Text and pictures compiled by motorracinghistory with courtesy of hathitrust.org USA.

MOTOR AGE

VOL. XIV. No. 23 – CHICAGO, DECEMBER 3, 1908. – $3.00 PER YEAR

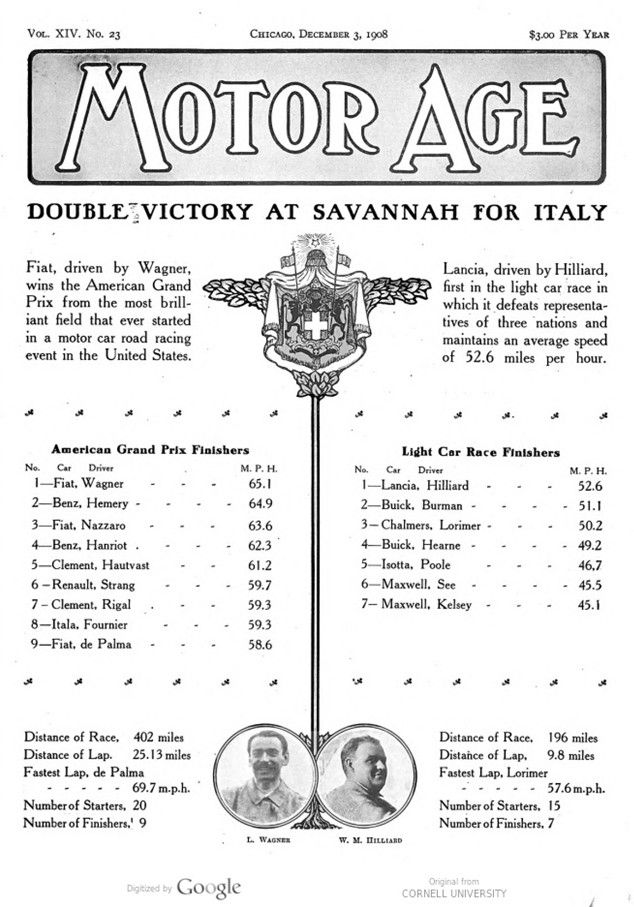

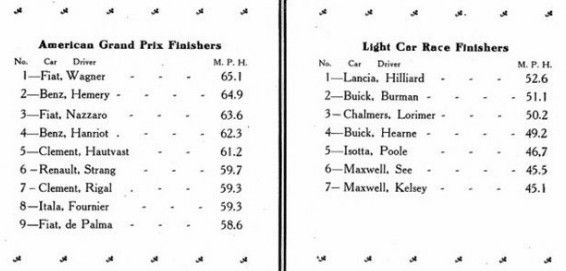

DOUBLE VICTORY AT SAVANNAH FOR ITALY

Fiat, driven by Wagner, wins the American Grand Prix from the most brilliant field that ever started in a motor car road racing event in the United States. Lancia, driven by Hilliard, first in the light car race in which it defeats representatives of three nations and maintains an average speed of 52.6 miles per hour.

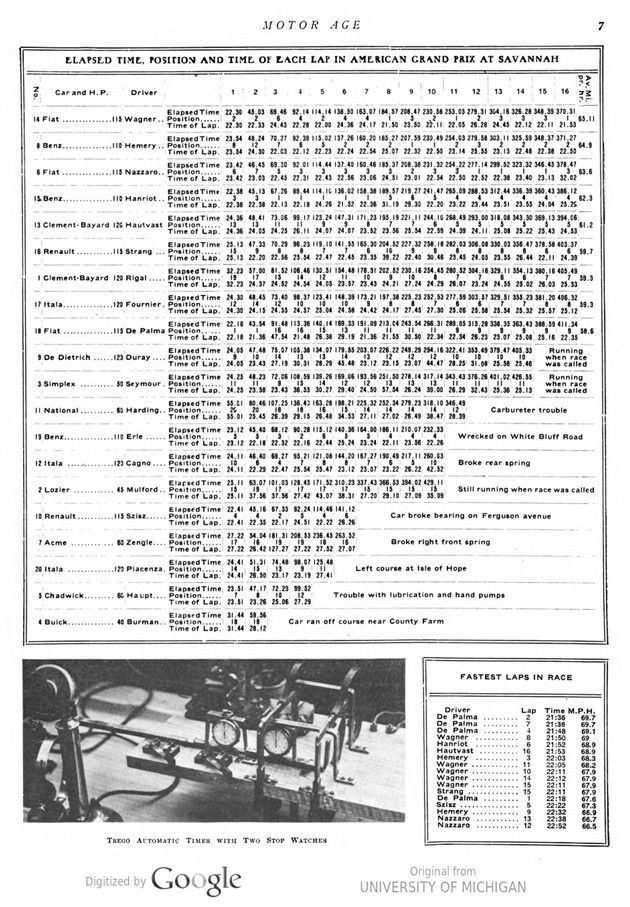

American Grand Prix – Distance of Race, 402 miles – Distance of Lap. 25.13 miles – Fastest Lap, de Palma 69.7 m.p.h. – Number of Starters, 20 – Number of Finishers, 9

Light Car Race – Distance of Race, 196 miles – Distance of Lap, 9.8 miles – Fastest Lap, Lorimer 57.6 m.p.h. – Number of Starters, 15 – Number of Finishers, 7

WAGNER IN FIAT WINS GRAND PRIZE FOR ITALY WITH HEMERY IN GERMAN BENZ CLOSE SECOND

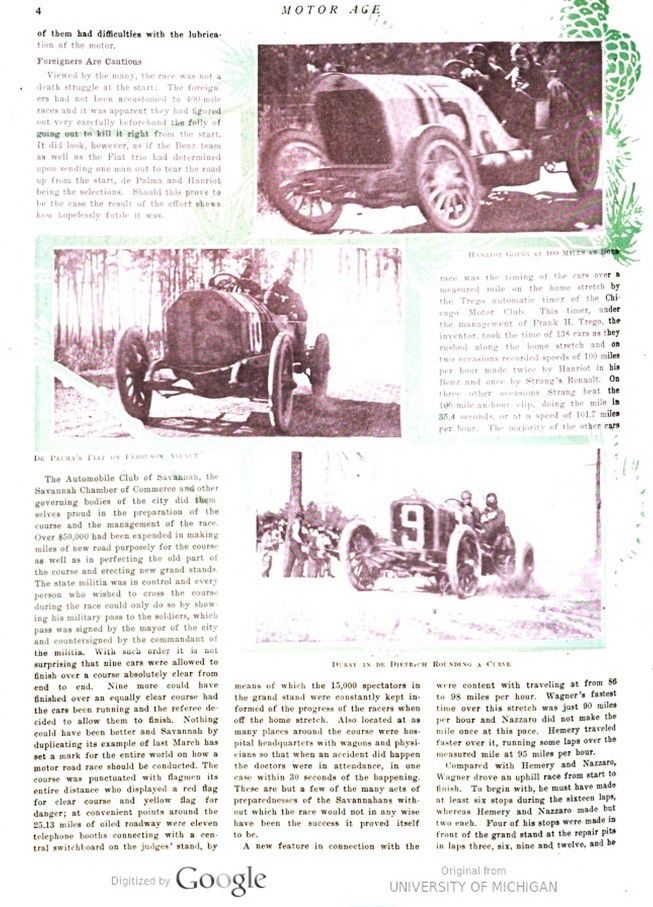

SAVANNAH, GA., Nov. 26—Italy today won America’s first grand prix race of 402 miles over a 25.13-mile circuit on the outskirts of this city, Louis Wagner, the hero of the 1906 Vanderbilt cup race, being the winning driver, piloting his Fiat racing car over the sixteen laps at an average pace of 65.1 miles per hour and beating his nearest rival, Victor Hemery, by the narrow margin of 56 seconds. Hemery, in his big Benz racing machine that triumphed over the Fiats in the French grand prix race this year, was a strong favorite and undoubtedly, he would have won the race by a few seconds had he not been wrongly instructed by his signal corps as to the proximity of Wagner. As it was, he averaged 64.9 miles per hour. Third honors also went to Italy, Felice Nazzaro carrying them off with another Fiat, which averaged 63.6 miles per hour for the circuit. Up till the last lap Nazzaro was the big favorite and was leading by a margin of 2 minutes, but a couple of tire changes crushed every hope of his admirers. Fourth honors went to another Benz car driven by Hanriot with an average pace of 62.3 miles per hour to his credit. Hautvast, driving a Clement car, annexed fifth position; Lewis Strang, the hero of last March’s races over the same course under A. A: A, auspices, was sixth in a Renault; Rigal, in a Clement, was seventh; Henri Fournier, in an Itala, eighth, and Ralph de Palma, in the third Fiat, ninth and last car to finish.

Only Nine Cars Finish

Only these nine cars finished the race before it was called off but three other cars were running, two American machines, Seymour in his Simplex and Mulford in a Lozier, together with the French driver Duray in his de Dietrich. Eight cars failed to finish the course, four of these being foreign machines and four American cars. Cagno in his Itala broke a rear spring in the tenth lap; Szisz broke a ball in a wheel bearing of his Renault in the seventh; Piacenza in his Itala ran off the course in the fifth and went out; Fritz Erle had an accident in the eleventh, wrecking his car on the White Bluff road; the Acme broke a front spring in the third and retired in the seventh; Burman’s Buick ran off the course in the third lap and retired; Haupt in the Chadwick had lubrication troubles and retired in the fifth, and the National driven by Harding had camshaft difficulties and withdrew in the twelfth. So ended the race, nine foreign cars finishing, no American machines completing the sixteen laps, twelve of the twenty cars that started running at the finish and six dropped before the end came.

It was not an American day in spite of the glorious sunshine of the south that brightened everything after the start of the race which was a duel from start to finish between the Italian Fiat cars and the Benz machines from Germany. There were three in each team and the machines were manned by the best drivers Europe can produce. These teams had met before this year on Europe’s roads where the Benz had won the day and the Fiat team was ready for the fray, determined to fight to the death to win back lost laurels. As results proved, the day went to the Roman descendants, who won first and third places, while Germany was given second and fourth. After the first few laps the Fiat team was practically reduced to a two-man affair by the troubles with oiling that de Palma encountered. As if to even matters up for the grand final act of the closing laps Fritz Erle in one of the Benz cars, dropped out in the tenth lap when he was running in fourth place.

American cars lost for two reasons – they were not ready for the race and were underpowered. National, Acme, Chadwick and Buick put in stock machines, Lozier had a new racing car that was fresh from the factory with not enough running to put it in shape and the Simplex had been altered before reaching Savannah simply by adding larger cylinders to the stock chassis. As the race proved, it is useless for medium-powered stock machines to compete with high-grade racing locomotives built by the foreigners and by the performance of which the status of the motor car industry in their countries is gauged. If America hopes to promote international races next year and expects the cream of the racing talent from across the water to compete it must build cars to meet the foreigner and not make a ridiculous showing by entering in a half-hearted, half-prepared condition and not finishing the course. The performance made by American cars in contrast with the work shown by the foreigners is not a true estimate of the standard of the American cars. The foreigners were ready to race a week beforehand; the Americans were not ready when Starter Wagner gave the signal at 9:45 this morning.

From a standpoint of speed the race was a disappointment to many of the Savannahans, who had played heavily on a 70-mile-an-hour clip. But there was no re son for placing such a high estimate, as only one or two laps at this clip were made in practice and in the race itself. The many turns killed fast traveling and as predicted in Motor Age a week ago the pace was slightly in advance of 65 miles an hour. The course was in the best condition it was possible to put it in with the exception of a little too much oil in places which to a degree had been rectified by strewing sand over the course the day before. The banked turns were a success, but there was not that fast traveling on them that the multitude had expected. None of the drivers with the exception of de Palma in his Fiat and Hanriot in his Benz, did phenomenally fast work, all of them preferring to drive mediumly fast and not be stopping every other lap to change tires. Felice Nazzaro, the speed king of Europe and who averaged 74.25 miles per hour over the Florio Cup race this year, did not take one of the turns fast, but shut off and coasted around them, with the result that he traveled over 375 miles without having to change a tire. On the other hand Hanriot and de Palma, who started out with space-devouring speed, had endless tire troubles and both of them had difficulties with the lubrication of the motor.

Foreigners Are Cautious

Viewed by the many, the race was not a death struggle at the start: The foreigners had not been accustomed to 400-mile races and it was apparent they had figured out very carefully beforehand the folly of going out to kill it right from the start. It did look, however, as if the Benz team as well as the Fiat trio had determined upon sending one man out to tear the road up from the start, de Palma and Hanriot being the selections. Should this prove to be the case the result of the effort shows how hopelessly futile it was.

The Automobile Club of Savannah, the Savannah Chamber of Commerce and other governing bodies of the city did themselves proud in the preparation of the course and the management of the race. Over $50,000 had been expended in making miles of new road purposely for the course as well as in perfecting the old part of the course and erecting new grandstands. The state militia was in control and every person who wished to cross the course during the race could only do so by showing his military pass to the soldiers, which pass was signed by the mayor of the city and countersigned by the commandant of the militia. With such order it is not surprising that nine cars were allowed to finish over a course absolutely clear from end to end. Nine could have finished over an equally clear course had the cars been running and the referee decided to allow them to finish. Nothing could have been better and Savannah by duplicating its example of last March has set a mark for the entire world on how a motor road race should be conducted. The course was punctuated with flagmen its entire distance who displayed a red flag for clear course and yellow flag for danger; at convenient points around the 25.13 miles of oiled roadway were eleven telephone booths connecting with a central switchboard on the judges‘ stand, by means of which the 15,000 spectators in the grand stand were constantly kept in. formed of the progress of the racers when off the home stretch. Also located at as many places around the course were hospital headquarters with wagons and physicians so that when an accident did happen the doctors were in attendance, in one case within 30 seconds of the happening. These are but a few of the many acts of preparedness of the Savannahans without which the race would not in any wise have been the success it proved itself to be.

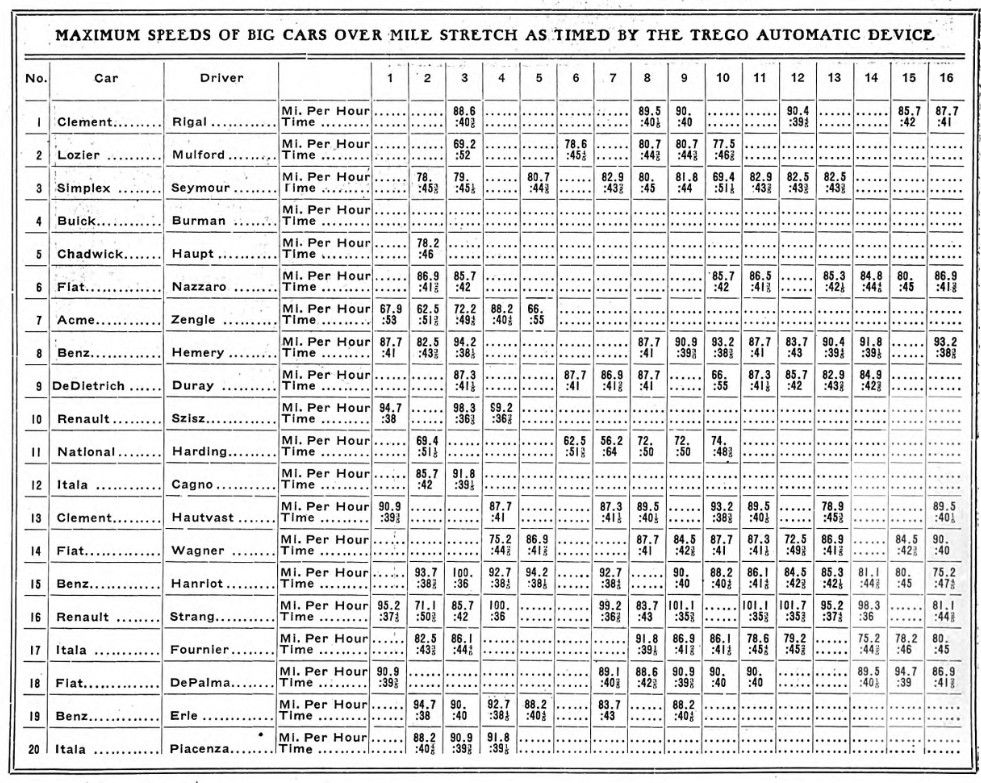

A new feature in connection with the race was the timing of the cars over a measured mile on the home stretch by the Trego automatic timer of the Chicago Motor Club. This timer, under the management of Frank H. Trego, the inventor, took the time of 138 cars as they rushed along the home stretch and on two occasions recorded speeds of 100 miles per hour made twice by Hanriot in his Benz and once by Strang’s Renault. On three other occasions Strang beat the 100-mile-an-hour clip, doing the mile in 35.4 seconds, or at a speed of 101.7 miles per hour. The majority of the other cars were content with traveling at from 86 to 98 miles per hour. Wagner’s fastest time over this stretch was just 90 miles per hour and Nazzaro did not make the mile once at this pace. Hemery traveled faster over it, running some laps over the measured mile at 95 miles per hour.

Compared with Hemery and Nazzaro, Wagner drove an uphill race from start to finish. To begin with, he must have made at least six stops during the sixteen laps, whereas Hemery and Nazzaro made but two each. Four of his stops were made in front of the grandstand at the repair pits in laps three, six, nine and twelve, and he changed two tires in other parts of the course. His first stop was at the end of lap three, when exactly 50 seconds were needed in throwing off the back of his car a worn tire that he must have taken off a wheel during the lap and in putting a new tire on the rack, which stop, together with that to make the change on the course, made his lap of 24.43 exactly 2 minutes slower than he had been running. In the sixth lap a similar stop was made, but 30 seconds only was used in getting the new tire and throwing away the old one. This lap, owing to changing the tire on the back stretch, was just 2 minutes slower than the pace of 22 minutes and some seconds that he was setting. Lap seven also was slow, the reason for which is not known. In lap nine gasoline and oil were taken on and an old tire thrown off, 1 minute 40 seconds being consumed. In lap twelve there was 2-minute stop for oil, changing the right front tire and doing some work on the jackshaft. This was the slowest lap of the lot, requiring 26:28. The last three laps were fast ones, in fact three of his four fastest laps: 22:12, 22:11 and 21:53. From these laps it is more than evident he was hitting a terrific pace, knowing full well that it was travel in this way or lose. All told, he lost 5 minutes in front of the grandstand as compared with 50 seconds lost by Nazzaro and 45 by Hemery. Eliminating all tire stops, it is apparent that from start to finish he drove at a pace ap- proximately 22 minutes 20 seconds to the lap, making an average of 67 miles per hour without stops.

It would scarcely be expected that a race of such consequence as the grand prix would pass off without a symptom of discontent. Scarcely had the spectators reached the hotels than rumors of a protest against Nazzaro were afloat. The manager of the Benz camp protested, claiming he received aid in changing two tires in the last lap on the White Bluff Road. Nazzaro admitted that the spectators aided in jacking up the car and in pushing it when he started, but also claimed that he tried to stop them, even going so far as to shove them away, but without success. After a hearing the protest was withdrawn. Scarcely had the last echoes of it died before a formal protest was lodged against Hanriot, who won fourth place. Hanriot ran out of gasoline just at the finishing line, having to coast over, but it also appears that he ran out at the upper end of the home stretch and borrowed some from a White steamer. This action would be sufficient to disqualify him, as the rules state that taking on gasoline or oil at other points than the grandstand pits would be penalized. The findings of the referee in the hearing have not yet been made known.

The facts regarding Hemery’s losing the race through a slip by his signal corp are briefly as follows: Hemery started 2 minutes after Nazzaro and never caught him until the last lap, but the two raced so closely together that the signals Hemery got each time he flashed past the grandstand were with regard to his standing with respect to Nazzaro. At the end of lap fifteen he got the signal 2-2-6, meaning he was in second place, 2 minutes behind car No. 6, which was Nazzaro, but nothing was said about Wagner, who started 6 minutes behind Hemery, and who was behind him on the course. As it was, Wagner finished lap fifteen only 2 seconds back of Hemery, but Hemery having passed the grandstand had no intelligence of it, and when in the last lap he overtook Nazzaro, he thought his big task was over and he had little to do but beat him out to the finishing line. In the mean- time, Wagner’s hot pace had overtaken Hemery. When Hemery passed the grandstand, he was greeted a winner and cheered to the echo, as he rushed by, ever slackening on the course to the scales. A little waiting followed, then the spectators realized Wagner had a big chance, which he took.

Michelin had the lion’s share of the tire equipment, having fifteen of the twenty cars fitted with his tires. Dunlop tires were fitted on the two Clement-Bayard’s, and the de Detrich, and Continentals on the Lozier and Simplex. The popular size for the rear wheels was 35.23 inches by 5.31, the Fiats, Benzes, Itala’s, Clements, de Dietrich, National, Simplex and Renaults using this size. The majority of these cars used 34.44 by 4.13-inch sizes on the front wheels. The Clements had very small front wheel tires, 34¼ by 3½ and it is interesting to note that not a change was made on the front wheels of these cars during the race.

The majority of the cars carrying Michelin tires used the new Michelin split rim, in which the ends of the rim are united by a turn buckle, which is tightened to fasten the rim and slackened to remove it. On the Clements and de Dietrich, the rear wheels were shod with the new Dunlop rim, which is the fastest on the market. The Continental rim was used on the Lozier and Simplex. Practically all of the cars began the race with studded treads, the heavy morning fog and too oily condition of the road making this necessary. In one or two cases a plain tread was used on the left front with good success.