TText and jpegs by courtesy of hathitrust.org www.hathitrust.org, compiled by motorracinghistory.com

MOTOR AGE Vol. XXV, No. 22 Chicago, May 28, 1914

The History of the Indianapolis Sweepstakes

Among the noisy thousands that will pack the gray stands of the Indianapolis motor speedway Saturday, there will be one inconspicuous patriarch, one silent and nonchalant figure who will yawn and stretch all through the thrill-choked day and murmur over and again to himself „Old stuff“ as the cars roar by in monotonous and death-defying flight.

You may not be able to find him without a search warrant. One minute he will be waiting for something ominous to happen on an oil-soaked embankment; the next, lounging near some pit where driver, mechanic and helpers, grimy and toiling, are cursing the loss of seconds; then you may see him on the glaring red straightway where two contenders for a fortune are racing for the lead. He will be here, there, everywhere – for he is a privileged character and passes cautious officials and khaki-clad guardsmen without being challenged.

Provided you are able to interrupt his ceaseless perambulations and can force him to submit to an interview, he will relate some reminiscences that will make you forget that Boillot is leading dePalma by 27 seconds – if he is – and that Duray has stopped on the fifty-first lap to change a right rear – if he has.

This old man of the speedway measures his experiences by centuries, not years. Five hundred years before the dawn of the Christian era, he stood on the sacred plains of Olympus, among the temples and statues of the gods and the treasure houses of the Greeks, and watched the lithe-limbed youths of Sparta, Athens, Thebes and Corinth run, wrestle, box and throw the discus for priceless laurel wreaths and the favor of the attending but unseen divinities.

During the reign of the profligate Caesars, he mingled with the throngs in the circus maximus of Rome. He saw the sword of Spartacus crash through the steel helmet and skull of a fellow gladiator of Capua; saw Ben Hur and his Arabian steeds emerge from the dense dust of the amphitheater victors in the chariot race; saw the giant Ursus throw the maddened bull; saw the blood of Christian martyrs stain red the floors of the lion’s cage. He stood at the side of Nero, saw the Emperor turn down his fat thumbs, touched his purple toga.

When Richard the Lion Hearted sat upon the throne of England, he watched Ivanhoe ride out upon the field of honor; saw lances shivered and knights unhorsed in the tournaments of the Middle Ages; heard the despairing shrieks or exultant cries of fair ladies as they beheld the overthrow or victory of their champions.

In the gay arenas of Seville and Madrid, he has viewed the polychromatic processions of brightly caparisoned picadors and matadors; beheld the goring of horses and the death quivers of a defeated bull; saw the cheeks of a Carmen flush with pride and passion as she kissed the lips of her triumphant Don Juan.

Old stuff! Of course, all this strife, this clamor, this crowd, this excitement is old stuff to him, but without him the 500-mile race would be only a scientific test of the stamina of mechanism and the skill of man. He is Spectacle. His presence at the speedway is imperative. In color and thrills, the richest of all speed classics ranks with the Olympic games of Greece, the gladiatorial combats of Rome, the knightly jousts of medieval England and the bull fights of Spain. He has made it so.

The 500-mile race is more than a contest. It is a pageant of motion, a spectacle of action, a fete of frenzy and a melodrama of speed. It is color, excitement, uncertainty, despair and triumph crowded into 7 hours of a red May day. It has its heroes, crowned and uncrowned, – drivers who are as great in defeat as others are in victory. It abounds in what the writer calls features, what the artist terms high lights. To prove the truth of such assertions, we have only to beat back on the trail of memory 3 years and view in retrospect the Homeric struggles of 1911, 1912 and 1913.

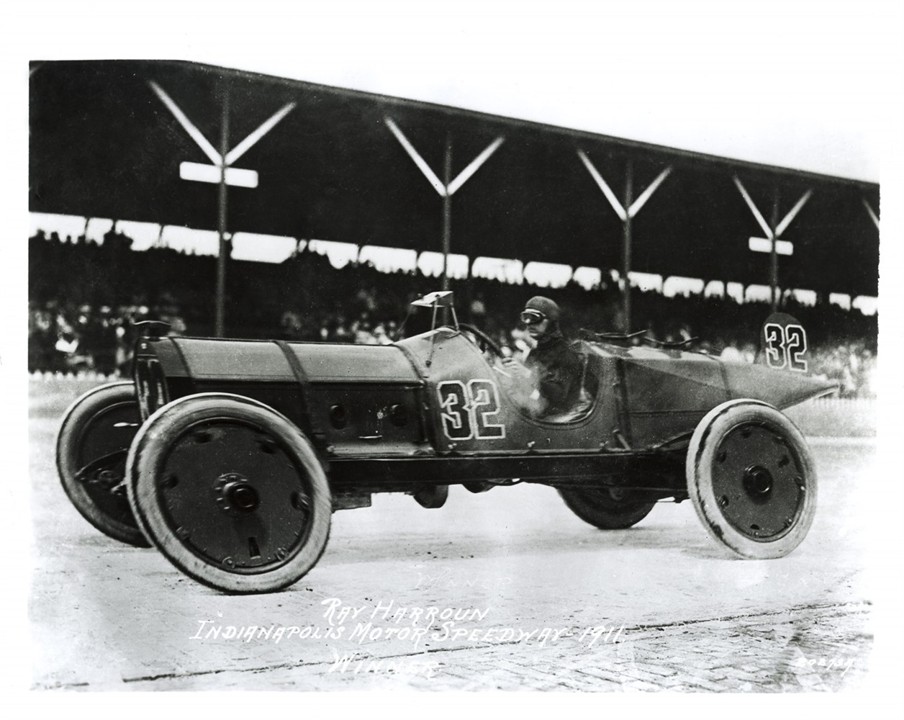

IN the race of 1911, the first 500-mile contest held on the speedway and featured by the closest finish in the annals of the three classics, Ralph Mulford learned the exact value of a second. In his days as a schoolboy he had scrawled in his copybook „Seconds are precious,“ but just how precious he never knew until that Memorial Day afternoon of 3 years ago. Then each second was worth to him just $48.54% in the coin of the realm.

Harroun’s Eye-lash Victory

Ray Harroun, the winner, flashed across the wire in the Marmon only 4 minutes 43 seconds before Starter Wagner flecked the hood of Mulford’s Lozier with the checkered flag. On corrected time, however, Harroun’s lead was reduced to 1 minute and 43 seconds. Less time than it takes the second hand of your watch to make two revolutions, one eight hundred and thirty-ninths of a fleeting day, cost Mulford the victory and deducted $5,000 from his winnings. In the history of motor car racing in America, there is but one triumph by a narrower margin and that was the victory of David Bruce-Brown in the American grand prize of 1910, when he defeated Hemery by 1.42 seconds in the most spectacular finish of all time.

Where were those precious seconds lost in the 500-mile race of 1911? Probably at the pit, for Mulford was the prey of the blowout jinx all during the contest and changed no fewer than fourteen tires before he completed his exasperating 5-century flight while Harroun stopped for new rubber but three times. Defeat changed Mulford’s perpetual smile to a temporary frown on the hundred and ninety-third lap, when the Lozier driver was chasing Harroun like a madman in an attempt to overtake and pass the flying Bedouin in the seven more circuits of the track that each had to make. In this crisis, Mulford rolled up to his pit on three castings and the straightening of a rim and the putting on of a tire cost him 22 minutes, a loss that never regained although Smiling Ralph again took up the pursuit in the vain hope that Harroun might be forced to stop before the end.

The hero, the victor, the whirling dervish of this race, Harroun, drove neither sensationally nor spectacularly. Riding without a mechanician, he made of the contest a cold business proposition. He was more cautious than daring. He merely decided on a pace and maintained it religiously. Instead of rushing to the front at the very start, he was content to lay back in the ruck and await his opportunity. His seeming phlegmatism was almost nerve-racking to the crowds in the stands, to whom the Marmon looked like a huge yellow wasp crawling about the rim of a huge red saucer.

Patschke Goes to the Front

Some of the credit for the Marmon victory – how much still is a matter of dispute – justly belongs to Cyrus Patschke. Patschke drove only 100 miles of the race, but made the most of his opportunity. Relieving Harroun at the completion of the sixty-fourth lap, he stepped upon the throttle of the Marmon and gave relentless chase to Bruce-Brown in the pace-making Fiat. Impetuous where Harroun was cautious, Patschke overtook the Italian speed creation and shot to the front, taking a lead that Harroun never surrendered when he again took the wheel of the yellow car.

The 1911 race was the only one of the three marked by a fatal accident. Samuel Dickson, mechanic for Arthur Greiner, met death early in the contest when the Amplex threw a rim and tire on the back stretch and turned turtle. Among the drivers, the Amplex was regarded as the hoodoo car. In practice, it had run wild and crashed into a concrete wall, breaking Joe Horan’s leg.

Another accident, not as serious but one that sent a greater thrill through the spectators, occurred in the home stretch and rendered one driver and two mechanics hors du combat. Jagersberger, in the Case, was running slowly in the middle of the track opposite his pit, coming in to repair a broken steering knuckle. In jumping out of the disabled car, Anderson, Jagersberger’s mechanician, slipped, fell and was run over by his own car. Harry Knight, leading a field of three cars fighting for the advantage at the turn, came thundering past the stands and saw the Case helper lying directly in his path. Knight threw on his brakes. His car turned halfway round and crashed into an Apperson that was standing at the pits. Knight and his mechanic were thrown from the machine and bruised, while the Apperson crew miraculously escaped injury. Knight either thought quickly and took a long chance with death to save Anderson’s life or lost his head in the crisis. That, like the amount of credit be- longing to Patschke for the Marmon triumph, still is a matter of dispute.

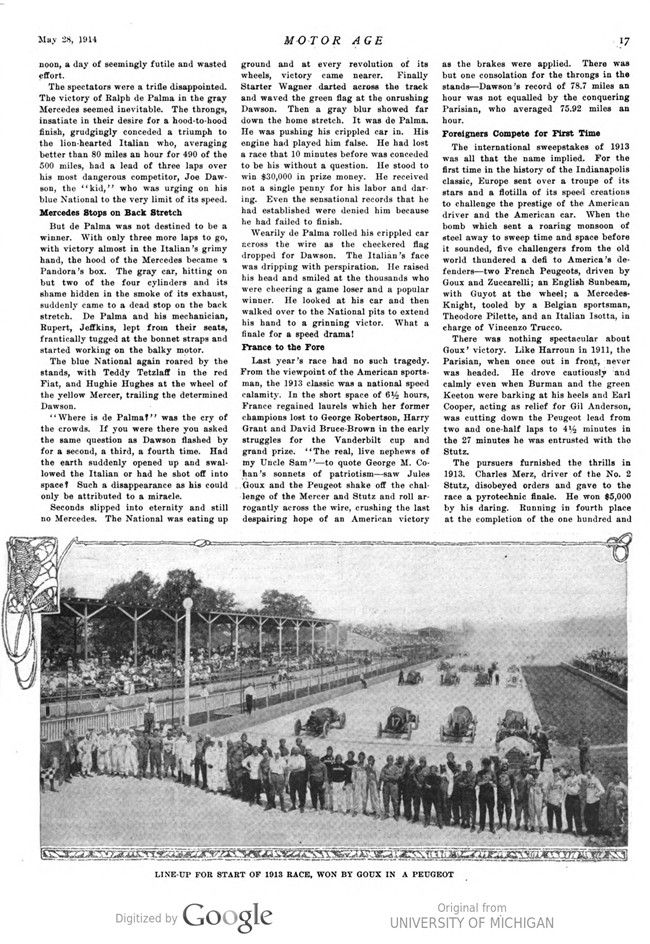

Dawson’s Victory Overshadowed

With the lapse of a year, came the second annual 500-mile race, the speed thrill perennial and a bloodless tragedy – a tragedy of defeat that overshadowed the victory of the persistent Dawson and his blue National that averaged 78.7 miles per hour in its journey of unexpected triumph. As the crushing of Napoleon eclipsed the history-making attack of Wellington at Waterloo, so the downfall of de Palma eclipsed the conquest of Dawson.

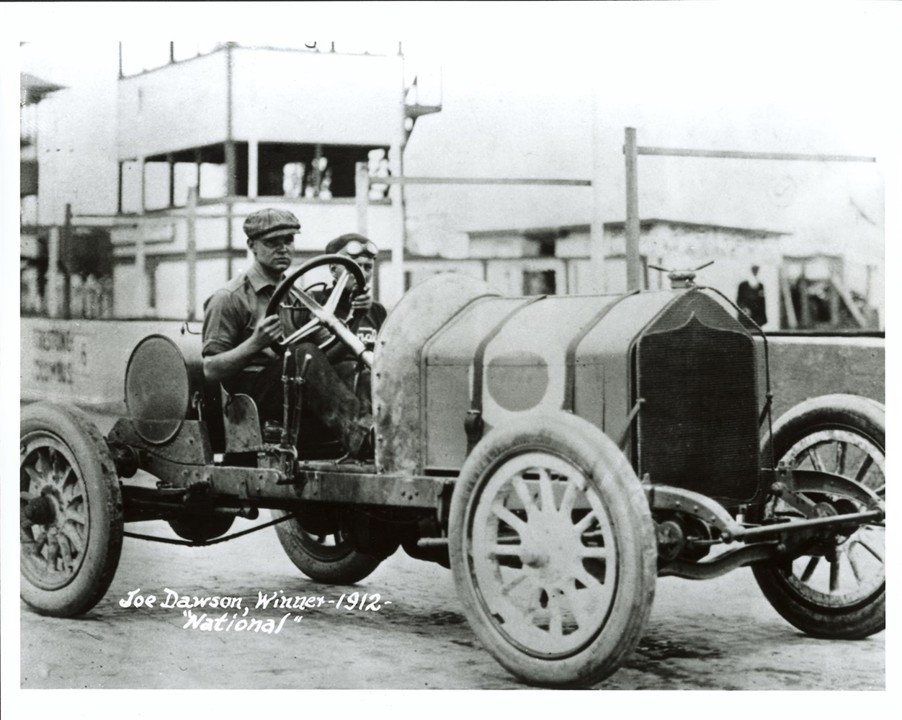

No race ever had a more spectacular climax than the international sweepstakes of 1912. At 10 o’clock in the morning, twenty-four cars, the speed creations of the master engineering minds of America and Europe, were sent away in the dense smoke of their popping exhausts. At the steering wheels of these steel monsters sat the greatest of all American racing drivers, mad Mullahs who defy the fates and court death to win fame and fortune, flying Mercuries of stout heart and taut nerves.

Of the four and twenty contenders that rumbled and roared a strident challenge at 10 o’clock in the morning, only ten were on the track at 4 o’clock in the afternoon It had been a day of minor disaster. Fourteen drivers had been forced to admit defeat before the climax of the day’s sport dawned. Of the fated fourteen, three had been tossed from their seats and bruised when their cars plunged from the track and somersaulted to destruction. The wrecks lay on the rim of the colossal oval, twisted, broken and foreboding. The others had docked disabled mechanisms at the white pits, cursing broken rods, weak bolts and faulty engines.

The Psychological Moment

One hundred and fifty thousand speed fanatics were awaiting the final thrill. The ten survivors were driving like men who had lost their senses. It was the psychological moment in a waning race that had been a heart-breaking chase since noon, a day of seemingly futile and wasted effort.

The spectators were a trifle disappointed. The victory of Ralph de Palma in the gray Mercedes seemed inevitable. The throngs, insatiate in their desire for a hood-to-hood finish, grudgingly conceded a triumph to the lion-hearted Italian who, averaging better than 80 miles an hour for 490 of the 500 miles, had a lead of three laps over his most dangerous competitor, Joe Dawson, the „kid,“ who was urging on his blue National to the very limit of its speed.

Mercedes Stops on Back Stretch

But de Palma was not destined to be a winner. With only three more laps to go, with victory almost in the Italian’s grimy hand, the hood of the Mercedes became a Pandora’s box. The gray car, hitting on but two of the four cylinders and its shame hidden in the smoke of its exhaust, suddenly came to a dead stop on the back stretch. De Palma and his mechanician, Rupert, Jeffkins, leapt from their seats, frantically tugged at the bonnet straps and started working on the balky motor.

The blue National again roared by the stands, with Teddy Tetzlaff in the red Fiat, and Hughie Hughes at the wheel of the yellow Mercer, trailing the determined Dawson.

„Where is de Palma?“ was the cry of the crowds. If you were there you asked the same question as Dawson flashed by for a second, a third, a fourth time. Had the earth suddenly opened up and swallowed the Italian or had he shot off into space? Such a disappearance as his could only be attributed to a miracle.

Seconds slipped into eternity and still no Mercedes. The National was eating up ground and at every revolution of its wheels, victory came nearer. Finally, Starter Wagner darted across the track and waved the green flag at the onrushing Dawson. Then a gray blur showed far down the home stretch. It was de Palma. He was pushing his crippled car in. His engine had played him false. He had lost a race that 10 minutes before was conceded to be his without a question. He stood to win $30,000 in prize money. He received not a single penny for his labor and daring. Even the sensational records that he had established were denied him because he had failed to finish.

Wearily de Palma rolled his crippled car across the wire as the checkered flag dropped for Dawson. The Italian’s face was dripping with perspiration. He raised his head and smiled at the thousands who were cheering a game loser and a popular winner. He looked at his car and then walked over to the National pits to extend his hand to a grinning victor. What a finale for a speed drama!

France to the Fore

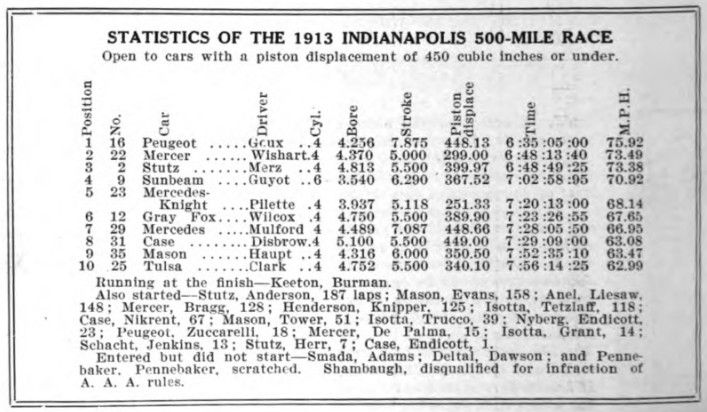

Last year’s race had no such tragedy. From the viewpoint of the American sportsman, the 1913 classic was a national speed calamity. In the short space of 6½ hours, France regained laurels which her former champions lost to George Robertson, Harry Grant and David Bruce-Brown in the early struggles for the Vanderbilt cup and grand prize. „The real, live nephews of my Uncle Sam‘ – to quote George M. Cohan’s sonnets of patriotism – saw Jules Goux and the Peugeot shake off the challenge of the Mercer and Stutz and roll arrogantly across the wire, crushing the last despairing hope of an American victory as the brakes were applied. There was but one consolation for the throngs in the stands-Dawson’s record of 78.7 miles an hour was not equaled by the conquering Parisian, who averaged 75.92 miles an hour.

Foreigners Compete for First Time

The international sweepstakes of 1913 was all that the name implied. For the first time in the history of the Indianapolis classic, Europe sent over a troupe of its stars and a flotilla of its speed creations to challenge the prestige of the American driver and the American car. When the bomb which sent a roaring monsoon of steel away to sweep time and space before it sounded, five challengers from the old world thundered a defi to America’s defenders-two French Peugeots, driven by Goux and Zuccarelli; an English Sunbeam, with Guyot at the wheel; a Mercedes-Knight, tooled by a Belgian sportsman, Theodore Pilette, and an Italian Isotta, in charge of Vincenzo Trucco.

There was nothing spectacular about Goux‘ victory. Like Harroun in 1911, the Parisian, when once out in front, never was headed. He drove cautiously and calmly even when Burman and the green Keeton were barking at his heels and Earl Cooper, acting as relief for Gil Anderson, was cutting down the Peugeot lead from two and one-half laps to 42 minutes in the 27 minutes he was entrusted with the Stutz.

The pursuers furnished the thrills in 1913. Charles Merz, driver of the No. 2 Stutz, disobeyed orders and gave to the race a pyrotechnic finale. He won $5,000 by his daring. Running in fourth place at the completion of the one hundred and eightieth lap, he moved up automatically to third position when his teammate, Anderson, was forced to retire because of a broken camshaft. For over 100 miles he had been driving desperately, refusing to give a second.

Gradually gaining inches when miles were needed to overtake Goux and Wishart, who was trailing the Peugeot in the Mercer, Merz was given the green flag after the latter’s car had started on its final lap. As he crossed the wire the front of his machine was aflame, and the Stutz pitmen waved him in. Merz saw the frantic signals but did not heed them. In a veritable chariot of fire, he drove the last 2½ miles with Martin, his mechanician, lying across the hood and beating at the flames with his bare hands. There is something to admire in men like Merz and Martin, men who never quit.

There were few spectators in the cheering stands who knew who Stevens was at the start of the 1913 race. He was an unknown, a faithful, never-quit boy who rode beside Ralph Mulford in the Mercedes. It was Stevens‘ first 500-mile race, but he was equal to the ordeal, more than equal as he proved near the close of the struggle.

Laying back at the start, Mulford gradually bettered his position as he reeled off lap after lap and at the end of 250 miles was in third place. He had not made a stop at the pits and his motor was sounding a menacing challenge. After running 275 miles without taking on fuel and breaking all records for nonstop competition, Mulford was the victim of that „‚unexpected something” that always happens in a motor car race.

With third place practically clinched and many predicting that he would pass the Peugeot eventually, Mulford ran out of gasoline on the back stretch. Leaping from the exhausted Mercedes, Stevens started for the pits, more than a mile away. Seconds are precious in a race for $50,000. Stevens may have been a tyro, but he knew that. Darting through the crowds in the infield, stumbling and falling in the high grass and weeds, jumping fences and creeks of sluggish water, he raced to the pits, staggering over the pit as not to be disqualified, cried, „Ralph’s out of gas, “ and fell in a faint. A fresh mechanic carried enough gasoline to Mulford to permit him to get to the pits to fill his tank and the old Mercedes continued the race, getting seventh place, where second might have been Mulford’s had it not been for his running out of fuel.

Such heroes as Merz, Martin and Stevens share the honors of the day with the victor of the 500-mile race, the world’s greatest speed spectacle.

IMS Indianapolis Motor Speedway

IMS Indianapolis Motor Speedway

IMS Indianapolis Motor Speedway