One day after the 1921 French Grand Prix on the la Sarthe road course, the daily magazine or newspaper l’Auto published an extended report on the race. Again, written by none other than Charles Faroux. Here the first part of that report (translated by DeepL.com) in the Tuesday 26th July issue of L’Auto.

Text and jpegs authorised by the Bibliothèque national francais, gallica.bnf.fr www.gallica.bnf.fr compiled by motorracinghistory.com – Translation by DeepL.com

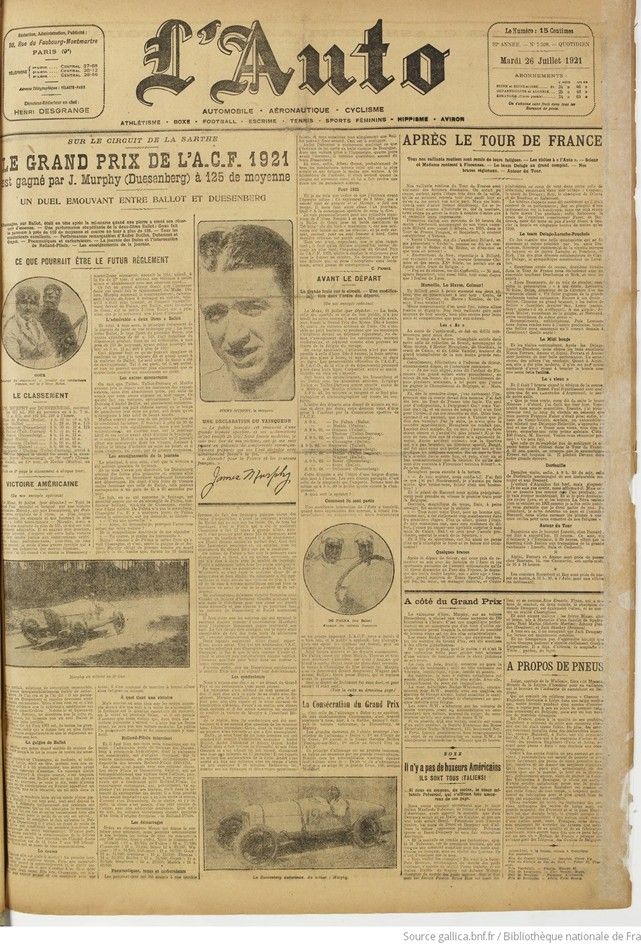

L’Auto, Vol. 22, No. 7.528, Tuesday july 26 1921 – Part 1.

ON THE CIRCUIT DE LA SARTHE

THE 1921 A.C.F. GRAND PRIX

is won by J. Murphy (Duesenberg) at an average speed of 125 km/h.

AN EXCITING DUEL BETWEEN BALLOT AND DUESENBERG

Chassagne, driving a Ballot, was in the lead halfway through the race when a stone punctured his fuel tank. — An astonishing performance by the two-liter Ballot: Goux completed the course at an average speed of nearly 110 and covered one lap at over 126. — All the drivers were excellent. — Remarkable performances by André Boillot, Dubonnet, and Guyot. — Tires and carburetors. — The day of the brakes and the intervention of Rollad-Pilain. — Lessons learned from the day.

WHAT THE FUTURE REGULATIONS COULD BE

THE RANKINGS

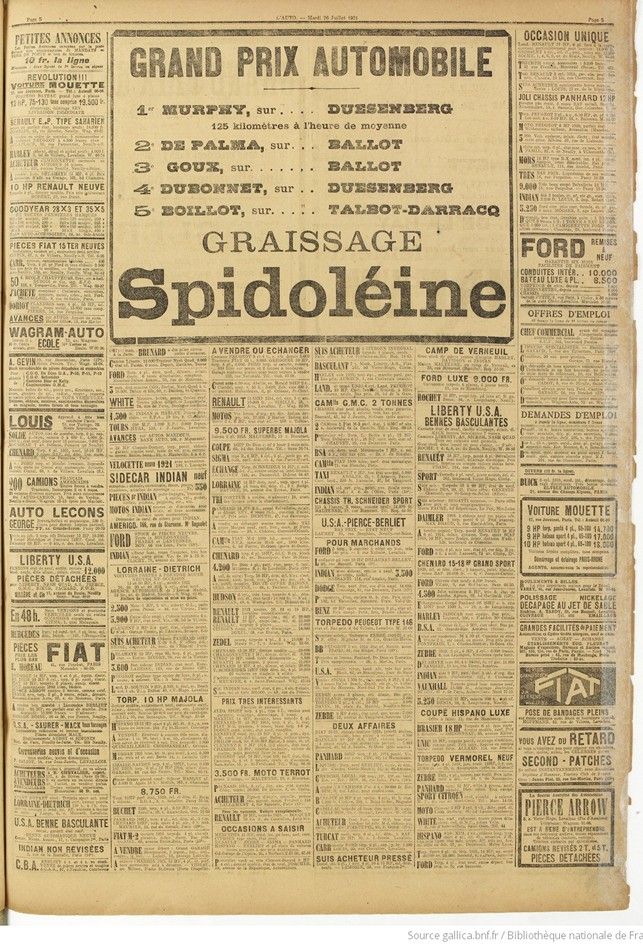

1. JIM. MURPHY in a DUESENBERG, covering the 517.860 km course in 4 hrs. 7 min. 11 sec. 2/5, or 125.702 km/h.

2. Ralph de Palma (Ballot). 4 hrs. 22 min. 08 sec. 1/5

3. Goux (Ballot) 4 hrs. 28 min. 38 sec. 1/5

4. A. Dubonnet (Duesenberg) 4 hrs. 30 mins. 19 secs. 1/5

5. A. Boillot (Talbot-Darracq) 4 hrs. 5 mins. 47 secs.

6. A. Guyot (Duesenberg) 4 hrs. 43 mins. 13 secs.

7. Wagner (Ballot) 4 hrs. 48 mins. 01 sec.

8. Lee Guiness (Talbot) 5 hrs. 06 mins. 43 sec.

9. Seegraves (Talbot) 5 hrs. 08 mins. 06 sec.

Not placed: Thomas (Talbot-Darracq), stopped on the 13th lap (when the circuit was reopened to traffic); Boyer (Duesenberg), on the 18th lap; Chassagne (Ballot), on the 17th lap, and Matins (Mathis), on the 16th lap.

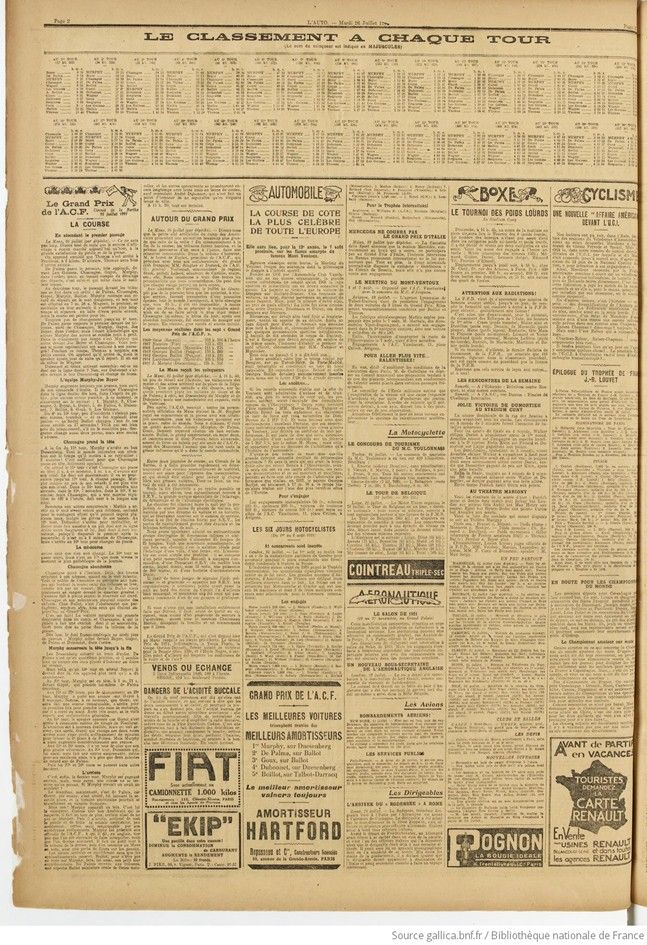

(See page 2 for the rankings at each lap).

AMERICAN VICTORY (From our special correspondents)

Le Mans, July 25 (by dispatch). — The Grand Prix is over, ending with a decisive victory. Murphy, driving a Duesenberg, which had the longest race among the entrants with its 3-liter engine and was the fastest — at 4,000 revolutions per minute — Murphy, therefore, won at an average speed of over 125, which is simply admirable. In all fairness, there can be no question of quibbling over this fine victory, and justice must be done to the American manufacturers. Thus, we will perhaps continue to bear the burden of a terrible war that has diverted our industries from fruitful endeavors for a long time to come.

I told you when I studied the Duesenberg: perfect design, impeccable engineering solutions, but some parts seemed incredibly weak. I believed it and I said it: it seemed to me that these fast Duesenbergs would have mechanical problems. They had none, and this is clear proof that the American steel industry is making considerable progress. Let’s take note of this and use it to our advantage. Above all, let’s not abandon the fight, and above all, let’s not leave Ballot alone to bear the burden of this terrible struggle.

Finally, of all the major races, the 1921 Grand Prix was the one with the lowest dropout rate, further proof that the current regulations have achieved their goal.

Ballot’s bad luck

It seems that our great master of the engine will have to drink the cup of bitterness till there’s no more.

Our driver Chassagne, so modest, so deserving, so skilled, was in the lead, carrying all our hopes, when he had to abandon the race because a stone punctured his gas tank. This bad luck is merciless! In every race, it is always through some minor mishap that Ballot loses what should be his, and yet, I tell you, we have never had a manufacturer in France who brings such enthusiasm, such tenacity, such care in preparation.

And then, I would like to do full justice to Ballot: he has been all alone since the war, valiantly defending our colors on all fronts. Let us show him the gratitude he deserves and recognize that fate alone bears the weight of what has happened.

It should be noted that there was a weight difference of 150 (?) kilos between the Ballot and the Duesenberg, which was a significant handicap to our representative. On the other hand, we checked the fuel consumption of Goux’s 2-liter car, which, of course, had a Claudel engine. Its fuel consumption is 14.2 liters per 100 kilometers. That speaks for itself.

The race

How easy it is to describe! On the first lap, Boyer set the fastest time. Then his teammate Murphy took the lead and held it until the 11th lap, when he had to stop for 2 minutes and 15 seconds to change two wheels. From then on, Chassagne, who had not yet pushed himself and was driving with wonderful consistency, took the lead when, at the end of the 17th lap, he arrived at the grandstands at a slow pace and retired with a punctured fuel tank…

There was a great, desolate silence among the huge crowd that had made the trip to Le Mans. From then on, Murphy took the lead, slowing down to preserve his car, since he was no longer being challenged, and finished comfortably ahead of de Palma in the Ballot, followed by Goux in the small 2-liter Ballot, which, as I had predicted, took a place of honor.

The admirable “two-liter” Ballot

And here, in my opinion, is the main event of the day from a purely technical point of view: the two-liter Ballot, the Sport model for the upcoming Motor Show, a four-cylinder 69 x 120, finished third in the overall standings, in a formidable field, at an average speed of almost 110, even completing a lap in 8 m. 13 s, or more than 126!

This exceeds anything we could have imagined and confirms what I have always said and thought about Ballot’s mastery. Goux’s only stop was to refuel. He left as he arrived, and nothing could show more clearly that this wonderful model is absolutely perfect.

The other competitors

We know that Talbot, Talbot-Darracq, and Mathis started the race at the insistence of the organizers, without being completely ready, due to the concerns we outlined at the time. What these cars achieved, especially André Boillot’s Talbot-Darracq, is absolutely remarkable, and once these beautiful chassis have had time to be fine-tuned, there is no doubt that they will go on to achieve great success.

Mathis raced one of his small cars and drove it himself. He averaged nearly 90 mph and was very consistent, but stopped voluntarily on the sixth lap because the hasty installation of his front brakes had reduced the steering angle, and the courteous Mathis felt that he might hinder his competitors in the corners. Give Mathis time to finish his setup, and he too will surprise us with high averages.

Lessons learned today

In my opinion, the main thing is that the victory was mainly a question of braking.

I made no secret of the fact that the Duesenbergs had more powerful brakes and, as they were light, they also had an advantage when starting. Despite a gearbox that was not as good as Ballot’s, this could correspond to a gain of 15 to 20 seconds per lap.

The fact, as far as braking is concerned, is further accentuated by what de Palma, a brilliant driver, achieves compared to Chassagne, a driver of equal merit. De Palma does not have power brakes. Chassagne does. A few days ago, de Palma tried the power brakes at my request and said: “It’s wonderful!”

“So why did you refuse to have it on your car?” I asked him.

The friendly American replied: “In racing, I’m wary of new things.”

Alas! Give de Palma the same brakes as Chassagne had, and after the latter’s bad luck, Murphy is forced to push like a madman until the end, while during the last 13 laps, he is content to drive at a good pace without tiring his car.

What makes a victory

But as we can clearly see that the times predicted ten years ago are about to come to pass: braking is the key issue at the moment, as we will see at the next Motor Show, and we can safely say that any car that, in two years‘ time—a powerful car, that is—does not have front brakes will not be a modern car. The public has fully understood this, and manufacturers are coming round to it.

Rolland-Pilain intervenes

And we must console ourselves on one point: the admirable braking system of the Duesenbergs, with its hydraulic control and considerable power, is of French origin. The American car incorporates all the features of the Rolland-Pilain patents of 1910-1911.

The matter was handled with the utmost fairness between Pilain and Duesenberg. The latter, who is probably the victim in this case, currently pays a license fee to an American group that coldly plundered Rolland-Pilain. The Tours-based manufacturer, which will be applying its patents next year, needed to safeguard its rights; so he proceeded with a descriptive seizure after the race, in agreement with Duesenberg. I repeat, and I insist, the matter was handled with admirable courtesy on both sides. In any case, the winning cars were equipped with a French-made brake: the Rolland-Pilain.

The starts

Thanks to the Morge stopwatch, which is accurate to one hundredth of a second, we can provide our readers with the times of all the competitors over 200 meters from a standing start. Here is the ranking:

Murphy: 12.61 seconds; de Palma: 12.77 seconds; Chassagne: 12.79 seconds; Boyer: 12.83 seconds; Wagner: 12.84 seconds; Dubonnet: 12.94 seconds; Goux: 13.11 seconds; Guinness: 13 s. 21/100; Thomas: 13 8. 34/100; Boillot 13 s. 71/100; Guyot: 15 s. 24/100; Seegraves: 14 s. 29/100; Mathis: 16 s. 03/100.

Tires, wheels, and carburetors

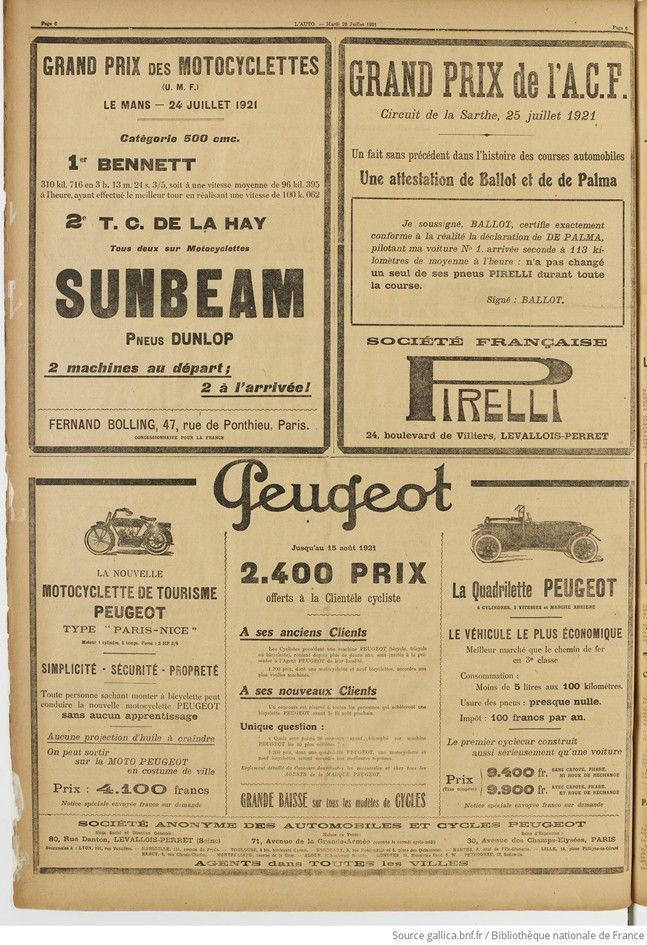

The tires were put to a terrible test due to the braking, as none of today’s brakes had the valuable advantage of the Ballot, which does not lock the wheels. Of all the tires, Pirelli performed the best. Chassagne completed 17 laps at high speed, leading the race with an average speed of nearly 125 km/h, without changing a tire, and when he had to retire, his Pirelli tires were still in perfect condition. This should be widely publicized, and what’s more, all the Grand Prix spectators were able to see it for themselves.

Similarly, de Palma completed the entire race without changing tires, and Goux had only one flat tire, which had nothing to do with the quality of the tires. Pirelli clearly outperformed all American tires.

All competitors used Rudge-Whitworth wheels, which is the highest praise for this well-designed mechanism. Its resistance was remarkable, and this is yet another victory for the metal-spoked wheel, which is clearly the best in terms of safety and performance.

In carburetors, there was a resounding French victory with Claudel on the honor roll. Claudel does not wait for us to congratulate him on something that seems quite natural and that everyone could see, as the Duesenberg and Ballot engines ran smoothly.

It should be noted that the cars that finished the race were equipped with Hartford shock absorbers, so engineer Repusseau’s gamble paid off handsomely. This fact should be emphasized, as the road was in terrible condition due to three months of drought that had literally torn up the surface.

Only two spark plugs caused any trouble today. One is American, the A.C. from our excellent friend Champion; the other is French, the Sol, which I am pleased to have been the first to recommend to manufacturers as particularly suitable for use in a high-compression engine.

Finally, I would add that the Duesenbergs used the Ekip product that I mentioned recently.

The drivers

We had nothing but “aces” at the start of the Grand Prix, and events proved this to be true.

The winner proved himself to be in a class of his own: it must be said that, following his crash with Inghibert, Murphy was still in pain and started the race with a broken rib and his chest covered in silicate bandages. Until this morning, his participation was in doubt, and at one point there was even talk of entrusting Murphy’s car to the excellent Hémery.

I repeat, all the drivers were wonderful, and it would be impossible to name them all. However, let us mention Goux, whose cut on his wrist reopened and ended up covered in blood.

Finally, I would like to single out three men who today earned unanimous admiration: André Boillot, André Dubonnet, and Albert Guyot. André Boillot brought back the virtuosity of his brother Georges and set a nice record, changing a wheel at the grandstands in 17 seconds! He set off again to the cheers of the crowd.

André stopped six times at the stands with a total stop time of just over 18 minutes. Take that away, along with his six extra braking and starting maneuvers, and you’ll see that Boillot could have finished second. This is worth noting. André Dubonnet fully confirmed what I wrote about him after his fine victory in Boulogne.

With a car taken at short notice, four days before the race, he finished fourth, second in the Duesenberg team.

And finally, Albert Guyot, probably the most flexible of all the current drivers and the one who tires a car the least. With 50 kilometers to go, he was second when bad luck struck and caused him to lose a place that seemed assured.

For 1922

And I can only repeat what I wrote before the race itself: this 3-liter rule, which has brought so much progress and so many benefits, has had its day. We need something else next year. What? It’s up to the sports commission to tell us.

Personally, I vote for a maximum engine capacity of 2 liters. Think of what Goux’s Ballot has achieved today with a maximum weight of 750 kilos! (I say “maximum” because our steelmakers need to be shaken up), and above all, I vote for a single driver on board. This last reform seems urgent to me.

However, none of this is the most important thing; we must announce today, or tomorrow at the latest, the organization of the 1922 A.C.F. Grand Prix, even if it means studying the rules to give them to us in October. Let’s not dwell on a defeat which, if we accept it without a future, would have serious consequences.

C. Faroux.

JIMMY MURPHY, the winner – A STATEMENT FROM THE WINNER

— The French public is truly loyal to the sport, and their cheers filled me with joy. Without false modesty, I am very proud of my victory, because I found myself up against remarkably well-prepared competitors who fought me tooth and nail until the very end.

“Hurrah! for France and the French drivers.” – Signed, Jimmy Murphy

The Consecration of the Grand Prix

is that of the “Delco” ignition system; this system, developed by Continsouza, proved itself superior to all others yesterday at La Sarthe, as it was fitted to the winning car, Murphy’s Duesenberg.

The major events of the year prove the excellence of the “Delco” ignition system, which came first at the Circuit de la Corse, first again at the Coupe Georges Boillot (Boulogne-sur-Mer), and finally first at the A.C.F. Grand Prix.

This ignition system represents a huge step forward, and its value is recognized by the major manufacturers. Soon, all motorists will want to equip their cars with Delco ignition systems. To do so, they will contact the headquarters of the large company at 148 Avenue Malakoff.

The photos.

Page 1. – GOUX – Third in the standings and first among French drivers, in the 2-liter Ballot.

Murphy speeding on lap 51. – DE PALMA (in Ballot) – First among French cars. – The victorious Duesenberg. At the wheel: Murphy.