Text and jpegs by courtesy of hathitrust.org www.hathitrust.org, compiled by motorracinghistory.com

MOTOR AGE Vol. XXV, No. 23 Chicago, June 4, 1914

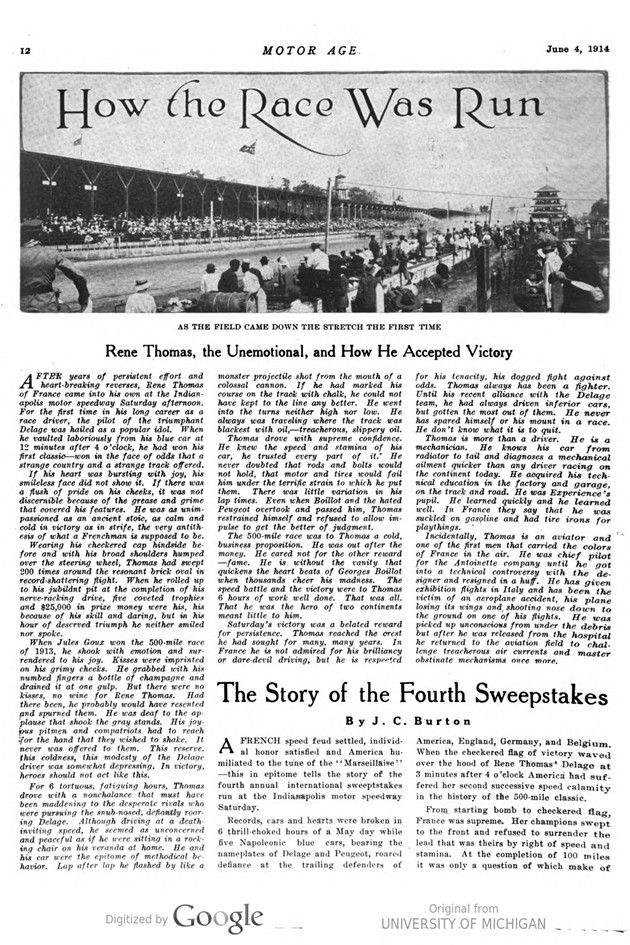

How the Race Was Run

Rene Thomas, the Unemotional, and How He Accepted Victory

AFTER years of persistent effort and heart-breaking reverses, Rene Thomas of France came into his own at the Indianapolis motor speedway Saturday afternoon. For the first time in his long career as a race driver, the pilot of the triumphant Delage was hailed as a popular idol. When he vaulted laboriously from his blue car at 12 minutes after 4 o’clock, he had won his first classic – won in the face of odds that a strange country and a strange track offered.

If his heart was bursting with joy, his smileless face did not show it. If there was a flush of pride on his cheeks, it was not discernible because of the grease and grime that covered his features. He was as unimpassioned as an ancient stoic, as calm and cold in victory as in strife, the very antithesis of what a Frenchman is supposed to be.

Wearing his checkered cap hindside be- fore and with his broad shoulders humped over the steering wheel, Thomas had swept 200 times around the resonant brick oval in record-shattering flight. When he rolled up to his jubilant pit at the completion of his nerve-racking drive, five coveted trophies and $25,000 in prize money were his, his because of his skill and daring, but in his hour of deserved triumph he neither smiled nor spoke.

When Jules Goux won the 500-mile race of 1913, he shook with emotion and sur- rendered to his joy. Kisses were imprinted on his grimy cheeks. He grabbed with his numbed fingers a bottle of champagne and drained it at one gulp. But there were no kisses, no wine for Rene Thomas. Had there been, he probably would have resented and spurned them. He was deaf to the applause that shook the gray stands. His joyous pitmen and compatriots had to reach for the hand that they wished to shake. It never was offered to them. This reserve, this coldness, this modesty of the Delage driver was somewhat depressing. In victory, heroes should not act like this.

For 6 tortuous, fatiguing hours, Thomas drove with a nonchalance that must have been maddening to the desperate rivals who were pursuing the snub-nosed, defiantly roaring Delage. Although driving at a death-inviting speed, he seemed as unconcerned and peaceful as if he were sitting in a rocking chair on his veranda at home. He and his car were the epitome of methodical behavior. Lap after lap he flashed by like a monster projectile shot from the mouth of a colossal cannon. If he had marked his course on the track with chalk, he could not have kept to the line any better. He went into the turns neither high nor low. He always was traveling where the track was blackest with oil – treacherous, slippery oil.

Thomas drove with supreme confidence. He knew the speed and stamina of his car, he trusted every part of it. He never doubted that rods and bolts would not hold, that motor and tires would fail him under the terrific strain to which he put them. There was little variation in his lap times. Even when Boillot and the hated Peugeot overtook and passed him, Thomas restrained himself and refused to allow im- pulse to get the better of judgment.

The 500-mile race was to Thomas a cold, business proposition. He was out after the money. He cared not for the other reward -fame. He is without the vanity that quickens the heart beats of Georges Boillot when thousands cheer his madness. The speed battle and the victory were to Thomas 6 hours of work well done. That was all. That he was the hero of two continents meant little to him.

Saturday’s victory was a belated reward for persistence. Thomas reached the crest he had sought for many, many years. In France he is not admired for his brilliancy or dare-devil driving, but he is respected for his capacity, his dogged fight against odds. Thomas always has been a fighter. Until his recent alliance with the Delage team, he had always driven inferior cars, but gotten the most out of them. He never has spared himself or his mount in a race. He don’t know what it is to quit.

Thomas is more than a driver. He is a mechanician. He knows his car from radiator to tail and diagnoses a mechanical ailment quicker than any driver racing on the continent today. He acquired his technical education in the factory and garage, on the track and road. He was Experience’s pupil. He learned quickly and he learned well. In France they say that he was suckled on gasoline and had tire irons for playthings.

Incidentally, Thomas is an aviator and one of the first men that carried the colors of France in the air. He was chief pilot for the Antoinette company until he got into a technical controversy with the de- signer and resigned in a huff. He has given exhibition flights in Italy and has been the victim of an aeroplane accident, his plane losing its wings and shooting nose down to the ground on one of his flights. He was picked up unconscious from under the debris but after he was released from the hospital, he returned to the aviation field to challenge treacherous air currents and master obstinate mechanisms once more.

The Story of the Fourth Sweepstakes

By J. C. Burton

A FRENCH speed feud settled, individual honor satisfied and America humiliated to the tune of the „Marseillaise“ -this in epitome tells the story of the fourth annual international sweepstakes run at the Indianapolis motor speedway Saturday.

Records, cars and hearts were broken in 6 thrill-choked hours of a May Day while five Napoleonic blue cars, bearing the nameplates of Delage and Peugeot, roared defiance at the trailing defenders of America, England, Germany, and Belgium. When the checkered flag of victory waved over the hood of Rene Thomas‘ Delage at 3 minutes after 4 o’clock America had suffered her second successive speed calamity in the history of the 500-mile classic.

From starting bomb to checkered flag, France was supreme. Her champions swept to the front and refused to surrender the lead that was theirs by right of speed and stamina. At the completion of 100 miles it was only a question of which make of French car, Delage or Peugeot, would tri- umph. Early in the race it was evident that American cars were doomed to defeat. When Thomas rolled up to the pits a victor only six of America’s defenders were running and two of these were outside the money. Thirteen cars that carried the colors of Uncle Sam stood silent at the pits and in the infield or lay on the rim of the red saucer, eliminated by mechanical faults or accidents.

Even at 10 o’clock in the morning America was skeptical but determined. For speed, her cars were outclassed. This had been proven by Goux and Boillot in practice spins and the elimination trials. Her hope of victory lay in the stamina of her defenders, on bolts and rods that might be made of sturdier stuff than those of the invading mechanisms. It was a vain hope.

American Cars Lead Twice

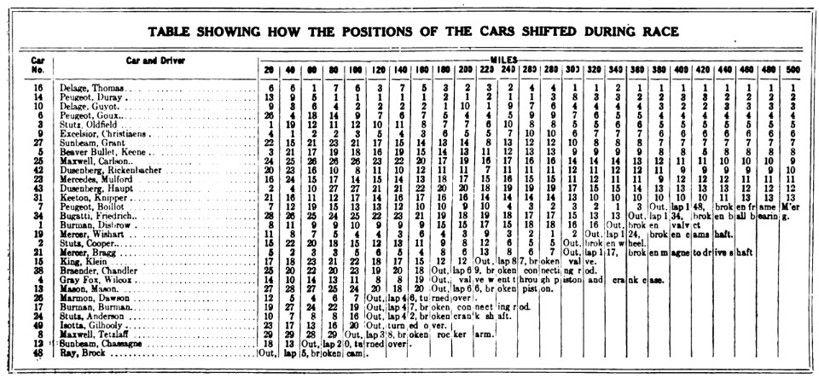

At only two stages during the race was an American car in front. When the first eight laps had been turned Barney Oldfield was setting the pace in the No. 3 Stutz but at the completion of another 20 miles he had surrendered this position to Christiaen’s Excelsior. Americans had another opportunity to cheer when it was announced that Wishart and the Mercer were leading at the end of 280 miles. With these two exceptions the foreigners showed the way. Christiaens was in front at the completion of 40 miles and then started to drop back, fearing to attempt high speed on the slippery track with a car that had no differential. Thomas shot to the front at the completion of 60 miles but was passed in the next 20-mile stage by Duray who led up to the 160-mile mark.

For the next 60 miles Guyot and Duray alternated in holding the position of ad- vantage, the driver of the No. 10 Delage leading at the completion of 180 and 220 miles and the pilot of the mechanical baby showing the way at 200 miles. The field took Duray’s smoke from the 220 to the 280-mile post, when Wishart passed the holder of the flying kilometer record. Thomas led at the end of 300 and 320 miles to drop back behind the desperately driving Boil- lot in the Peugeot at 340 miles.

When the twice-crowned grand prix victor was eliminated with a broken frame on the one hundred and forty-eighth lap Thomas again thundered into the lead, never to be overtaken by the speed merchants in the rear.

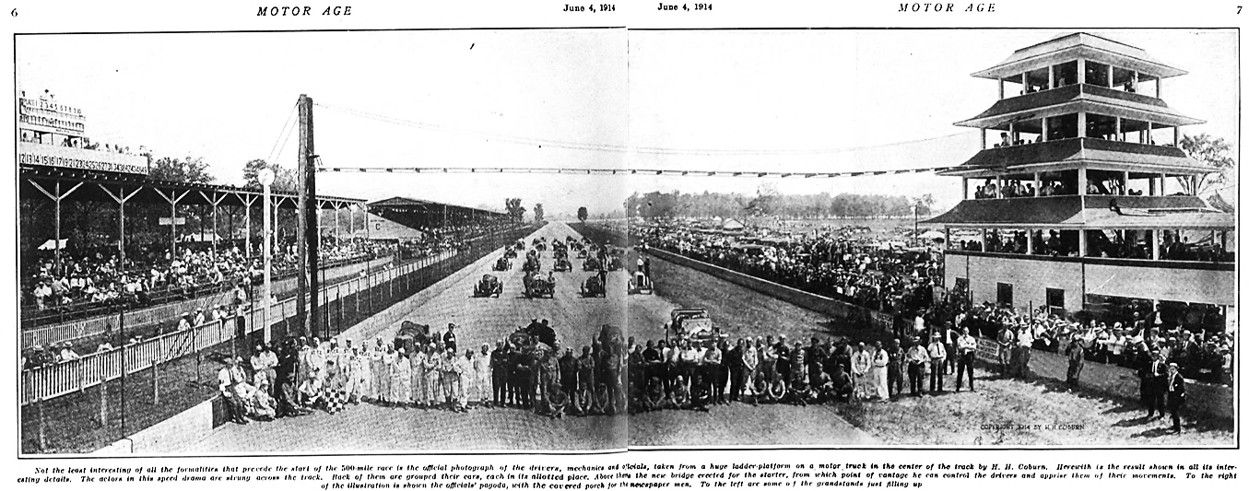

At 9:45 o’clock a flotilla of varicolored space gourmands had been marshalled at the starting line. Six nations were represented – France by three Peugeots and two Delages; England, by two black, cigar-shaped Sunbeams; Belgium, by the orange Excelsior; Germany, by the diminutive Bugatti and Mulford’s Mercedes equipped with a Peugeot motor; Italy by the green Isotta, and the United States by three white Stutzes, two yellow Mercers, two red, white and blue striped Duesenbergs, two blue Burmans, the red Keeton, two black Maxwells, the Gray Fox, the Beaver Bul- let, the King, Dawson’s Marmon, the Braender Bulldog and the Ray. The Isotta was allowed to start at the proverbial eleventh hour when Dalph DePalma decided to withdraw his Mercedes, after coming to the conclusion that the aviation engine which it carried would not with- stand the terrific vibration to which it would be submitted. Pullen’s Mercer had turned a faster lap in the elimination trials than the Italian entry but the 1914 grand prize victor refused to start.

The thirty cars were lined up in seven rows in the following order:

First row – Chassagne’s Sunbeam, Tetzlaff’s Maxwell and Wilcox’s Gray Fox.

Second row – Chandler’s Braender Bull Dog, Carlson’s Maxwell, Mulford’s Mercedes and Christiaen’s Excelsior.

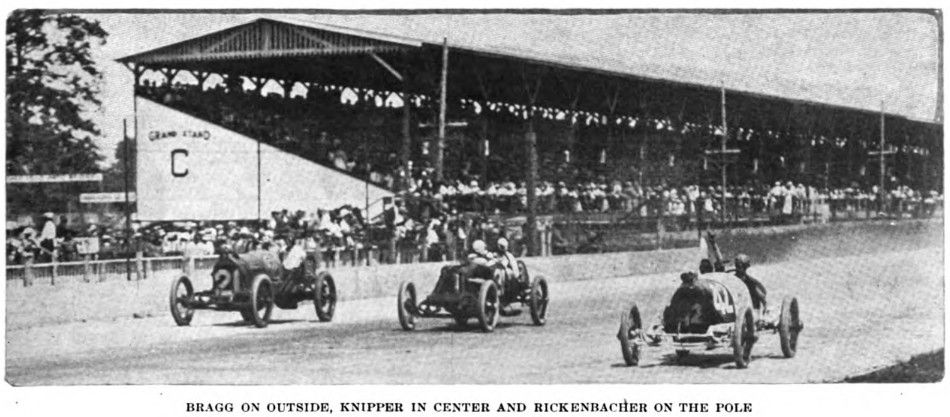

Third row – Klein’s King, Bragg’s Mercer, Duray’s Peugeot, Guyot’s Delage and Knipper’s Keeton.

Fourth row – Mason’s Mason, Cooper’s Stutz, Thomas‘ Delage, Anderson’s Stutz and Daw- son’s Marmon.

Fifth row – Freidrich’s Bugatti. Goux’s Peugeot, Gilhooley’s Isotta, Brock’s Ray and Burman’s Burman.

Sixth row – Rickenbacher’s Duesenberg, Disbrow’s Burman, Wishart’s Mercer, Grant’s Sunbeam and Keene’s Beaver Bullet.

Seventh row – Haupt’s Duesenberg, Boillot’s Peugeot and Oldfield’s Stutz.

Race Starts Promptly at Ten

Promptly at 10 o’clock the starting bomb exploded, and the roaring field was sent away with Carl Fisher setting a 60-mile an After the completion of the hour pace. preliminary lap and when the president of the speedway turned off the track, thirty drivers stepped on as many throttles, the motors‘ roar became more menacing, the smoke of the exhausts more dense and the fourth annual 500-mile race was on.

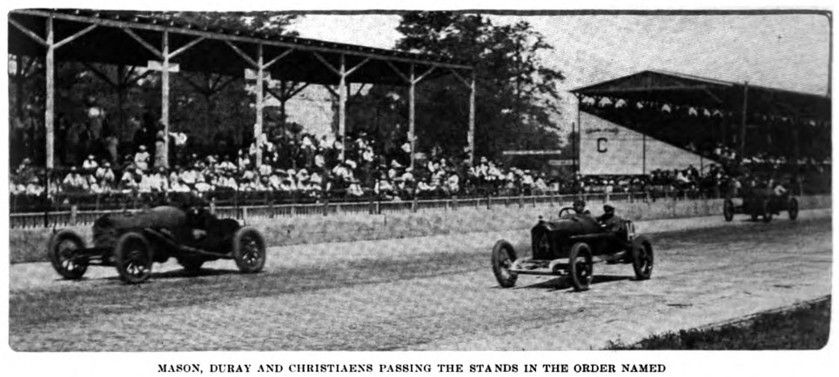

Favored by his position in the first row, Howdy Wilcox in the Gray Fox shot over the wire in the lead at the completion of the first lap. The other cars were well bunched and were caught in the following order: Christiaen’s Excelsior, Carlson’s Maxwell, Tetzlaff’s Maxwell, Chassagne’s Sunbeam, Bragg’s Mercer, Mulford’s Mercedes, Goux’s Peugeot, Duray’s Peugeot, Thomas‘ Delage, Chandler’s Braender, Guyot’s Delage, Knipper’s Keeton, Daw- son’s Marmon, Klein’s King, Cooper’s Stutz, Freidrich’s Bugatti, Mason’s Ma- son, Burman’s Burman, Wishart’s Mercer, Grant’s Sunbeam, Gilhooley’s Isotta, Bl- lot’s Peugeot, Rickenbacher’s Duesenberg, Disbrow’s Burman, Keene’s Beaver Bullet, Haupt’s Duesenberg and Oldfield’s Stutz.

At the completion of the second lap the Gray Fox had dropped back to fourth place and Christiaens was leading with the Max- wells 300 yards behind him. On the next circuit of the track Wishart moved up to second place but the Mercer did not challenge the pacemaker for long as Goux could not restrain his natural impetuosity. and had brought the Peugeot up within 200 yards of the leading Belgian at the 10-mile mark.

Ray First Car Eliminated

One car, Brock’s Ray, was eliminated before the first 20 miles had been covered, being docked with a broken cam on its fifth lap. Christiaens looked to have a world of speed on his first four circuits of the oval and there was a cry of surprise from the stands when it was announced that Barney Oldfield had come out from the ruck and was leading at the end of 20 miles. Christiaens, however, passed the Stutz and was in front at the completion of 40 miles. When this stage of the race was reached misfortune had laid its hand on another entry, Chassagne’s Sunbeam blowing a tire on the turn, dishing a wooden wheel and turning over. The idol of Brooklands was not seriously hurt, although he was escorted by Gaston Morris to the hospital tent, where a few beauty patches were applied to some cuts on his face.

A coming event cast its shadow before it when 60 miles had been covered, Rene Thomas and the Delage hurtling to the front at this stage of the struggle. The predestined victor’s time for the twenty- four laps was 38 minutes 52 seconds, an average speed of 83.6 miles per hour. The tiny Peugeot, however, was a most persistent challenger and trailed but 19 seconds behind the pacemaker.

Tiny Peugeot Passes Delage

In the next 20 miles Duray not only over- took Thomas but passed the Delage and went to the front to play the role of a mechanical David and humiliate the trailing Goliaths of speed for thirty-two circuits of the track. With the small Peugeot setting the pace, Guyot in the No. 10 Delage took upon himself the task of clinging to Duray, Thomas dropping back to seventh place when he stopped at the pits for the first time to change a tire. This stop did not prove costly, however. Thomas gradually crept up on the Peugeot and although he did not pass it until the two hundred and fortieth mile was turned was always in a dangerous position. Duray completed 100 miles in 1 hour, 10 minutes, 46 seconds, an average speed of 85 miles an hour.

Teddy Tetzlaff joined Ray and Chassagne as spectators after completing thirty-eight laps, a broken rocker arm eliminating his Maxwell just before it had completed one-fifth of the strenuous journey over the slippery bricks.

Disaster strode out on the track soon after the first 100 miles of the race had been covered. An accident on the turn, resulting from the blowing of a tire and the overturning of the Isotta, not only eliminated the Italian entry but wrecked Dawson’s Marmon and forced Gil Anderson to retire the No. 24 Stutz with a broken crankshaft. Of the six participants in the crash only Anderson and his mechanician escaped without injury. Bob Burman also retired the No. 17 Burman at this stage of the race with a broken connecting rod but continued his chase of the haughty Frenchmen in the Keeton, relieving Billy Knipper, the regular driver.

Guyot Shoots to the Front

After holding the lead for over 80 miles, Duray dropped back in favor of Guyot, who passed the diminutive Peugeot shortly before the 180-mile mark was reached. The Delage driver covered this distance in 2 hours 7 minutes 20 seconds. Duray proved as persistent a challenger as he had been a pacemaker and in the next eight circuits of the track overtook Guyot and led at the completion of 200 miles.

Before the 200 miles had been covered three more American cars had been eliminated. Mason retired the Mason with a broken piston on the sixty-sixth lap, a valve went through the piston and crank-case of the Gray Fox and forced Wilcox to abandon the race, and Chandler docked the Braender Bulldog with a broken connecting rod after covering sixty-nine laps.

At the end of 220 miles Guyot again had passed Duray but he soon lost the commanding position when forced to stop at the pits and the small blue car was leading the field once more when 240 miles had been covered. Another American contender was eliminated while Guyot and Duray were playing Alphonse and Gaston and alternating in setting the pace, Klein abandoning the King on the eighty-seventh lap with a broken valve.

Georgas Boillot, favorite in the betting, experienced more than his share of tire trouble in the early stages of the race but by desperate driving and great bursts of speed gradually worked up from the position of trailer to challenger and at the end of 240 miles was in fourth place and gaining steadily on the small Peugeot and the two Delages.

Thomas Leads at 250 Miles

Thomas was again in front when the race was half over with Boillot only a few seconds behind. They had a 1-lap lead on Wishart and Duray, while two laps behind were Bragg and Guyot, running in fifth and sixth positions respectively.

At 260 miles Duray was leading the field with Wishart second, Boillot third, Thomas fourth and Bragg fifth, the driver of the small Peugeot passing both Boillot and Thomas when both were forced to stop at the pits for tire changes.

For the first time in the race since Old- field led at the 20-mile mark, an American car was in front when Wishart completed 280 miles. The Mercer had very few seconds to spare, however, with Boillot giving desperate pursuit and gaining at every revolution of his car’s wheels. Wishart’s time for the 280 miles was 3 hours, 24 minutes, 4 seconds and Boillot was trailing but 24 seconds behind the yellow pacemaker.

Thomas and the Delage were also in a commanding position and by a sensational burst of speed succeeded in sweeping to the front and taking the Prest-O-Lite trophy offered to the leader at 300 miles. Wishart was second and Boillot third at this stage of the race. Two more American cars had been eliminated, Bragg’s Mercer with a broken driveshaft magneto on the one hundred and seventeenth lap, and Cooper’s Stutz with a broken wheel on the one hundred and nineteenth lap.

The terrific speed demanded by Wishart of the Mercer was costly. A broken cam- shaft forced him to abandon the race on the one hundred and twenty-fourth lap and left Boillot on the track alone to give battle to the persistent Delage. Boillot was destined to meet the same fate as Wishart after he had wrested the lead from Thomas at the completion of 340 miles. The Peugeot blew a tire on the far turn and the grand prix victor, in conquering his plunging car, broke a frame member that forced him to retire to the seclusion of his pit, from where he watched the futile attempts of his teammate Goux to overtake the despised Delages.

Just before Boillot retired in disgust two American cars were docked permanently. Disbrow retired the No. 1 Burman with broken connecting rods and Freidrich, the lone German representative, abandoned the Bugatti with a broken ball bearing on the driving pinion.

Delage Romps Home

With Boillot eliminated, Rene Thomas had the race as good as won. After going into the lead at the completion of 360 miles he was never challenged or overtaken. In the remaining 140 miles of his record-breaking flight he increased his lead over Duray’s Peugeot from 1 minute, 22 seconds to 6 minutes and 19 seconds.

At the 480-mile mark Guyot passed the small Peugeot and went into second place but held this position for only 16 laps before he was forced to bow before the speed of Duray’s diminutive mount.

For the last 100 miles of the race Goux was firmly entrenched in fourth place. Old- field, more than 4 minutes behind the 500- mile race winner of 1913, was powerless to overtake the blue car, although he drove desperately and was not forced to stop.