a terminé en tète, la première journée, n’a été arrêté la seconde que par la panne la plus stupide qui soit : la panne d’essence. Il a dû se ravitailler en cours de route et a été disqualifié de ce fait. La même male-chance a mis hors de course l’autre Fiat, celle de de Palma, et la Peugeot de Goux. Voici trois des meilleurs combattants éliminés pour une cause insignifiante ; le règlement sera à modifier sur ce point.

Les Fiat étaient en outre handicapées par leurs roues en bois, je l’ai dit, et par leur faible empattement. Pour ces deux causes, leur consommation de pneus fut plus grande que celle des Peugeot et leur tenue de route intérieure. Mais leur course fut des plus belles et sans aucun ennui mécanique.

Si les deux journées avaient constitué deux courses distinctes, nos lecteurs le savent, Fiat les gagnait toutes deux. II est inutile de rien ajouter à cette constatation.

L’Excelsior de Christiaens fit une course absolument remarquable. C’est la première fois qu’un six cylindres se classe aussi brillamment dans une grande épreuve, et il est probable que sans les démêlés que son conducteur eut avec son embrayage qui patinait, elle se serait classée mieux encore. Ceci est tout à l’honneur de Bosch et de Zénith qui en assuraient l’allumage et l’alimentation, car on peut se figurer combien ces fonctions sont [délicates à bien remplir sur un six cylindres tournant aux vitesses angulaires usitées en course.

Le premier de nos représentants est Schneider, dont la voiture, conduite par Croquet, arrive 7e. Cette performance est d’autant plus remarquable que le sans-soupape 80 x 149 n’ayant pas été prêt à temps, ses voitures ont couru avec un simple 82,5 x 140 de série, un peu plus poussé, qui ne fait guère que deux litres et demi. Le résultat obtenu est tout à fait remarquable.

Les Rolland-Pilain ont eu une male-chance persistante, que, certes, elles ne méritaient pas. Celle de Guyot, après des ennuis de magnéto qui allumait deux cylindres à la fois et a mis le feu à son carburateur, a été arrêtée par un coussinet de tète de bielle fondue. Celle d’Anford, après avoir tourné magnifiquement la première journée, refuse de partir la seconde, ayant ses bougies encrassées. Dans un démontage hâtif, il croise les fils d’allumage et ne peut partir. Pilain, venu jeter un coup d’œil, trouve le mal ; mais il a touché à la voiture, il doit, aux termes du règle ment, être son conducteur. Il ne connaît pas la route, n’a pas conduit en course depuis longtemps, n’importe, il part et amène au poteau sa voiture, une 40 HP de série à peine poussée, qui se classe quatrième de la catégorie formule libre. N’est-ce pas une démonstration de la grande valeur de ces châssis ?

Alcyon, sans quelques ennuis, aurait certainement inquiété Sunbeam ; malheureusement un de ses meilleurs conducteurs, Page, se retourne au pont d’Ancourt.

Bien de grave d’ailleurs. Une de ses voitures, conduite par Duray, ai rive au poteau.

Devant elle se place une Arrol-Johnston, conduite par Wyse, qui a fait une course très régulière.

Il en est de même de Vinot-Deguingand, dont la voiture peu rapide, ne visait pas la première place et ne tendait qu’à faire une démonstration de régularité.

Elle l’a faite, pleinement convaincante.

Côte également, et l’intérêt de sa performance se double de ce qu’elle est exécutée par un moteur à deux temps. Disons tout de suite que les deux moteurs ont admirablement marché, sans un ennui, et que les deux voitures se seraient retrouvées à l’arrivée si Gabriel n’avait pas été lâché par son pont arrière.

La Mathis de trois litres n’étant pas prête, Esser a pris le départ avec une petite 70 x 120 qui, avec deux hommes, a tourné inlassablement à 75 de moyenne et a terminé sans un accroc les 1.540 kilomètres.

Qu’en dites-vous ?

Restent maintenant les malchanceux, ceux qui ont abandonné la lutte. En première ligne vient Lorraine-Diétrich. Voilà des voitures qui étaient prêtes et avaient fait leurs preuves à Sillé-le-Guillaume ; jamais le moteur n’avait donné d’ennui. Or trois d’entre elles ont été trahies par des ressorts de soupapes, la quatrième, a été retirée de la lutte. L’excellente firme d’Argenteuil aura certainement sa revanche.

L’équipe Sizaire et Naudin a aussi été poursuivie par la guigne.

Le bris d’un roulement à billes a arrêté Naudin, Schweitzer a été victime d’un graissage excessif et Sizaire a eu des ennuis d’allumage.

De même la Lion-Peugeot de Thomas qui, paraît-il, a changé cinquante-six fois de bougies !

Grégoire, à la suite de l’accident de Collinet qui a coûté la vie à son mécanicien Bassaguana, a abandonné.

On ne peut qu’approuver le sentiment qui a dicté cette décision.

Disons, pour terminer, quelques mots de la roue métallique Sankey qui équipait les voitures Sunbeam.

Cette curieuse roue, qui présente l’aspect de la roue en bois, est formée de deux parties en tôle d’acier emboutie, et soudées à l’autogène, la soudure étant dans le plan médian de la roue.

L’épreuve qu’elles viennent de subir a prouvé leurs qualités.

Un mot encore des organes accessoires. Parmi eux il en est un qui assure une importante fonction, c’est le radiateur. Combien d’excellentes voitures arrêtées parce que leur moteur chauffait, ou que le radiateur fuyait P Qu’on se souvienne de Lancia en Auvergne. Pour être tranquille de ce côté, Peugeot avait muni ses voitures du célèbre Arécal de Grouvelle et Arquembourg, tant de fois victorieuses déjà et qui équipe ses voitures de tourisme. Ce lut une victoire de plus.

Et puisque j’ai parlé de Bosch, je dois dire que si sa magnéto équipait tous les concurrents, ses bougies étaient sur bon nombre de voitures, bit celles-là n’eurent pas à s’en plaindre.

Et maintenant, à l’œuvre pour le Grand Prix de 1913.

C. Faroux.

Légendes des images.

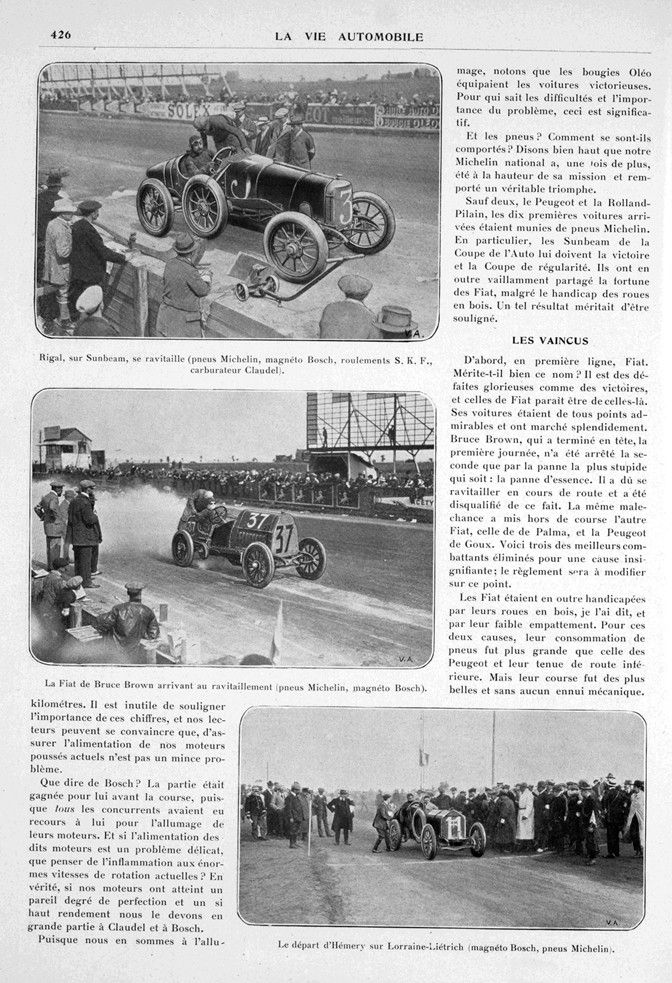

Page 426.

Rigal, sur Sunbeam, se ravitaille (pneus Michelin, magnéto Bosch, roulements S. K. F., carburateur Claudel).

La Fiat de Bruce Brown arrivant au ravitaillement (pneus Michelin, magnéto Bosch).

Le départ d’Hémery sur Lorraine-Diétrich (magnéto Bosch, pneus Michelin)

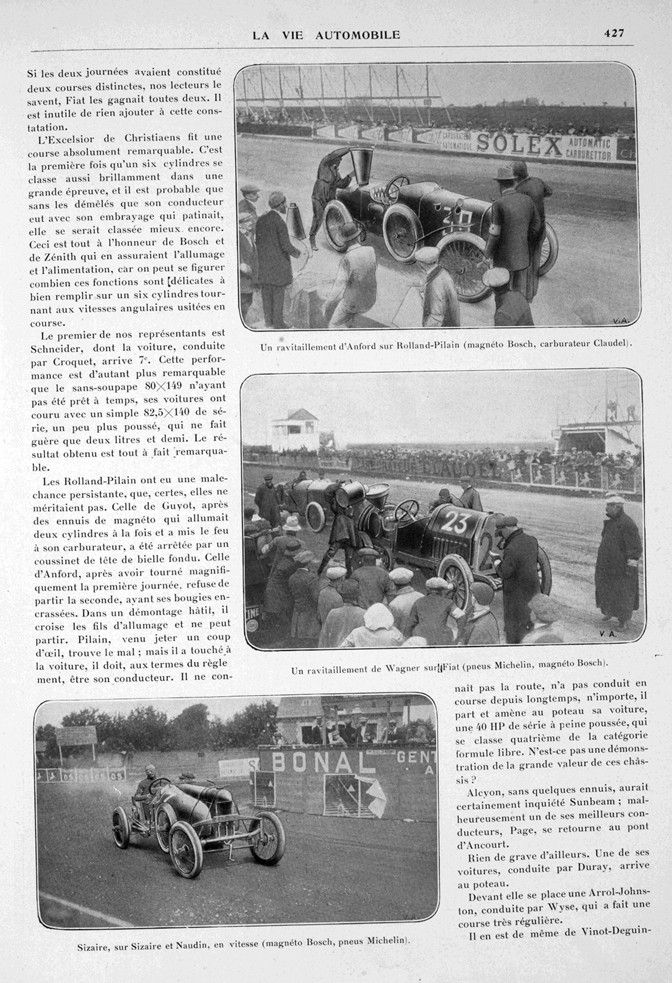

Page 427.

Un ravitaillement d’Anford sur Rolland-Pilain (magnéto Bosch, carburateur Claudel).

Un ravitaillement de Wagner surJjFiat (pneus Michelin, magnéto Bosch).

Sizaire, sur Sizaire et Naudin, en vitesse (magnéto Bosch, pneus Michelin).

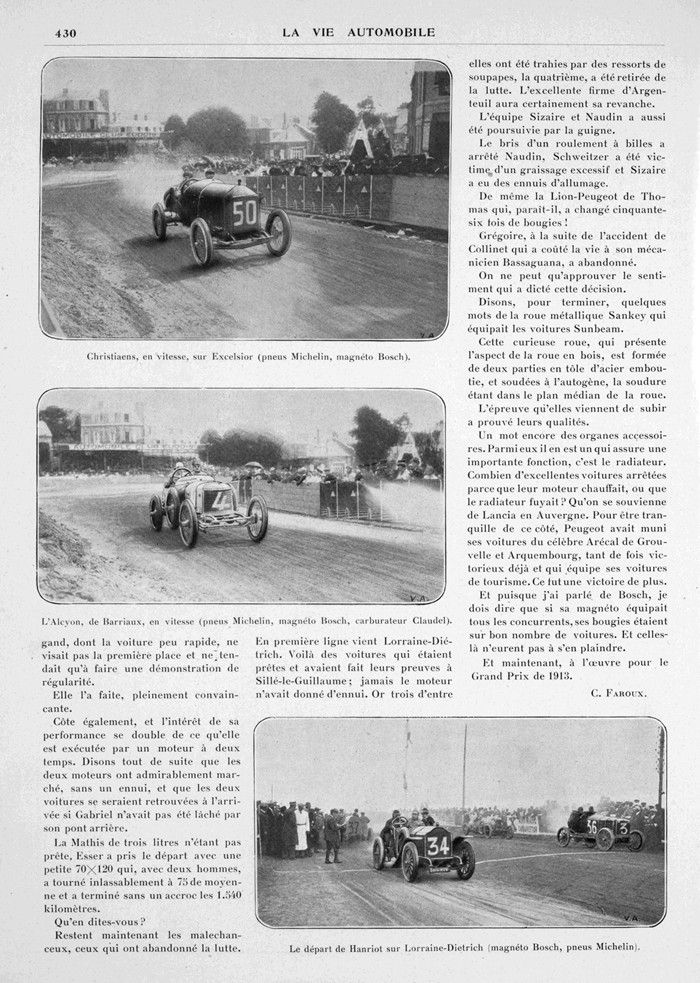

Page 428.

Christiaens, en vitesse, sur Excelsior (pneus Michelin, magnéto Bosch).

L’Alcvon, de Barriaux, en vitesse (pneus Michelin, magnéto Bosch, carburateur Claudel).

Le départ de Hanriot sur Lorraine-Dietrich (magnéto Bosch, pneus Michelin).

Agence Rol, gallica.bnf.fr

Agence Meurisse, gallica.bnf.fr

Translation by DeepL.com deepl.com

The A.C.F. Grand Prix and the Cup l’AUTO, 2.

THE DEFEATED

First and foremost, Fiat. Does it deserve this name? There are defeats as glorious as victories, and Fiat’s seems to be one of them. Its cars were admirable in every way and performed splendidly. Bruce Brown, who finished in the lead on the first day, was only stopped on the second day by the most stupid breakdown imaginable: running out of gas. He had to refuel en route and was disqualified as a result. The same bad luck put the other Fiat, driven by de Palma, and the Peugeot driven by Goux out of the race. Here were three of the best competitors eliminated for a trivial reason; the rules will have to be changed on this point.

The Fiats were also handicapped by their wooden wheels, as I have said, and by their short wheelbase. For these two reasons, they used more tires than the Peugeots and had poorer handling. But they drove a superb race and had no mechanical problems whatsoever.

If the two days had been two separate races, as our readers know, Fiat would have won both. There is no need to add anything to this observation.

Christiaens‘ Excelsior had an absolutely remarkable race. This is the first time that a six-cylinder car has performed so brilliantly in a major event, and it is likely that without the problems its driver had with his slipping clutch, it would have finished even higher up the rankings. This is a credit to Bosch and Zenith, who provided the ignition and fuel supply, as one can imagine how delicate these functions are on a six-cylinder engine running at the angular speeds used in racing.

The first of our representatives is Schneider, whose car, driven by Croquet, finished seventh. This performance is all the more remarkable given that the 80 x 149 valveless engine was not ready in time, so his cars raced with a standard 82.5 x 140, which is slightly more powerful but only has a capacity of two and a half liters. The result achieved was quite remarkable.

The Rolland-Pilains had persistent bad luck, which they certainly did not deserve. Guyot’s car, after problems with the magneto, which fired two cylinders at once and set his carburetor on fire, was stopped by a melted connecting rod bearing. Anford’s car, after running magnificently on the first day, refused to start on the second, its spark plugs being fouled. In a hasty dismantling, he crossed the ignition wires and was unable to start. Pilain, who came to take a look, found the fault, but as he had touched the car, he had to be the driver according to the rules. He didn’t know the road and hadn’t driven in a race for a long time, but he didn’t care. He set off and brought his car, a standard 40 HP with hardly any tuning, to the finish line, where it came fourth in the open class. Was this not a demonstration of the great value of these chassis?

Alcyon, without a few problems, would certainly have worried Sunbeam; unfortunately, one of its best drivers, Page, spun out at the Ancourt bridge.

Quite serious, in fact. One of its cars, driven by Duray, ended up at the post.

In front of it was an Arrol-Johnston, driven by Wyse, who had driven a very consistent race.

The same was true of Vinot-Deguingand, whose car was not very fast and was not aiming for first place, but only wanted to demonstrate its consistency.

It did so and was thoroughly convincing. Côte also performed well, and the interest of his performance is doubled by the fact that it was achieved with a two-stroke engine. Let us say straight away that both engines ran admirably, without a hitch, and that both cars would have finished together if Gabriel had not been let down by his rear axle.

As the three-liter Mathis was not ready, Esser took the start with a small 70 x 120 which, with two men, ran tirelessly at an average speed of 75 and completed the 1,540 kilometers without a hitch.

What do you think?

Now we come to the unlucky ones, those who gave up the fight. First in line is Lorraine-Diétrich. These were cars that were ready and had proven themselves at Sillé-le-Guillaume; the engine had never given any trouble. However, three of them were let down by valve springs, and the fourth was withdrawn from the race. The excellent Argenteuil firm will certainly have its revenge.

The Sizaire and Naudin team was also dogged by bad luck.

A broken ball bearing stopped Naudin, Schweitzer was the victim of excessive lubrication, and Sizaire had ignition problems.

Similarly, Thomas’s Lion-Peugeot apparently had its spark plugs changed fifty-six times!

Grégoire withdrew following Collinet’s accident, which claimed the life of his mechanic Bassaguana.

One can only agree with the sentiment behind this decision.

Finally, a few words about the Sankey metal wheel fitted to the Sunbeam cars.

This curious wheel, which looks like a wooden wheel, is made of two pressed steel parts welded together using autogenous welding, with the weld in the middle of the wheel.

The test they have just undergone has proven their quality.

A word about the accessories. Among them is one that performs an important function: the radiator. How many excellent cars have been stopped because their engine overheated or their radiator leaked? Remember Lancia in Auvergne. To be on the safe side, Peugeot had equipped its cars with the famous Arécal de Grouvelle et Arquembourg, which had already been victorious many times and was used in its passenger cars. This was yet another victory.

And since I mentioned Bosch, I should say that while its magneto was fitted to all the competitors‘ cars, its spark plugs were used in many of them, and there were no complaints about them.

And now, let’s get to work for the 1913 Grand Prix.

C. Faroux.

Image captions.

Page 426

Rigal, in a Sunbeam, refuels (Michelin tires, Bosch magneto, S. K. F. bearings, Claudel carburetor).

Bruce Brown’s Fiat arriving at the refueling station (Michelin tires, Bosch magneto).

Hémery’s departure in a Lorraine-Diétrich (Bosch magneto, Michelin tires).

Page 427.

Anford refueling in a Rolland-Pilain (Bosch magneto, Claudel carburetor).

Refueling for Wagner in a JjFiat (Michelin tires, Bosch magneto).

Sizaire, in a Sizaire et Naudin, speeding (Bosch magneto, Michelin tires).

Page 428.

Christiaens, speeding in an Excelsior (Michelin tires, Bosch magneto).

L’Alcvon, driven by Barriaux, speeding (Michelin tires, Bosch magneto, Claudel carburetor). Hanriot’s departure in a Lorraine-Dietrich (Bosch magneto, Michelin tires).