An interesting Italian article; actually the first that I found. It contains a lot of text, but it’s worth while reading! It gives a fair indication, how Italian automobile journalists referred to the first Italian races and victories of Italian cars in those early days. Proud as each nation was on the success of their industry.

Text and fotos with courtesy of Museo dell’Automobile di Torino, compiled by motorracinghistory.com

La Stampa Sportiva, Anno IV, N. 38, Torino, 17 Settembre 1905

Il Triple trionfo della Itala nel Circuito de Brescia.

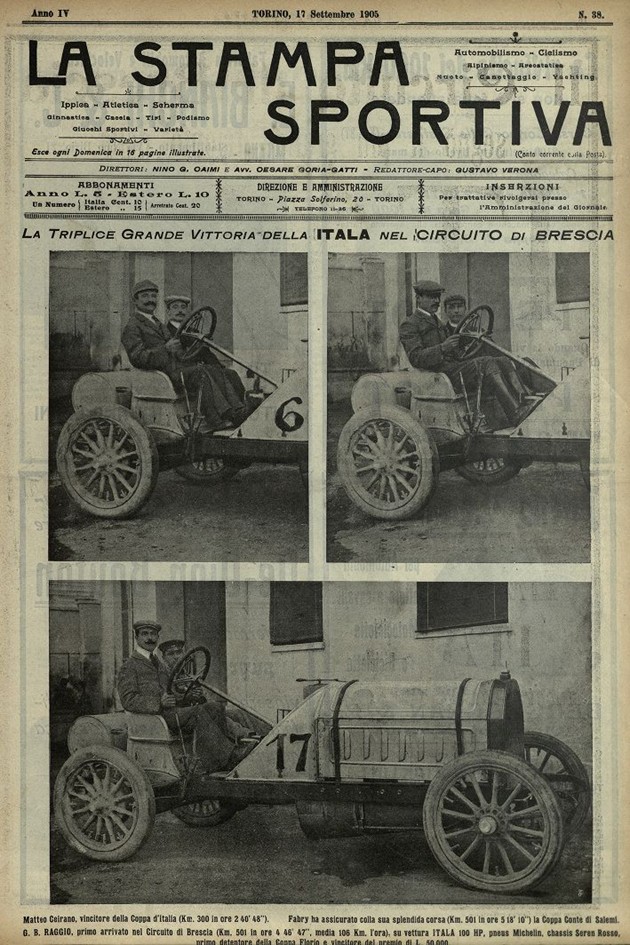

La triplice Grande Vittoria della ITALA nel Circuito di BRESCIA

Matteo Ceirano, vincitore della Coppa d’Italia (Km. 300 in ore 2 40′ 48″).

Fabry ha assicurato con la sua splendida corsa (Km. 501 in ore 518′ 10″) la Coppa Conte di Salemi.

G. B. RAGGIO, primo arrivato nel Circuito di Brescia (Km. 501 in ore 4 46′ 47″, media 106 Km. l’ora), su vettura ITALA 100 HP, pneus Michelin, chassis Seren Rosso, primo detentore della Coppa Florio e vincitore del premio di L 50.000.

LA SETTIMANA AUTOMOBILISTICA DI BRESCIA

Il triplice trionfo della ITALA – Il cammino d’una giovane fabbrica – Significato delta sua Vittoria

Il successo sportivo del meeting bresciano – Lodi e appunti al Comitato ordinatore – Come si è svolta la Corsa.

Fu una bella corsa e un grande, insperato successo per l’industria italiana.

Eravamo andati a Brescia convinti di assistere ad una lotta strenua, che forse preparava delle sorprese, ma non avremmo saputo augurare a noi stessi una sorpresa maggiore e migliore.

Sapevamo già di avere in Italia una fabbrica automobilistica che aveva saputo imporre il suo valore a tutto il mondo sportivo e industriale, e aveva guadagnato nella recente corsa della Gordon Bennett ammirazione e plauso al genio e al lavoro italiano.

Oggi a Brescia è venuta ad allinearsi al suo fianco una giovane consorella, che ha fatto un meraviglioso cammino in brevissimo tempo, e che attesta con la sua brillante affermazione che non abbiamo soltanto una fabbrica, ma anche un’industria, che, oltre al nome di Fiat, vi è quello di Itala, e dopo queste due vi è tutto un semenzaio di fervore da cui nuove promesse di lavoro attendono di uscire al sole delle vittorie e della gloria.

E ci perdonino i nostri amici della Fiat, a cui la fortuna ha voluto giocare un capriccioso tiro, se noi osiamo affermare che ii risultato della riunione di Brescia, colla triplice vittoria della Itala, è per l’industria e per l’Italia ancor più significante e lusinghiero di quello che avrebbe potuto essere con una nuova vittoria della Fiat, e noi che conosciamo a quali alti intendimenti inspirino l’opera loro i dirigenti della grande fabbrica di Corso Dante, siamo convinti che non ce ne vorranno per questa nostra affermazione.

Una nuova vittoria della Fiat poco o nulla avrebbe aggiunto alla gloria di questa fabbrica, che ormai ha nel mercato mondiale un nome che più non si discute. La triplice vittoria della Itala in una riunione così importante come quella di Brescia e su un lotto di avversari come quelli che contro di essa si sono allineati, mette questo nuovo astro allo zenit del firmamento automobilistico, e mentre riafferma il valore di tutta la nostra industria automobilistica, facilitando la strada alle future vittorie di altri nomi, di altri valori, di altre fabbriche, è anche un giusto premio alle tenaci e operose intelligenze che hanno saputo preparare questo giorno di gloria.

Bisogna ricordare le prime battaglie nella modesta officina di via Artisti, quando l’Itala faceva i suoi primi passi e ne erano padri amorosi e premurosi il piccolo Bigio, il grande Grosso Campana e Matteo Ceirano, il tecnico studioso, l’uomo dalle poche parole e dai molti I fatti. Bisogna ricordare la fede bella e intensa di quei giorni di preparazione per trovare il segreto della riuscita d’oggi. Erano allora i tempi in cui il nome della Fiat usciva dall’ombra e cominciava a rivestirsi dei bei colori delia fama e del successo, e nella giovane fabbrica (rampollata dal tronco rigoglioso di quella Ditta Ceirano, che fu tra i pionieri dell’automobilismo), le affermazioni altrui non generarono invidia, ma ammirazione, ed erano incitamento e sprone a lavorare. ) E ricorderemo quelle prime vetture uscite dalla novella officina per tentare la prova del Cenisio, finite alla vigilia della partenza e che si piazzavano brillantemente, vincendo nella velocità la categoria vetture leggere con Ceirano 1° e Bigio 2°, e nella categoria turisti con Raggio, che debuttava come guidatore in corsa, ottenendo un secondo posto.

Dall’anno scorso quanto cammino! Il trasloco nelle grandiose officine in via Petrarca, la trasformazione dell’Itala in grande Società anonima con alla testa una personalità del mondo finanziario, come il comm. Figari, la brillantissima e promettente presentazione dell’Esposizione di Torino, quindi il successo della corsa Susa-Moncenisio e il tentativo delle Ardenne e la grande battaglia e la grande vittoria di Brescia.

Come si vede, un cammino segnato da pochissime tappe, ma di quale importanza!

Ed ora che a tanti sforzi, a una fede così sicura, a un valore così indiscutibile, ha arriso la vittoria, noi comprendiamo tutta la giusta esultanza che deve allietare Matteo Ceirano e Guido Bigio, i due artefici del gran successo, G. B. Raggio, il fortunato, abilissimo conduttore, che oggi vede il suo nome passare innanzi a quello dei Lancia, dei Cagno, dei Nazzari degli Héméry, dei Duray, dei Rougier, dei Florio, ossia di tutti coloro che il mondo automobilistico saluta come gran maestri, del comm. Figari, di Cattaneo, di Fubini, di Carenzi, di Poggi, e di tutta la schiera dei fidati amici della Itala, che ne hanno incoraggiato e sostenuto i primi passi e che hanno diritto alla loro parte nel plauso, con cui unanime l’Italia saluta questa nuova fabbrica venuta a comprovare in faccia al mondo, colla genialità del lavoro latino, il risveglio e la rinascenza italiana alla vita industriale.

**

Ed ora, detto della vittoria della Itala e del suo significato, che ne sono le note salienti, dobbiamo parlare della riunione di Brescia, come avvenimento sportivo.

Il successo era preveduto e convenientemente preparato; esso non poteva mancare.

La brillante affermazione del passato anno dava diritto di credito e di fiducia ai volonterosi componenti il Comitato bresciano, che con una buona volontà, di cui non è molto comune l’esempio (pur troppo) in Italia, si erano accinti al difficile compito di organizzare anche fra noi una grande corsa internazionale.

Basta aver visto un po‘ da vicino che cosa vuol dire organizzare una simile riunione, per comprendere che il grande entusiasmo sportivo dei componenti il Comitato bresciano doveva aver avuto in rinforzo un esponente ben alto di amore per la propria città (a cui questo avvenimento doveva portare così largo profitto di conoscenza e di affari), per farli accingere a compito tanto arduo, Da questo punto di vista, intera e compieta deve andare la nostra ammirazione e il plauso del mondo sportivo italiano al conte Martinoni, al senatore e al conte Bettoni, al conte Oldofredi, al conte Martinengo, che del Comitato furono anima e mente, e al cav. Minetti, al ragioniere Mercanti e al sig. Costa, che ne furono il braccio operoso e instancabile.

Ad essi può essere riconoscente la città di Brescia che ha visto accorrere nelle sue mura, affollare le strade, riempire gli alberghi, caffè e alloggi privati, una folla innumere di forse oltre 20.000 persone, accorse da ogni parte d’Italia per assistere al tanto atteso spettacolo. Tanto che se le voci corse sulla mancanza di un rilevante contributo finanziario che era stato promesso e annunciato sono vere, noi crediamo sia più che doveroso l’intervento del Municipio a nome della città, il cui commercio ha tratto indiscutibili e non trascurabili vantaggi da questo grandioso avvenimento.

* *

E veniamo ora alla grande giornata. Ridire tutta l’animazione, elencare tutti i nomi noti che popolavano le grandi tribune erette nella brughiera di Montichiari, è cosa impossibile. Tutto il mondo motorista italiano era là e, nota nuova e simpaticissima, abbondavano le signore dai delicati profili avvolti nei fini veli.

È questa numerosa partecipazione dell’elemento femminile alla vita automobilistica una delle note caratteristiche del meeting bresciano, ed era bello e confortante vedere da quasi tutti gli infiniti automobili, nel pomeriggio di sabato al corso di Brescia, scendere graziose ed eleganti silhouettes di chauffeuses.

Indicibile lo spettacolo delle centinaia e centinaia di vetture e di veicoli che fin dalle prime ore del mattino si allinearono sulla strada che conduceva alle tribune. Nel buio profondo della notte la lunga schiera di grandi, immensi occhi dei fanali assumeva un aspetto indimenticabile. E alla prima alba le tribune si scoprirono già affollate di pubblico, come affollato era ogni punto del percorso, ogni paese, ogni svolto di strada. Forse altre 200.000 persone hanno seguito con interesse lo svolgersi di questa gara grandiosa.

Le partenze sono cominciate puntualmente alle 6,30, sotto la direzione del cronometrista Tampier e dei membri della Commissione sportiva: marchese Soragna, marchese Ferrerò, Berteaux, conte Terzi, conte Martinoni, Minetti, ecc.

L’ordine di partenza fu quello da noi precedentemente indicato e a 4 minuti di distanza partono: Héméry sulla sua piccola Darracq, in cui molti vedono la prima arrivata, quindi Lancia calmo e sereno e che porta con se le maggiori speranze degli italiani.

Terzo Le Blon, che è riuscito ad avere pronta la vettura Isotta Fraschini alla vigilia e che parte più che altro in prova di col auto; quarto Rougier (De Diétrich), che parte con uno splendido demarrage; quinto il giovane Albert Clément, venuto all’ultimo momento, insieme a Carlos, a rafforzare il lotto francese con le due eccellenti Clément Bayard, sesto Matteo Ceirano, che ha come compagno Bigio, e con sicura fiducia porta al battesimo la sua Itala, che dal suo primo apparire è giudicata un capolavoro meccanico dai suoi stessi avversari.

Settimo parte Cenzino Florio, il brillante sportsman siciliano, il mecenate della riunione di Brescia, che il pubblico giustamente saluta con speciali acclamazioni di riconoscenza. Peccato che esso parta curvo sul manubrio d’una vettura estera, a capo d’un piccolo esercito di Mercédès da lui qui condotte a contrastare la vittoria all’industria italiana.

Poi si ricomincia la serie: Wagner su Darracq, Nazzaro su Fiat, Duiay su Diétrieh, Carlès su Clément Bayard, Fabbry su Itala, Mariaux su Mercédès.

Il terzo giro sembra riservato ai corridori gentlemen: dopo Cagno su Fìat e Caullois su De Diétrich (che ha rimpiazzato Gabriel), ecco Raggio sulla terza Itala, e dopo Gasteaux su Mercédès, ecco Weillschott su Fiat, quindi Cortese su Mercédès, e ancora Gandini su Fiat, e ultimo parte, alle 7.52, Thery su Mercédès.

Impressionanti soprattutto i demarrages velocissimi delle prime tre Fiat, delle De Diétrich e delle Itala. Ottimamente parte anche Florio.

È appena partito l’ultimo, è cioè trascorso l’22 dalla partenza del primo, che già si acuisce l’attesa del passaggio del primo giro.

I due favoriti sono Héméry e Lancia. Dal loro passaggio si potrà giudicare come si delinea la lotta. Héméry, favorito dalla sorte, e che essendo partito primo non ha il grande svantaggio della polvere, sarà raggiunto e sorpassato da Lancia, che è partito 4 minuti dopo? Ecco la comune domanda che ansiosamente corre di bocca in bocca. Ma uno squillo risuona da lontano. Ecco il primo che arriva, è in vista, chi è, qua numero? Eccolo, passa il num. 1. Héméry è passato. Ha compiuto l’intero giro di 167 km. in ore 1 29′ 54″.

La marcia è adunque sostenuta a una media di 110/112 km. l’ora, senza tener conto delle possibili neutralizzazioni.

La battaglia si annuncia accanita. E Lancia? Se giunge in meno di 4 minuti può ancora aver guadagnato terreno. I minuti passano, 3, 4, 5, 10, e nessuno compare. Un’ombra passa sul viso di chi spiava l’apparire del campione italiano.

Risuona uno squillo, ecco il secondo: «Lancia, Lancia», dicono mille voci. No, è il numero 4, è Rougier, che è passato alle 8,14, e cioè 15 minuti dopo Héméry.

E Lancia? si chiedono tutti. Lo spettro della panne si avanza dietro l’immagine del favorito.

Ma eccolo finalmente Lancia che viene, passa come un fulmine, ha però il tempo di accennare alle gomme e di spiegare che lì sta la ragione del suo ritardo. Lancia al primo giro ha 12 minuti di ritardo su Héméry. Le speranze degli italiani si scuotono e si rivolgono a Nazzaro, a Cagno, a tutti gli altri noti campioni. Ma ecco Ceirano che passa meravigliosamente bene, solo 6 minuti dopo di Lancia. Essendo partito 20 minuti dopo Héméry, non ha che 4 minuti di ritardo su lui. Ecco, dunque, le Itala entrare in gara e contare nella partita.

Evidentemente però la mancanza di un servizio di segnalazione e di telefono rende buio lo svolgimento della corsa, e i successivi passaggi di Florio, Duray, Fabry, Nazzaro, ecc., non dicono nulla, nulla si sa dei tempi di arresto forzato ai controlli. È questo uno dei maggiori inconvenienti dell’organizzazione, e per quanto sembri debba imputarsene la colpa a un mancato e promesso servizio militare, non possiamo nascondere che il Comitato ha lui stesso guastato l’interesse dello svolgimento della gara, che avendo dovuto essere interrotta da neutralizzazioni, doveva necessariamente e in tempo debito essere corredata di un servizio di segnalazione.

Dai passaggi successivi si può solo vedere che l’Isotta-Fraschini di Le Blond si è fermata prima di aver compiuto il primo giro, che pure fermati sono Cagno, Mariaux, Cortese, Clément, Gandini.

Carlès e Therry sono in grande ritardo.

Al secondo giro, con grande sorpresa, passa primo Rougier, che ha sopravanzato di ben 8 minuti Héméry, partito 12 min. prima di lui. Héméry passa secondo e accenna anche lui a panne di pneumatici. Questa volta lo segue Lancia, che è a soli 7 minuti da lui. Avanza pure Ceirano, che passa 12 minuti dopo Lancia, e Duray che sembra aumentare le chances di vittoria della Diétrich.

Raggio passa 10°, seguendo da vicino Nazzaro, che ha ripreso terreno. Di chi sarà la vittoria? Ceirano, che è passato con tre soli pneumatici e camminando sul cerchione (aveva commesso la imprudenza di partire senza neppure una gomma di ricambio), è arrestato poco dopo il traguardo del 2° giro, e deve rinunciare alla corsa. Egli però, entrando nelle tribune, ci dice con un sorriso enigmatico: la Coppa d’Italia deve essere nostra!

Ecco un raggio di speranza che si alza sull’orizzonte delle speranze italiane, e che lascia intravedere nei tempi di arresto una chance nuova per noi.

Intanto si conferma che le Itala vanno meravigliosamente bene. Non un colpo mancato, non il più piccolo incidente. Bigio dichiara che non fu potuta mettere la quarta velocità, causa la grande quantità di polvere ; eppure la vettura ha fatto del 120.

Rimangono in gara Fabry e Raggio, e la partita non è dunque perduta con due simili ordigni. Ma chi osa sperare? Per un debutto Itala ha già fatto miracoli: speriamo di vederli classificati. E l’attenzione si porta sui primi tre: Héméry, Rougier e Lancia, a cui pare circoscritta la battaglia.

* *

Siamo al terzo giro. L’ansia cresce per quanto oscilli e sia vago il pronostico.

Squilla la tromba e passa in piena velocità Héméry, che ha così compiuto i 501 km. in ore 5,4’l2″ (tempo lordo). A sette minuti da lui giunge Lancia, che passa a una velocità fantastica.

Marsigliese, marcia reale, applausi. Ma chi è il vinto, chi il vincitore ?

Ognuno, a seconda delle sue convinzioni, fa la proclamazione; intanto Lancia giunge a piedi al traguardo, narra le sue peripezie degli pneumatici, e racconta che, essendo rimasto senza benzina, ha dovuto perdere 10 minuti per andarne alla ricerca e, nel farne poi la provvista, per poco non rimase vittima di un incendio. Egli però annuncia di avere otto minuti di compenso per neutralizzazione, per cui essendo la sua distanza da Héméry di soli 3 minuti, avrebbe una precedenza di 5′ sul francese.

Queste voci si ripetono e si spargono come un baleno per le tribune, dove la vittoria di Lancia è data come cosa sicura.

È troppo desiderata la notizia per non essere creduta immediatamente, e mentre arrivano Rougier, Duray, Florio, Wagner, Nazzaro, Raggio, Fabry, Caullois e Therry, pochi pensano che fra questi appunto possa essere il vincitore.

* *

Da qualche telegramma alla Giurìa, e pare non chiaro neanche quello, si apprende che le neutralizzazioni sono state sensibili specialmente per Fabry, Raggio, Nazzaro, Florio, ecc., ma mentre quell’immenso pubblico sfolla le tribune (sono ormai le due e il sole dardeggia) e si avvia in lungo corteo su Brescia, nessuno pensa alla sorpresa che l’adunanza dei commissari, immediatamente tenuta a Brescia, sta preparando.

E‘, dapprima, un’esclamazione di incredulità, quindi una domanda di conferma, poi una parola di sorpresa, ma quando il marchese di Soragna esce dalla sala della riunione (e sono quasi le 6) e annuncia che dall’esame scrupoloso dei rapporti dei vari i ispettori, dal calcolo esatto dei fogli contenuti nelle scatole delle singole vetture, è risultato li seguente risultato definitivo e ufficiale: è un grido di gioia e di orgoglio nazionale che saluta l’inattesa triplice vittoria della nuova fabbrica italiana.

L’Itala ha vinto, Raggio è primo del circuito. A Ceirano la Coppa d’Italia, all’Itala la Coppa Salemi.

Che splendido, glorioso epilogo per una giornata indimenticabile di lotta, di ansia, di vere e sentite emozioni sportive e patriottiche.

* *

Non conoscendo le neutralizzazioni ad ogni giro, non è possibile fare la posizione esatta dei corridori ad ogni passaggio. Dobbiamo accontentarci di indicare i tempi lordi, che, come appare dalla classifica, hanno subito poi forti varianti per la deduzione delle neutralizzazioni.

Posizione dopo il primo giro.

1. Héméry (Darracq) ore 1,29′ 59″; 2. Rougier (De Diétrich), 1,32′; 3. Ceirano (Itala), 1,33′; 4. Caullois (De Diétrieh), 1, 36′ 56″; 5. Wagner (Darracq), 1,38’49“; 6. Raggio (Itala), 1,39’53“; 7. Fabry (Itala), 1,40′ 39″; 8. Florio (Mercédès), 1, 40′ 45″; 9. Duray (De Diétrich), 1, 41′ 40″; 10. Lancia (Fiat), 1,43’1″; 11. Weillschott (Fiat), 1,43′ 8“; 12. Mariaux (Mercédès), 1,49’1″; 13. Nazzaro (Fiat), 1, 54′ 27″; 14. Carlès (Bayard-Clément), 2,3’30“; 15. Clément (Bayard-Clément), 2,11’6″; 16. Therry (Mercédès), 2,30′; 17. Gandini (Fìat), 2,35′ 36″.

Dopo il secondo giro.

1. Rougier (De Dietrich), ore 3, 6’51“; 2. Caullois (De Diétrich), 3,22’6″; 3. Ceirano (Itala), 3, 25′ 38″; 4. Héméry (Darracq), 3, 26’27“; 5. Lancia (Fiat), 3,29’44“; 6. Raggio (Itala), 3,35’10“; 7. Duray (De Diétrich), 3,36’8″; 8. Wagner (Darracq), 3, 52’24“; 9. Florio (Mercédès), 3, 55’15“; 10. Fabry (Itala), 3,56’2″; 11. Nazzaro (Fiat), 4,1’26“; 12. Therry (Mercédès), 4, 29’4″; 13. Mariaux (Mercédès), 4,50′ 56″; 14. Carlès (Bayard-Clément), 5, 55’58“.

Alla fine del terzo giro.

1. Héméry (Darracq), ore 5,4′ 12″; 2. Lancia (Fiat), 5, 7′ 38″; 3. Duray (De Diétrich), 5,12′ 20″; 4. Rougier (De Diétrich), 5, 17’50“; 5. Raggio (Itala), 5, 21′, 47″; 6. Florio (Mercédès), 5, 40′ 11″; 7. Nazzaro (Fiat), 5, 48′ 52″; 8. Caullois (De Diétrich), 5, 49′ 54″; 9. Fabry (Itala), 5. 50′ 10″; 10. Wagner (Darracq), 5, 54′ 24″; 11. Thery (Mercédès), 6,21’45“; 12. Carlès (Bayard-Clément).

**

Essendo risultati i tempi da dedursi i seguenti:

Raggio (Itala), 35 minuti; Duray (De Diétrich), 16 m.; Lancia (Fiat), 9 m. 44 s.; Héméry (Darracq), 6 m.; Rougier (De Diétrich), 5 m.; Nazzaro (Fiat), 36 m.; Fabry (Itala), 32 m.; Wagner (Darracq), 25 m.; Florio (Mercédès), 11 m.; Caullois (De Diétrich), 16 m.

Si ottiene la seguente classifica ufficiale:

1. Raggio (Itala), ore 4, 46′ 47″ 25; 2. Duray (De Diétrich), 4, 56′ 20″ 45; 3. Lancia (Fiat), 4, 57′ 54″; 15; 4. Héméry (Darracq), 4, 58′ 12″ 25; 5. Rougier (De Diétrich), 5, 12′ 50″ 2/5; 6. Nazzaro (Fiat), 5,12′ 52″; 7. Fabry (Itala), 5, 18′ 10″ 15; 8. Wagner (Darracq), 5, 19′ 2″ 4(5; 9. Florio (Mercédès), 5, 29′ 11″ 45; 10. Callois (De Diétrich), 5, 33′ 44″ 4/5; 11. Thery (Mercédès.), 6, 21’25“.

* *

La media oraria ottenuta da Raggio è di chilometri 104,870 all’ora, e questa alta cifra spiega, con la calda giornata e colle numerose curve della strada, l’ecatombe di pneumatici registrata.

**

Per la cronaca registreremo che di tutte le vetture partenti le Mercédès erano munite di gomme Continental, mentre tutte le altre vetture erano su gomme Michelin.

E mentre qualche collega della stampa ha creduto di affermare che questa corsa era la condanna degli pneumatici, noi crediamo invece poter rilevare il rapido cammino fatto dalla Gordon-Bennett al Circuito di Brescia. Là fu necessario ad ogni giro sostituire il completo treno delle gomme perché risultavano totalmente usate, qui di fronte a disgraziati casi come quelli di Lancia e Héméry, vi sono esempi come Raggio, Duray, Florio, e altri che hanno potuto coprire ben 500 chilometri, a andature superiori ai 100 all’ora, senza dover cambiare nessuna gomma.

È dunque anche questa un’altra affermazione importante della grande rinuione di Brescia; sui risultati della quale noi ritorneremo certamente in prossimi numeri.

* *

Una sola nota noi vogliamo aggiungere alla cronaca di questa indimenticabile giornata, nota che piìi che da spirito critico è inspirata dal desiderio che gli inconvenienti che andiamo a lamentare possano scomparire nelle future desiderate edizioni di questo grandioso meeting.

Augurandoci che le voci che corrono si confermino, anche a lusinghiero attestato di fiducia dovuto ai volonterosi amici che compongono il Comitato della Settimana Bresciana, noi crediamo lecito esternare i seguenti desideri:

che scompaia quel carattere antipatico e antinazionale che sembra aver inspirato la Direzione di questa prova, di cui si sono cercati in Francia inspiratori, consiglieri e tribolanti; che sia provveduto ad un servizio di informazioni per la stampa presso il Comitato, affidato a persona adatta a disimpegnarlo e che sappia che i giornalisti italiani valgono almeno quanto quelli francesi e si usi a noi quelle elementari cortesie a cui ci dà diritto l’opera nostra volonterosa e disinteressata;

che siano eliminate possibilmente le neutralizzazioni; sia provveduto a un servizio completo e sollecito di segnalazioni su tutto il percorso; sia resa la strada del percorso meglio atta alla prova, eliminando il grave pericolo della polvere; sia provveduto al delicato servizio d’ordine e di disciplina, alla partenza con concetti più imparziali e sportivi, togliendo così quei piccoli nèi che possono aver fatto quest’anno a giusto titolo protestare qualcuno, senza però compromettere il successo e la riuscita della grandiosa e coraggiosa iniziativa bresciana.

Fotografica pagina 3 – 6

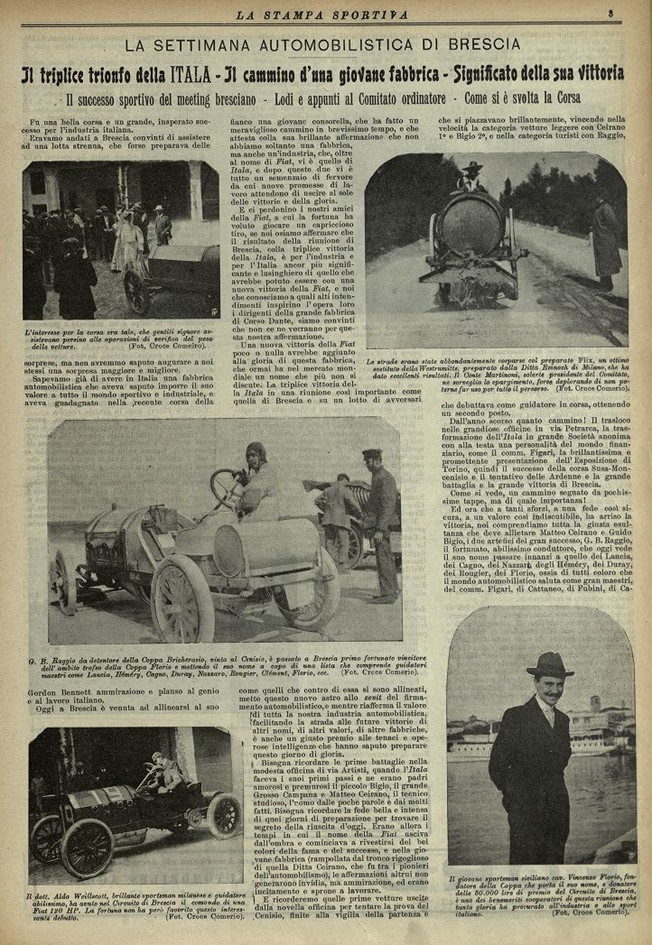

L’interesse per la corsa era tale, che gentili signore assistevano persino alle operazioni di verifica del peso delle vetture. (Fot. Croce Comeiro).

G. B. Raqgio da detentore della Coppa Bricherasio, vinta al Cenisio, è passato a Brescia primo fortunato vincitore d’eiv ambito trofeo della Coppa Florio e mettendo il suo nome a capo di una Usta che comprende guidatori maestri come Lancia, Héméry, Cagno, Duray, Nazzaro, Rougier, Clément, Florio, ecc. (Fot. Croce Comeno).

Il dott. Aldo Weillscott, brillante sportsman milanese e guidatore abilissimo, ha avuto nel Circuito di Brescia il comando di una Fiat 120 HE. La fortuna non ha però favorito questo interessante debutto. (Fot. Croce Comerio).

Le strade erano state abbondantemente cosparse col preparato Fiix, un ottimo sostituto della Westrumitte, preparato dalla Ditta Reinach di Milano, che ha dato eccellenti risultati. E Conte Martinoni, solerte presidente del Comitato, ne sorveglia lo spargimento, forse deplorando di non poterne far uso per tutto il percorso. (Fot. Croce Comerio).

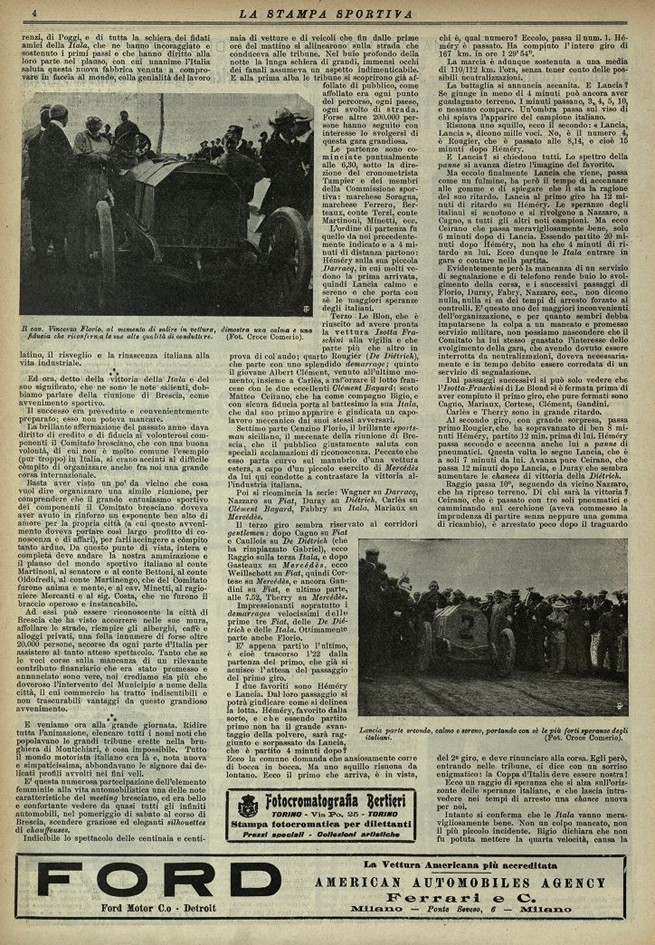

Il giovane sportsman siciliano cav. Vincenzo Florio, fondatiore della Coppa che porta il suo nome, e donatore delle 50.000 lire di premio del Curcuito di Brescia, e uno dei benemeriti cooperatori di questa riunione che tanta gloria ha procuratto all’industria e allo sport italiano (Fot. Croce Comerio)

Il cav. Vincenzo Florio, al momento di salire in vettura, dimostra una calma e una fiducia che riconferma le sue alte qualità di conduttore. (Fot. Croce Cornelio).

Lancia parte secondo, calmo e sereno, portando con sè le più forti speranze degli italiani. (Fot. Croce Comerio).

L’ordine non era certamente la nota dominante alla partenza, data tra una folla ingombrante di curiosi tollerati là dove erano stati esclusi coloro che per ragioni d’ufficio avrebbero dovuto esservi. (Fot. Croce Comerio).

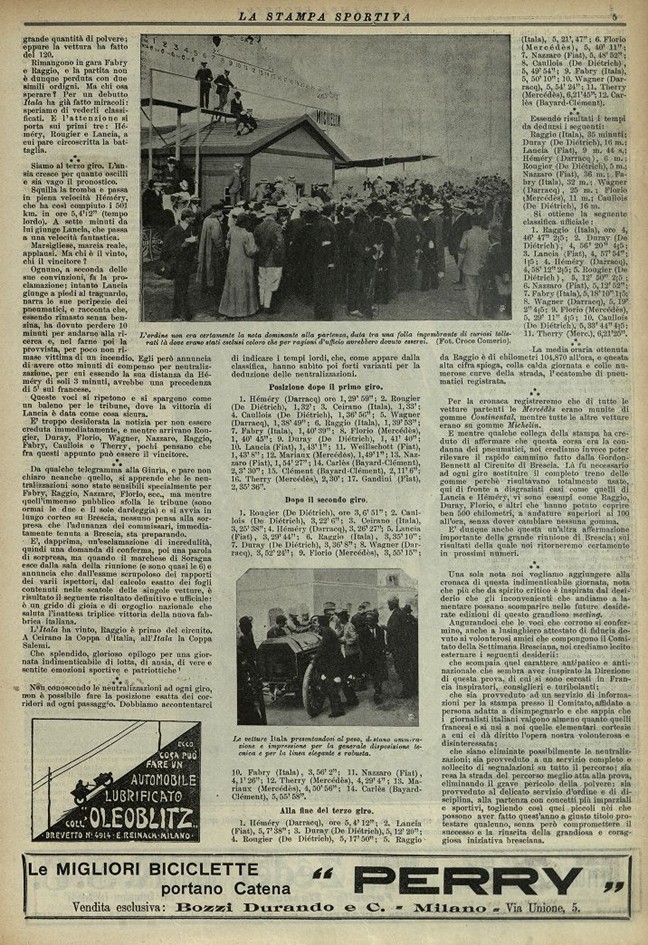

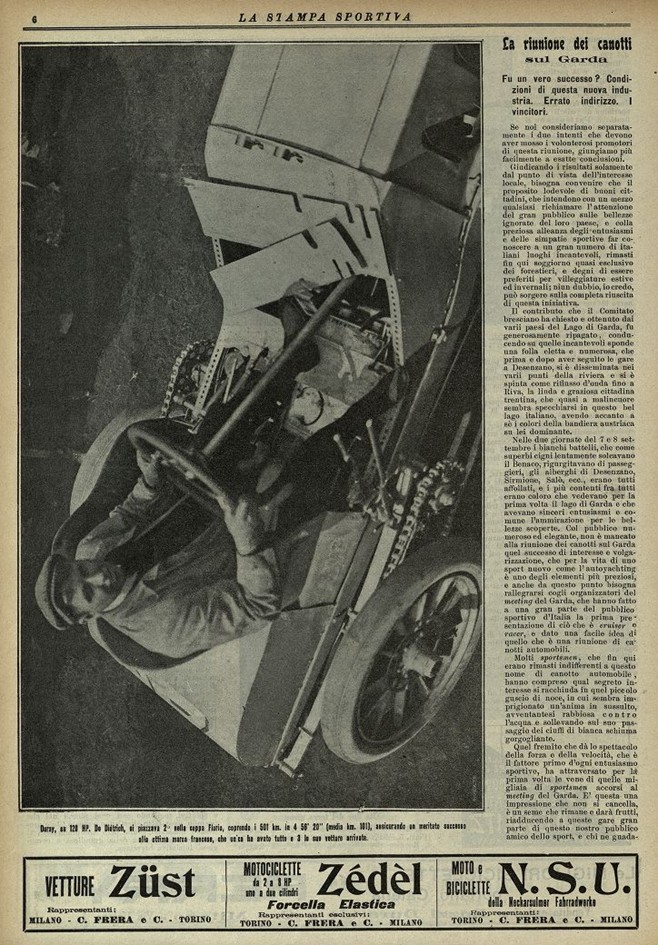

Duray, su 120 HP. Ds Dietrich, si piazzava 2″ nella coppa Florio, coprendo i 501 km. in 4 50′ 20″ (media km. 101), assicurando un meritato successo alla ottima marca francese, che unta ha avuto tutte e 3 le sue vetture arrivate.

Le vetture Itala presentandosi al peso, destano ammirazione e impressione per la generale disposizione tecnica e per la linea elegante e robusta.

********************

Translation by DeepL.com. My excuses for a very limited text-check of the original translation, as my knowledge of the Italian language is limited to the extent that it only helps me to survive summer holidays.

La Stampa Sportiva, Volume IV, No. 38, Torino, 17 September 1905

ITALA’s Triple Grand Victory in the BRESCIA Circuit.

Matteo Ceirano, winner of the Coppa d’Italia (Km. 300 in 2 40′ 48” hours).

Fabry secured the Coppa Conte di Salemi with his splendid ride (Km. 501 in 518′ 10” hours).

G. B. RAGGIO, first to arrive on the Brescia Circuit (Km. 501 in hours 4 46′ 47”, average 106 Km. per hour), in ITALA 100 HP car, Michelin pneus, Seren Rosso chassis, first holder of the Coppa Florio and winner of the L 50,000 prize.

THE BRESCIA AUTOMOBILE WEEK

ITALA’s triple triumph – The journey of a young factory – Significance of its Victory

The sporting success of the Brescian meeting – Praise and notes to the organizing committee – How the Race was run

It was a good run and a great, inspiring success for the Italian industry.

We had gone to Brescia, convinced that we would see a strenuous struggle, which perhaps would prepare surprises, but we could not have wished ourselves a greater and better surprise.

We already knew that we had in Italy an automobile factory, that had been able to impose its value on the entire sporting and industrial world and had earned in the recent Gordon Bennett race admiration and praise for Italian genius and work.

Today in Brescia, a young sister company has come to line up beside him, which has made a marvelous journey in a very short time, and which attests by its brilliant affirmation that we have not only a factory, but also an industry, that, in addition to the name of Fiat, there is that of Itala, and after these two there is a whole seedbed of fervor from which new promises of labor wait to come forth in the sunshine of victories and glory.

And may we forgive our friends at Fiat, on whom fortune has wished to play a capricious trick, if we dare to affirm that the result of the Brescia meeting, with Itala’s triple victory, is for industry and for Italy even more significant and flattering than it could have been with a new Fiat victory, and we who know to what lofty intentions the managers of the great factory in Corso Dante inspire their work, are convinced that they will not begrudge us this affirmation.

A new Fiat victory would have added little or nothing to the glory of this factory, which now has in the world market a name that is no longer in dispute. Itala’s threefold victory at a meeting as important as the one in Brescia and over such a lot of opponents as those who lined up against it, puts this new star at the zenith of the automotive firmament, and while it reaffirms the value of our entire automotive industry, facilitating the way for future victories of other names, other values, and other factories, it is also a just reward to the tenacious and industrious intelligences that have been able to prepare for this day of glory.

One has to remember the early battles in the modest workshop in Via Artisti, when Itala was taking its first steps and its loving and caring fathers were little Bigio, the great Grosso Campana and Matteo Ceirano, the studious technician, the man of few words and many deeds (Non parole ma fatti). One must remember the beautiful and intense faith of those days of preparation to find the secret of today’s success. Those were then the days when the name of Fiat was coming out of the shadows and beginning to clothe itself in the beautiful colors of fame and success, and in the young factory (sprouting from the luxuriant trunk of that Ceirano Firm, which was among the pioneers of motoring), the achievements of others did not generate envy, but admiration, and they were incitement and spur to work. And we will remember those first cars that came out of the fledgling workshop to attempt the Cenisio test, finished on the eve of the start and placed brilliantly, winning in the speed the light car category with Ceirano 1st and Bigio 2nd, and in the tourist category with Raggio, who was making his debut as a driver in the race, getting a second place.

Since last year how far have we come! The move to the grandiose workshops on Via Petrarca, the transformation of Itala into a large joint-stock company with a personality from the financial world at the head, such as Comm. Figari, the brilliant and promising presentation of the Turin Exposition, then the success of the Susa-Moncenisio race and the Ardennes attempt and the great battle and victory at Brescia.

As can be seen, a path marked by very few stages, but of what importance!

And now that to so many efforts, to such sure faith, to such unquestionable valor, victory has arisen, we understand all the righteous exultation that must cheer Matteo Ceirano and Guido Bigio, the two architects of the great success, G. B. Raggio, the fortunate, very skilful conductor, who today sees his name pass before that of the Lancias, the Cagnos, the Nazzarfc of the Héméry, the Dnray, the Rougier, the Florios, that is to say, of all those whom the motoring world hails as great masters, of comm. Figari, of Cattaneo, of Fubini, of Carenzi, of Poggi, and of the whole host of Itala’s trusted friends, who encouraged and supported its first steps and who are entitled to their share in the applause, with which unanimous Italy greets this new factory that has come to prove in the face of the world, with the genius of Latin work, the Italian awakening and rebirth to industrial life.

**

And now, having said something about the victory of the Itala and its significance, what are the salient points, we must talk about the Brescia meeting, as a sporting event.

Success was expected and conveniently prepared; it could not fail.

The brilliant success of last year gave credit and confidence to the willing members of the Brescia Committee, who with a good will, the example of which is not very common (unfortunately) in Italy, had set about the difficult task of organizing a great international race among us too.

One only has to have seen a little of what it means to organize such an event, to understand that the great enthusiasm for sport of the members of the Brescia Committee must have been reinforced by a high level of love for their city (which would benefit greatly from the increased awareness and business that would result from this event), to make them undertake such a difficult task. From this point of view, our admiration and the applause of the Italian sports world must go to Count Martinoni, Senator and Count Bettoni, Count Oldofredi, Count Martinengo, who were the soul and mind of the Committee, and to Cavaliere Minetti, Accountant Mercanti and Mr. Costa, who were its hard-working and tireless arm.

The city of Brescia can be grateful to them, as it saw an innumerable crowd of perhaps over 20,000 people flock to its walls, crowd the streets, fill the hotels, cafes and private lodgings, having come from all over Italy to witness the long-awaited spectacle. So much so that if the rumors about the lack of a significant financial contribution that had been promised and announced are true, we believe it is more than right that the Town Hall should intervene on behalf of the city, whose commerce has drawn indisputable and not insignificant advantages from this grandiose event.

* *

And now we come to the big day. It’s impossible to describe all the excitement, to list all the famous names that populated the grand stands erected on the Montichiari heath. The whole Italian motoring world was there and, a new and very pleasant note, there were lots of ladies with delicate profiles wrapped in fine veils.

This large participation of the female element in automotive life is one of the characteristic features of the Brescia meeting, and it was beautiful and comforting to see the graceful and elegant silhouettes of chauffeuses descending from almost all the endless cars on Saturday afternoon at the Brescia course. The sight of hundreds and hundreds of cars and vehicles lining the road leading to the stands from the early hours of the morning was indescribable. In the deep darkness of the night the long line of huge, immense headlights took on an unforgettable appearance. And at the first light of dawn the stands were already crowded with spectators, as crowded as every point along the route, every town, every bend in the road. Perhaps another 200,000 people followed the progress of this magnificent race with interest.

The race started on time at 6.30 a.m., under the direction of the timekeeper Tampier and the members of the Sports Commission: Marquis Soragna, Marquis Ferrerò, Berteaux, Count Terzi, Count Martinoni, Minetti, etc.

The starting order was the one we indicated previously and 4 minutes later the following started: Héméry in his little Darracq, which many see as the first to arrive, then Lancia calm and collected and who carries with him the greatest hopes of the Italians.

Third is Le Blon, who managed to have his Isotta Fraschini car ready on the eve of the race and who starts more than anything else in the car’s trial; fourth is Rougier (De Diétrich), who starts with a splendid demarrage; fifth is the young Albert Clément, who came at the last moment, together with Carlos, to strengthen the French lot with the two excellent Clément Bayards, sixth Matteo Ceirano, whose partner is Bigio, and with sure confidence brings his Itala to the starting line, which from its first appearance is judged a mechanical masterpiece by his own opponents.

Seventh is Cenzino Florio, the brilliant Sicilian sportsman, the patron of the Brescia meeting, who the public rightly greets with special cheers of gratitude. Too bad he’s leaving leaning on the handlebars of a foreign car, at the head of a small army of Mercedes he’s brought here to thwart the victory of Italian industry.

Then the series starts again: Wagner in the Darracq, Nazzaro in the Fiat, Duiay in the Diétrieh, Carlès in the Clément Bayard, Fabbry in the Itala, Mariaux in the Mercedes.

The third lap seems to be reserved for the gentlemen drivers: after Cagno in the Fiat and Caullois in the De Dietrich (replacing Gabriel), comes Raggio in the third Itala, and after Gasteaux in the Mercedes comes Weillschott in the Fiat, then Cortese in the Mercedes, and again Gandini in the Fiat, and last to start, at 7.52, Thery in the Mercedes.

The very fast demarrages of the first three Fiats, the De Dietrichs and the Italas are particularly impressive. Florio also gets off to a good start.

The last one has just started, that is, 22 laps have passed since the first one started, and the wait for the first lap to pass is already getting tense.

The two favorites are Héméry and Lancia. When they pass by, we’ll be able to judge how the race is shaping up. Héméry, favored by fate, and who, having started first, doesn’t have the great disadvantage of the dust, will be caught up to and overtaken by Lancia, who started 4 minutes later? This is the common question that anxiously runs from mouth to mouth. But a bell rings from afar. Here comes the first one, he’s in sight, who is it, number here? Here he is, number 1 is past. Héméry has passed. He has completed the entire 167 km lap in 1 hour 29 minutes and 54 seconds.

The pace is therefore sustained at an average of 110/112 km per hour, not taking into account possible neutralizations.

The battle promises to be fierce. What about Lancia? If he arrives in less than 4 minutes, he may still have gained ground. The minutes pass, 3, 4, 5, 10, and no one appears. A shadow passes over the face of those who were watching for the appearance of the Italian champion. A bell rings, and then a second: “Lancia, Lancia,” say a thousand voices. No, it’s number 4, it’s Rougier, who arrived at 8:14, 15 minutes after Héméry.

“And Lancia?” everyone wonders. The specter of a breakdown looms behind the image of the favorite.

But finally there he is, Lancia, coming, passing like a flash, but with time to mention the tires and explain that this is the reason for his delay. On the first lap Lancia is 12 minutes behind Héméry. The Italians‘ hopes are dashed and they turn to Nazzaro, Cagno, and all the other well-known champions. But here comes Ceirano, who is doing wonderfully well, only 6 minutes behind Lancia. Having started 20 minutes after Héméry, he is only 4 minutes behind him. So here come the Itala cars, joining the race and becoming a factor.

Evidently, however, the lack of a signaling service and telephone makes the progress of the race unclear, and the subsequent passages of Florio, Duray, Fabry, Nazzaro, etc., say nothing; nothing is known about the times of forced stops at the checkpoints. This is one of the major drawbacks of the organization, and although it seems that the blame should be attributed to a lack of promised military service, we cannot hide the fact that the Committee itself spoiled the interest of the race, which, having had to be interrupted by neutralizations, necessarily and in due course had to be accompanied by a signaling service.

From the following passages we can see that Le Blond’s Isotta-Fraschini stopped before completing the first lap, and that Cagno, Mariaux, Cortese, Clément and Gandini also stopped.

Carlès and Therry are very late.

In the second lap, to everyone’s surprise, Rougier takes the lead, having overtaken Héméry by a full 8 minutes, despite having set off 12 minutes before him. Héméry is second and also seems to be suffering from tire problems. This time Lancia is following him, only 7 minutes behind. Ceirano is also making progress, 12 minutes after Lancia, and Duray seems to be increasing Diétrich’s chances of victory.

Raggio is 10th, closely followed by Nazzaro, who has made up ground. Who will win? Ceirano, who had only three tires and was walking on the wheel rim (he had recklessly left without even a spare tire), stopped shortly after the finish line of the second lap and had to give up the race. However, as he entered the stands he told us with an enigmatic smile: the Italian Cup must be ours!

Here’s a ray of hope on the horizon of Italian hopes, and a glimpse that the time we’ve lost gives us a new chance.

Meanwhile, the Itala is doing wonderfully well. Not a single crash, not the slightest accident. Bigio declares that they couldn’t use fourth gear because of the large amount of dust; yet the car did 120 km/h.

With Fabry and Raggio still in the race, the game isn’t lost with two such machines. But who dares to hope? For a debut, Itala has already worked miracles; let’s hope we see them classified. And attention turns to the first three: Héméry, Rougier and Lancia, for whom the battle seems to be limited.

* *

We’re on the third lap. Anxiety grows as the oscillations increase and the prognosis becomes even more vague.

The horn sounds and Héméry passes at full speed, having covered the 501 km in 5 hours, 4 minutes and 2 seconds (gross time). Seven minutes behind him comes Lancia, who is traveling at a fantastic speed.

Marseillaise, royal march, applause. But who is the loser, who is the winner?

Each one, according to his convictions, makes the proclamation; meanwhile Lancia reaches the finish line on foot, tells of his adventures with the tires, and says that, having run out of gas, he lost 10 minutes looking for it and, while refueling, he almost caused a fire. However, he announced that he had eight minutes compensation for neutralization, so since his distance from Héméry was only 3 minutes, he would have a 5′ head start over the Frenchman.

These rumors spread like wildfire through the grandstands, where Lancia’s victory was considered a sure thing.

The news is too eagerly awaited not to be believed immediately, and while Rougier, Duray, Florio, Wagner, Nazzaro, Raggio, Fabry, Caullois and Therry arrive, few think that among these it could be the winner.”

* *

From some telegrams to the Jury, and it seems that even that is not clear, we learn that the neutralizations have been significant, especially for Fabry, Raggio, Nazzaro, Florio, etc., but while that immense audience is leaving the stands (it is now two o’clock and the sun is scorching) and setting off in a long procession for Brescia, no one is thinking about the surprise that the meeting of the commissioners, held immediately in Brescia, is preparing.

First there is an exclamation of disbelief, then a question for confirmation, then a word of surprise, but when the Marquis of Soragna leaves the meeting room (and it is almost 6 o’clock) and announces that from the scrupulous examination of the reports of the various inspectors, from the exact calculation of the sheets contained in the boxes of the individual cars, the following definitive and official result has been reached: it is a cry of joy and national pride that greets the unexpected triple victory of the new Italian factory.

Itala has won, Raggio is first on the circuit. Ceirano has won the Coppa d’Italia, Itala the Coppa Salemi.

What a splendid, glorious epilogue to an unforgettable day of struggle, anxiety, and true and heartfelt sporting and patriotic emotions.

* *

As we don’t know the neutralizations at each lap, it is not possible to determine the exact position of the riders at each passage. We must be content with indicating the gross times, which, as can be seen from the classification, have undergone significant variations due to the deduction of the neutralizations.

Position after the first lap.

1. Héméry (Darracq) 1 hour, 29 minutes, 59 seconds; 2. Rougier (De Diétrich), 1 hour, 32 seconds; 3. Ceirano (Itala), 1.33′; 4. Caullois (De Diétrieh), 1.36’56“; 5. Wagner (Darracq), 1.38’49”; 6. Raggio (Itala), 1.39’53“; 7. Fabry (Itala), 1.40’39”; 8. Florio (Mercédès), 1.40’45“; 9. Duray (De Diétrich), 1.41’40”; 10. Lancia (Fiat), 1.43’1“; 11. Weillschott (Fiat), 1.43‘ 8”; 12. Mariaux (Mercedes), 1.49’1“; 13. Nazzaro (Fiat), 1.54’ 27”; 14. Carlès (Bayard-Clément), 2.330“; 15. Clément (Bayard-Clément), 2.116”; 16. Therry (Mercédès), 2.30“; 17. Gandini (Fìat), 2.3536”.

After the second lap.

1. Rougier (De Dietrich), 3 hours, 6’51“; 2. Caullois (De Dietrich), 3 hours, 22’6”; 3. Ceirano (Itala), 3 hours, 25’38“; 4. Héméry (Darracq), 3 hours, 26’27”; 5. Lancia (Fiat), 3.29’44“; 6. Raggio (Itala), 3.35’10”; 7. Duray (De Diétrich), 3:36:08; 8. Wagner (Darracq), 3:52:24; 9. Florio (Mercédès), 3:55:15; 10. Fabry (Itala), 3:56:02; 11. Nazzaro (Fiat), 4.1’26“; 12. Therry (Mercédès), 4. 29’4”; 13. Mariaux (Mercédès), 4.50′ 56“; 14. Carlès (Bayard-Clément), 5. 55’58”.

At the end of the third lap.

1. Héméry (Darracq), 5 hours, 4 minutes, 12 seconds; 2. Lancia (Fiat), 5 hours, 7 minutes, 38 seconds; 3. Duray (De Diétrich), 5 hours, 12 minutes, 20 seconds; 4. Rougier (De Diétrich), 5 hours, 17 minutes, 50 seconds; 5. Raggio (Itala), 5, 21′, 47“; 6. Florio (Mercédès), 5, 40‘ 11”; 7. Nazzaro (Fiat), 5, 48′ 52“; 8. Caullois (De Diétrich), 5, 49’ 54”; 9. Fabry (Itala), 5. 50′ 10“; 10. Wagner (Darracq), 5, 54′ 24”; 11. Thery (Mercédès), 6.21’45”; 12. Carlès (Bayard-Clément).

**

The following times were deduced:

Raggio (Itala), 35 minutes; Duray (De Diétrich), 16 m.; Lancia (Fiat), 9 m. 44 s.; Héméry (Darracq), 6 m.; Rougier (De Diétrich), 5 m.; Nazzaro (Fiat), 36 m.; Fabry (Itala), 32 m.; Wagner (Darracq), 25 m.; Florio (Mercedes), 11 m.; Caullois (De Diétrich), 16 m.

The official classification is as follows:

1. Raggio (Itala), 4 hours, 46 minutes, 47 seconds 25; 2. Duray (De Diétrich), 4 hours, 56 minutes, 20 seconds 45; 3. Lancia (Fiat), 4 hours, 57 minutes, 54 seconds; 15; 4. Héméry (Darracq), 4, 58′ 12“ 25; 5. Rougier (De Diétrich), 5, 12′ 50” 2/5; 6. Nazzaro (Fiat), 5,12′ 52”; 7. Fabry (Itala), 5, 18′ 10“ 15; 8. Wagner (Darracq), 5, 19′ 2” 4(5; 9. Florio (Mercédès), 5, 29′ 11” 45; 10. Callois (De Diétrich), 5, 33′ 44“ 4/5; 11. Thery (Mercédès.), 6, 21’25”.

* *

The average speed obtained by Raggio was 104.870 kilometers per hour, and this high figure, together with the hot day and the numerous bends in the road, explains the carnage of tires recorded.

**

For the record, we’ll note that of all the cars that started the race, the Mercedes were equipped with Continental tires, while all the other cars were on Michelin tires.

And while some colleagues from the press thought they were stating that this race was the condemnation of tires, we believe instead that we can see the rapid progress made by the Gordon-Bennett at the Brescia Circuit. There it was necessary to replace the entire set of tires after every lap because they were completely worn out. Here, in contrast, in contrast to unfortunate cases such as those of Lancia and Héméry, there are examples such as Raggio, Duray, Florio, and others who were able to cover 500 kilometers at speeds of over 100 kilometers per hour without having to change any tires.

This is therefore another important result of the great meeting in Brescia; we will certainly be discussing the results in future issues.

* *

We would like to add just one note to the report of this unforgettable day, a note that is inspired more by the desire for the inconveniences we are about to complain on disappearing in future editions of this grandiose meeting, than by a critical spirit.

Hoping that the rumors are true, and as a flattering vote of confidence to the willing friends who make up the Committee of Settimana Bresciana, we believe it is legitimate to express the following wishes:

That the unpleasant and anti-national character that seems to have inspired the management of this event, for which they sought inspiration, advice and tribulation in France, disappears.

that an information service for the press be provided at the Committee, entrusted to a suitable person who knows that Italian journalists are worth at least as much as French ones, and that we be shown the basic courtesy to which our willing and disinterested work entitles us;

that neutralizations are eliminated if possible; that a complete and prompt service of reports is provided along the entire route; that the road along the route is made more suitable for the trial, eliminating the serious danger of dust; that the delicate service of order and discipline is provided, at the start with more impartial and sporting concepts, thus removing those small obstacles that may have rightly caused someone to protest this year, without compromising the success and outcome of the grandiose and courageous Brescian initiative.

Fotos pages 3 – 6

The interest in the race was such that kind ladies even assisted in the operations of verifying the weight of the cars. (Photo Croce Comeiro).

G. B. Raggio, from being the holder of the Bricherasio Cup, won at Cenisio, went to Brescia as the first lucky winner of the coveted Florio Cup trophy and put his name at the head of a team that included master drivers such as Lancia, Héméry, Cagno, Duray, Nazzaro, Rougier, Clément, Florio, etc. (Photo: Croce Comeno).

Dr. Aldo Weillscott, a brilliant sportsman from Milan and a very skilled driver, was in command of a Fiat 120 HE on the Brescia Circuit. However, luck did not favor this interesting debut. (Photo: Croce Comerio).

The roads had been generously sprinkled with Fiix, an excellent substitute for Westrumitte, prepared by the Reinach Company of Milan, which gave excellent results. And Conte Martinoni, the diligent president of the Committee, supervises the spreading, perhaps regretting that he cannot use it for the whole route. (Photo Croce Comerio).

The young Sicilian sportsman, Vincenzo Florio, founder of the Cup that bears his name, and donor of the 50,000 lire prize for the Brescia Circuit, is one of the worthy collaborators of this meeting that has brought so much glory to Italian industry and sport (Photo: Croce Comerio).

Mr. Vincenzo Florio, as he gets into the car, shows calmness and confidence that reconfirms his high qualities as a driver. (Photo: Croce Cornelio).

Lancia starts second, calm and serene, carrying with him the highest hopes of the Italians. (Photo: Croce Comerio).

Order was certainly not the dominant note at the start, given among a cumbersome crowd of tolerated onlookers where those who, for official reasons, should have been there were excluded. (Photo Croce Comerio).

Durai, on 120 HP. Ds Dietrich, placed 2nd in the Florio cup, covering the 501 kilometers in 4 hours 50 minutes 20 seconds (average speed 63 miles per hour), ensuring a well-deserved success for the excellent French make, which had all 3 of its cars finish. The Itala cars, when presented for weighing, arouse admiration and make an impression due to their general technical arrangement and their elegant and robust lines.