In 1921, Italy organized their first Grand Prix, for which a 17.3-kilometre long triangular road course just south from Brescia was prepared. It became known as the Brescia-Montichiari track, consisting of two long straight roads comined with a third slight curved connection between both straights. It also clould serve as a scene for aeroplane. In the week of 4-11 september 1921, several races were held, such as one for Voiturettes, one for motorcycles and even one for aeroplanes. The Grand Prix on 11 september only sa six contestants; three Ballots and three Fiats. The race was won by Jules Goux in a 3.0-litre Ballot with Chassagne also in Ballot a fine second. Finally a win for Ballot, that were shod by Italian Pirelli tyres.

Text and photos with courtesy of Internet Archive www.archive.org compiled by motorracinghistory.com, translated by DeepL.com

L’Illustrazione Italiana, Vol. XLVIII, No. 37, 11 September 1921

THE SPEED FESTIVAL AT THE BRESCIA CIRCUIT.

Everyone is racing these days in and around Brescia: cars in the race, cars not in the race, horse-drawn carriages, steam trams, even pedestrians and, if you’ll allow me, airplanes. Despite the old signs posted on the streets: “Slow down – dangerous curve – walk pace – slow down,” all the cars and every being equipped with energy develop maximum speed and produce the loudest noises: the law of moderation, the advice of prudence, consideration for the ears and safety of others are abolished for the duration of the circuit, which officially lasts one week, September 4-11, while, from a musical point of view, it began seven days earlier! … it began seven days earlier! “Feverish eve – thunderous crescendo – the dawn of the engine”: these are the phrases that preceded the maximum noise in the newspapers.

For goodness‘ sake, let’s not focus our attention exclusively on the six cars that chased each other madly from 8 a.m. to noon on the 4th, between Fascia d’Oro and Montichiari. That’s the picture, but the setting is even more picturesque and has even political significance. Yes, because when 150,000 people flock from all over northern Italy to reinforce, even if only for a day, the population of Brescia and spend a sleepless night under the stars – or in the drizzle, making noise and occupying the best spots along the 17 kilometers of the track, when all these joyful people gather in the presence of the King and the Prime Minister, it means that the country is not doing too badly, that it is regaining its well-deserved serenity. If it were possible to provide a sporting attraction of the caliber of September 4 once a week, the Rome pact on social pacification would be a fait accompli.

On the night between the 3rd and the 4th, it really seemed as if a piece of Italy was marching along the Brescia-Montichiari road, but a healthy and strong Italy. Don’t ask me for figures. Whether there were five thousand or ten thousand cars, only the Eternal Father knows, who sees everything from above, while no one down below has taken on the mammoth task of counting them: they would have had to stand at the entrance to the track at 10 p.m. on September 3 and count until 10 a.m. on the 4th.

There were so many cars of all kinds, ages, and sizes that their passengers had to walk a kilometer or two to reach the stands. It was like being back on the roads of war: spotlights lit up the straights, revealing fantastic oblong garages, and Bersaglieri, infantrymen, and Carabinieri appeared at every turn, becoming more numerous as the roads narrowed around the moorland on which the track was laid out.

French newspaper correspondents observed that the automobile emporium was in itself a superb achievement, proof that Italy had resumed production with a vigor that France had yet to experience. What’s more, the French praised our circuit as the best organized in the world and the best serviced track. The praise goes above all to Arturo Mercanti.

* * *

No one slept during the night between the 3rd and the 4th. Neither the insomniacs nor the refugees in the rooms: for the latter, thousands and thousands of engines sang a serenade of explosions and exhaust pipes. The guests in their beds wondered whether it was really worth pouring small fortunes into the hands of the landlords…. Yes, because in Italy, the concept of a great event seems inseparable from the concept of a large bill. Quite a few hoteliers, tractor drivers, and innkeepers in Brescia had come to the conclusion that, being within the walls of the Lioness, it was necessary to present lion-like bills. But what did it matter? On the night between the 3rd and the 4th, everyone stayed awake. Even the Prince of Conde would not have slept. And the night was not long. Ninety-nine percent of those who had gathered had to explain the three-liter formula, the parabolic curve, and the reason for the German-Anglo-American non-intervention. Woe betide when the experts explain: between their language and that of the layman stand Babel and modesty. Who dares to confess that they have not understood the three-liter formula when the initiates have already explained it in print and by word of mouth?

The good drinker, as he watched and heard the dawn of the engine from his camp, could not help but ask himself bitterly: „How is it that with three liters I fall to the ground tipsy and a car goes 150 kilometers per hour?

– “No,” replied his neighbor, who was a car driver out for a drive, but out for a drive without a car, being unemployed:

– “No,” three liters refers to the cubic capacity of the eight cylinders in which the mixture develops the power of the engine. A motorcycle, for example, may have a cubic capacity of half a liter.

– “Now tell me about the hyperbolic curve.”

– “Parabolic, you mean. It’s a very tight curve that competitors try to negotiate by combining maximum speed with minimum safety. It’s the most difficult point on the circuit: it’s the sharpest angle of the triangle.”

* * *

Those who had never been to a circuit before thought they were going to see a race capable of generating growing excitement. Instead, the Italian Grand Prix seemed like a wedding where the best moments are the first ones. Then come the disappointments. Engagement: the three reds – the Italians – and the three whites – the French – chat for ten minutes before the start, about this and that in front of their cars lined up in starting order. Interlude: two French cars had been pushed into their places in front of the royal grandstand after the King’s arrival, but it is said that a Parisian woman remarked: „We are unsurpassed in our liveliness, gracefully assuming attitudes that provincials would consider inappropriate.

Let’s continue: the two groups of rivals chat pleasantly as if the duel did not concern them At a glance, the six drivers seem, affectedly, all the same: slender figures, clean-shaven and sunburnt faces, flat, indifferent expressions. People with strong bodies and brains so adapted to their task that they seem to be the essential organ of the car.

Two minutes before the start, the six cars, shaped like slender rhombuses, three red (the Italians) and three blue (the French), are cranked to life. The crews climb aboard. The timekeeper, like an orchestra conductor, holds his precision instrument in his left hand and counts down the seconds to the start with precisely timed gestures of his right hand. The novice imagines that at the start, the car will shoot off like a champagne cork. But no.

The driver waves, smiles slightly, and seems to be going for a stroll.

* * *

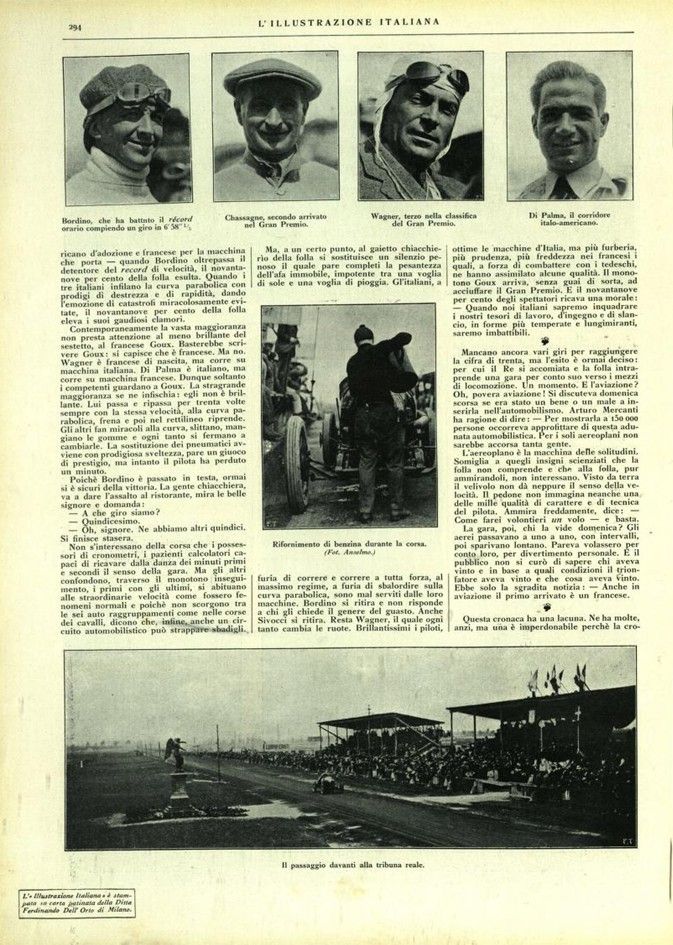

Only after the first lap does the novice get the thrill of speed: that thrill he set out to experience from various points in northern Italy. A roar approaches, a racing car speeds by; a dot disappears: here are Bordino’s 150 kilometers, the fastest of the day. When Bordino overtakes Di Palma—Italian by birth, American by adoption, and French by the car he drives—when Bordino overtakes the speed record holder, ninety-nine percent of the crowd cheers. When the three Italians take the parabolic curve with prodigious skill and speed, giving the thrill of catastrophes miraculously avoided, ninety-nine percent of the crowd raises its joyful clamor.

At the same time, the vast majority pay no attention to the least brilliant of the sextet, the Frenchman Goux. It would be enough to write Goux: it is clear that he is French. But no. Wagner is French by birth, but he races in an Italian car. Di Palma is Italian, but he races in a French car. So only the experts look at Goux. The vast majority don’t care: he is not brilliant. He goes round and round thirty times at the same speed, brakes at the parabolic curve, and then picks up speed again on the straight. The others perform miracles on the curve, skidding, wearing out their tires, and occasionally stopping to change them. The tires are replaced with prodigious speed, like a magic trick, but in the meantime, the driver has lost a minute.

Since Bordino has taken the lead, victory is now assured. People chat, rush to the restaurant, eye the beautiful ladies and ask:

– What lap are we on? – Fifteenth. – Oh, my. We have another fifteen to go.

It will be over tonight.

The only people interested in the race are the owners of stopwatches, patient calculators capable of gleaning the meaning of the race from the dance of minutes, seconds, and tenths of a second. But the others confuse the first with the last in the monotonous chase, get used to the extraordinary speeds as if they were normal phenomena, and since they don’t see groups of six cars as in horse races, they say that, in the end, even a car circuit can elicit yawns.

But at a certain point, the cheerful chatter of the crowd is replaced by an uncomfortable silence, which seems to complete the heaviness of the still, oppressive heat, caught between a desire for sun and a desire for rain. The Italians, by dint of racing and racing at full throttle, at maximum speed, by dint of astonishing the crowd on the parabolic curve, are poorly served by their cars. Bordino retires and does not respond to those who ask him about the nature of the fault. Sivocci also retires. Wagner remains, changing his wheels from time to time. The drivers are brilliant, the Italian cars are excellent, but the French are more cunning, more cautious, more cool-headed, having assimilated some of these qualities from their battles with the Germans. The monotonous Goux arrives, without any trouble whatsoever, to win the Grand Prix. And ninety-nine percent of the spectators draw a moral:

– When we Italians learn to channel our treasures of work, ingenuity, and enthusiasm into more temperate and far-sighted forms, we will be unbeatable.

There are still several laps to go before reaching thirty, but the outcome is now decided: so the King takes his leave and the crowd embarks on a race of its own towards the means of transport. Wait a minute. What about aviation? Oh, poor aviation! Last Sunday, there was a debate about whether it was a good or bad idea to include it in motor racing. Arturo Mercanti is right when he says: „To show it to 150,000 people, we had to take advantage of this motor racing event. Not so many people would have come just for the airplanes.

The airplane is the machine of solitude. It resembles those distinguished scientists whom the crowd does not understand and who, although admired, are of no interest to the crowd. Seen from the ground, the aircraft does not even give a sense of speed. The pedestrian cannot even imagine one of the thousand qualities of character and technique of the pilot. He admires it coldly and says, ‘How I would love to fly,’ and that’s it.

Who saw the race on Sunday? The aircraft flew by one by one, at intervals, then disappeared into the distance. They seemed to be flying on their own, for their own enjoyment. The public did not care to know who had won, under what conditions the winner had won, or what he had won. They only had the unwelcome news:

“Even in aviation, the first to arrive is a Frenchman.”

* * *

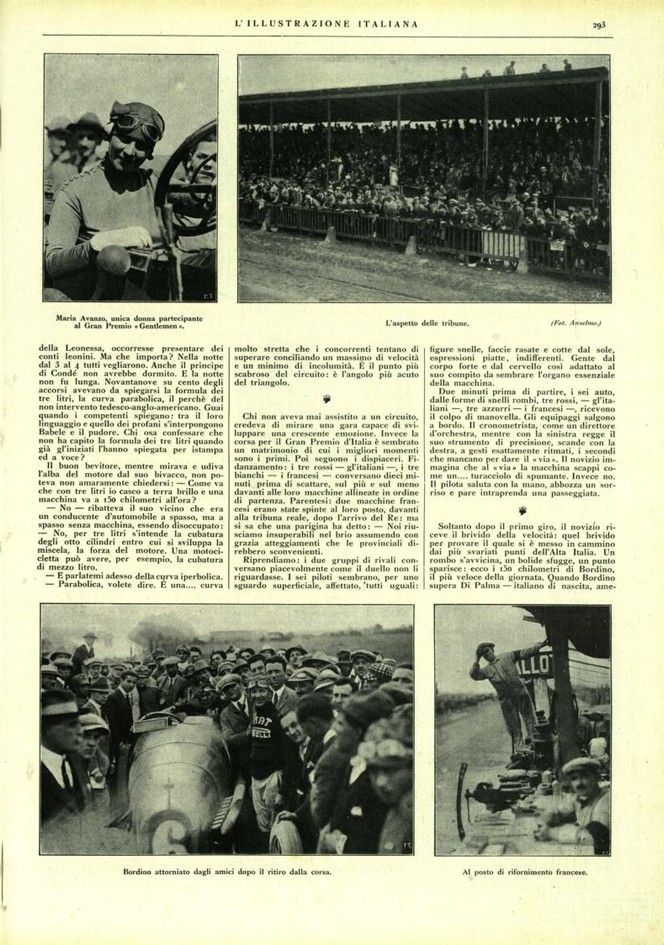

This report has a gap. It has many, in fact, but one is unforgivable because the report should have immediately mentioned that among the pilots who rushed to the circuit and paraded their cars in front of the King, there was also a lady, a beautiful young lady, all Italian in her dark, large, deep eyes, in her gentle yet determined expression, in her slender, harmonious figure. On Sunday, her black hair was hidden under her helmet and she was dressed in a tight-fitting vermilion racing suit. It is the woman who makes the outfit elegant. I, who abhor interviews, instead inflicted one on Baroness Maria Antonietta Avanzo Bellan, who is participating today, September 11, in the gentlemen’s race, driving a small car. I reproduce the questions and answers:

– How long have you been driving cars?

– For two years.

– Have you ever hit anyone?

– Never.

– How did you get into the sport?

– Read this.

She showed me a magazine, which reported that the baroness took up driving to forget a disappointment. Her preference for the road is all the more flattering given that the baroness, as a daughter of Venice, certainly had to overcome the appeal of motorboats.

But these boats are too slow, while the baroness loves the dizzying speeds with which she has won several races and would have won even more laurels if her car’s fuel tank had not been sabotaged with a hole during the Buix race. But today, the noblewoman, racing among gentlemen, will have no trouble.

A magazine summed up her impressive performance with the phrase “grace conquers glory,” a phrase that worked well in the press box on Sunday as an antidote to the abstruse three-liter formula.

* * *

Another soldier wandered in front of the stands shouting the latest news about the race through a megaphone, while the army of 150,000 hungry, dusty, and sleepy people poured into Brescia, amid the clamor of all the dialects and the parade of vehicles bearing the names of cities from Genoa to Treviso….

As during the return of prisoners from Austria after November 4, 1918, last Sunday the provincial trains passed by, packed inside and out: people on the roofs, on the buffers, and even in the engine, elbow to elbow with the fireman. A self-evident ticket inspector observed: “You earn less when there are so many people than on days when the cars are empty.”

The return journey, as we know, is fraught with discontent. The spectators in the stands exchanged confidence: „It would have been better for me to stand in front of the parabolic curve.

– I was wrong to stand in the central stands.

– “I’ve got a stiff neck.” The cars were going in one direction, the planes in another. When they passed at the same time, I turned to the right, while I wanted to look to the left as well.

* * *

On Sunday evening, Milan, Bergamo, Verona, Mantua, and Parma roared with engines: all cars coming from Brescia. And each city, listening to its own portion of music, was able to get an idea, multiplied by three, of the diabolical Brescian symphony on the night and afternoon of September 4.

As on the way there, on the way back, under the lash of a storm, each car tended to overtake the other, in a greed for supremacy that was never satisfied because there was always some new rival to catch up with. And the races took place on the roads of Lombardy, Veneto, and Emilia, to the amazement of the villagers and the fatigue of the police, forest rangers, and civic guards, intent on filling their notebooks with numbers: the numbers of the cars returning from the festival of speed. “Oh, tomorrow,” murmured the law enforcement officers, „we’ll have our own party!

OTELLO CAVARA.

Photos.

Page 291.

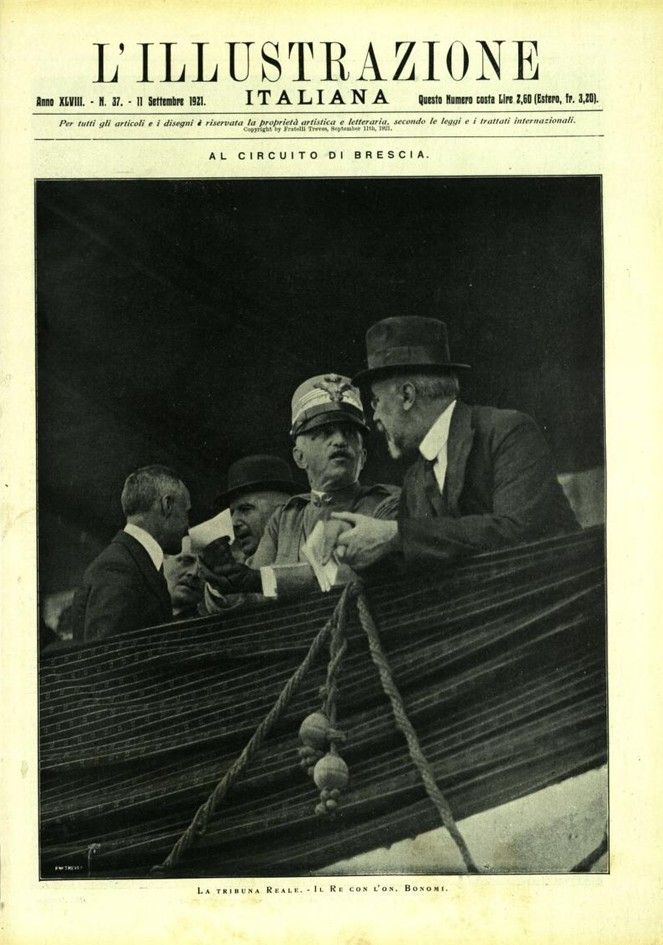

The King, Prime Minister Bonomi, ministers, and authorities on the royal grandstand follow the race. (Photo: Anselmo.)

Page 292.

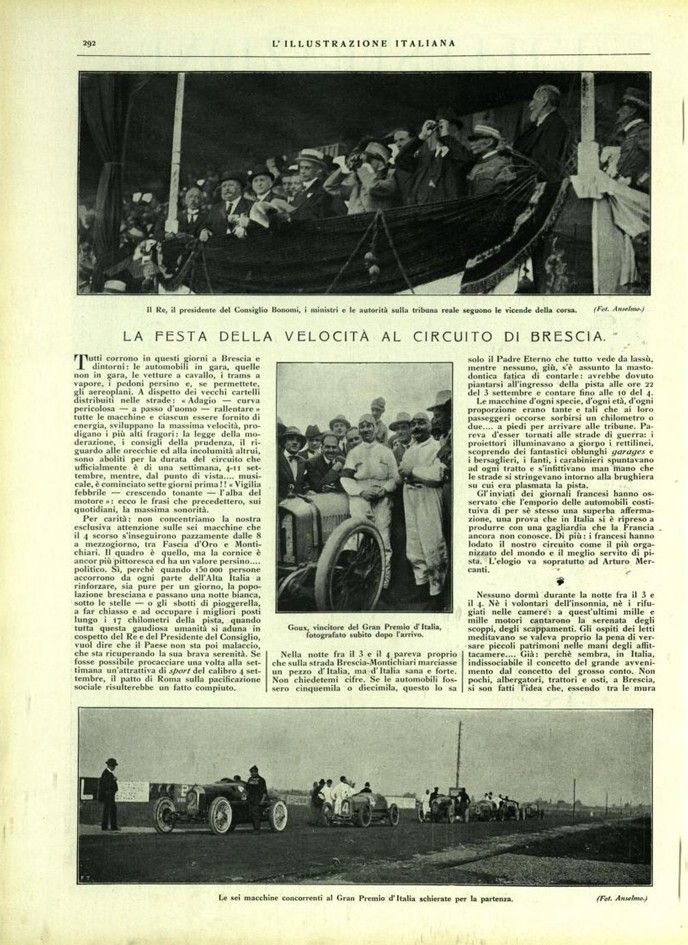

Goux, winner of the Italian Grand Prix, photographed immediately after the finish.

The six cars competing in the Italian Grand Prix lined up for the start. (Photo: Anselmo.)

Page 293.

Maria Avanzo, the only woman participating in the Gentlemen Grand Prix.

The appearance of the grandstands. (Photo: Anselmo)

Bordino surrounded by friends after retiring from the race.

At the French refueling station.

Page 294.

Bordino, who broke the hour record by completing a lap in 6’58″1/5

Chassagne, runner-up in the Grand Prix.

Wagner, third in the Grand Prix standings.

Di Palma, the Italian-American driver.

Refueling during the race. (Photo: Anselmo.)

Passing in front of the royal grandstand.

L’Illustrazione Italiana is printed on coated paper by Ferdinando Dell‘ Orto in Milan.

Page 295.

The entrance to the circuit. – Breakfast in the car. (Photo: Anselmo.)

Pages 298–299.

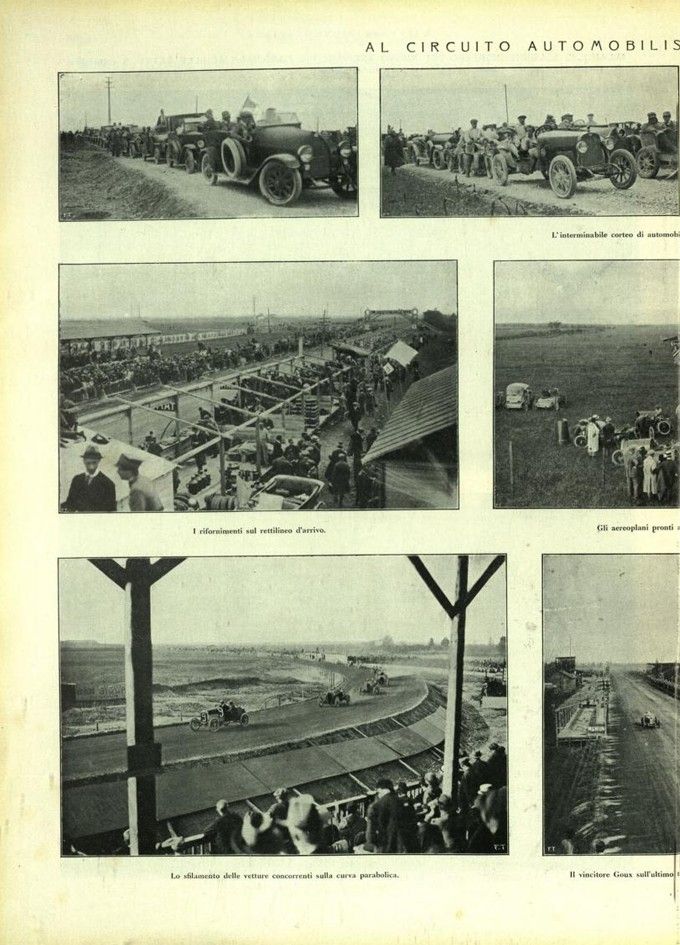

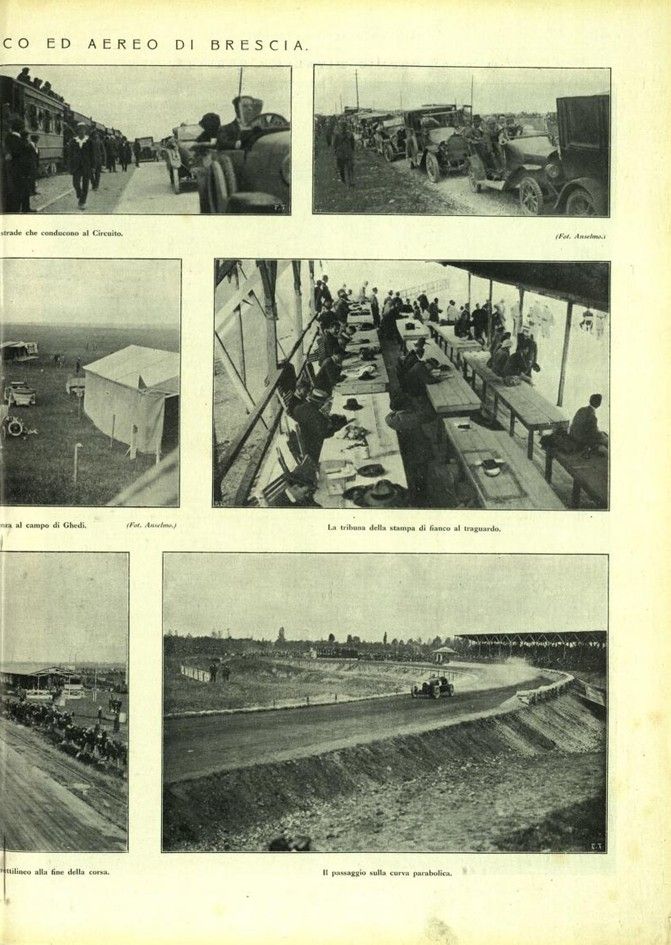

AT THE BRESCIA MOTOR AND AIR CIRCUIT

The endless procession of cars on the roads leading to the circuit (Photo: Anselmo.)

Refueling on the home straight. – Airplanes ready for takeoff at the Ghedi airfield. – The press box next to the finish line. (Photo: Anselmo.)

The parade of competing cars on the parabolic curve. – Winner Goux on the last stretch of the home straight at the end of the race. – Passing through the parabolic curve.

Page 300.

THE ITALIAN GRAND PRIX IN BRESCIA.

Wagner chases the competitors after refueling. – Chassagne passes the parabolic curve.

Urgent Pirelli Milan – Fr Brescia 205 87 5 050

I AM HAPPY TO INFORM YOU THAT THE PIRELLI TIRES FITTED ON MY RACE CARS AT THE BRESCIA CIRCUIT, COVERING 513 KM AT AN AVERAGE SPEED OF 144 KM/H, WERE COMPLETELY SATISFYING AND THAT MY CARS COMPLETED THE ENTIRE RACE WITHOUT CHANGING A SINGLE TIRE, FINISHING IN 1ST AND 2ND PLACE AND BREAKING ALL WORLD RECORDS. THE CONDITION OF THE TIRES AT THE FINISH LINE ALLOWS ME TO ESTIMATE THAT MY CARS CAN RUN THE RACE AGAIN WITH THE SAME TIRES = BALLOT

Facsimile of the telegram sent to the Italian company Pirelli & C…..

“Goux and Chassagne completed thirty laps of the circuit with its few but difficult curves; yet the Pirelli tires returned intact to the start” …. “Gazzetta dello Sport.” Sivocci after the stands. – Goux, winner of the race, shakes hands with Mr. Ballot.