In the last issue of 1920. la Vie automobile writes on the engine that won that years Indianapolis500.

Avec l’authorisation du Conservatoire numérique des Arts et Métiers (Cnum) – https://cnum.cnam.fr

Texte et photos compilé par motorracinghistory.com

La Vie Automobile Volume 16. — N° 720. – December 25, 1920.

The Indianapolis Winner

Doesn’t achieving an average speed in a car with a three-liter engine that is higher than that achieved by the 4 1/2, 6, 7, 8, and 9-liter engines in previous races clearly demonstrate the progress made in the construction of race cars? … It also shows what we can expect from the passenger cars of tomorrow.

The two men who designed and drove this modern machine to victory in an 800-kilometer race on a track as poor as Indianapolis, where thirty competitors in the most modern vehicles from the Old and New Worlds fought fiercely, can be justifiably proud of their triumph. This time, it was two brothers who achieved this feat: Louis and Gaston Chevrolet.

Louis Chevrolet is the man responsible for designing this magnificent car, and we are indebted to him for the permission he kindly granted us, as well as the documents he was willing to share with the readers of La Vie Automobile.

Gaston Chevrolet, the younger of the two, is a faithful student of his older brother (he could have had a worse teacher). We have noted the incomparable racing tactics of this skilled mechanic, whose name we already mentioned in our December 23 issue as the holder of the official 100- and 150-mile track records with average speeds of 177 km/h and 175 km/h.

I will not surprise most readers of La Vie Automobile by starting by pointing out what a “light car” is, the lightest car among the competitors, which here proves to be the most resistant, triumphing in the grueling test after five hours and forty minutes of fierce competition with an average speed of 142 kilometers per hour.

Looking back, we note that this little demon with a three-liter engine (except in 1915) broke all the previous Indianapolis Race records held by engines that were otherwise more powerful (at least in terms of displacement). In 1911, for example, when a 7-liter Marmon 300 came in first, with Fiat and Mercedes coming in second and third with 9-liter 800 and 9-liter 500 engines (130 X 190 and 130 X 180 engines), the winner’s speed was only 120 kilometers per hour.

— 1912, National and Fiat, first and second with 8 liters and 9,800 displacement, only averaged 126 kilometers.

— 1913, Peugeot 7 lit. 300 (108 X 200) gave us an average of 122. — In 1914, Delage won with a 6-liter 200 and an average speed of 132 km/h. — The year 1915 holds the record with Mercedes‘ 4-liter 500 and an average speed of 144 km/h. — In 1916 and 1919, Peugeot’s 4-liter 500 with 133 and 141 km/h averages.

For 1920, the small 3-liter Monroe gives us an average of 141 km/h.

In an issue of La Vie Automobile, commenting on these cars, he said that the cars were asymmetrical. On this subject, I received a letter from L. Chevrolet requesting a correction to this article, which is translated below:

“I do not know where La Vie Automobile got the information that our cars were off-center, because this is not the case. The engine, the chassis, and, in short, the entire assembly is centered.”

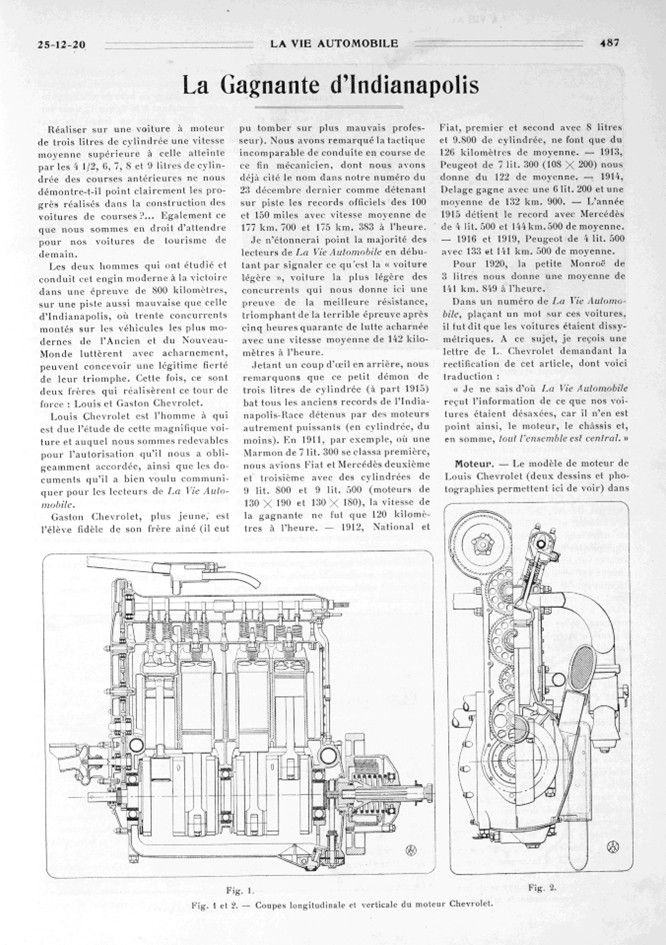

Engine. — Louis Chevrolet’s engine model (two drawings and photographs can be seen here) in all its details was mounted on two car models: Frontenac and Monroe.

The Frontenac car was considered the fastest car in Indianapolis, winning the first 95 prizes at the start, while the Monroe won the Grand Prix.

It is a four-cylinder engine with a bore of 79 mm and a stroke of 151 mm; it is not offset, the cylinders and crankcases form a single block of an ultra-rigid assembly, as can be seen in Figures 1 and 2. The explosions follow each other in the order 1-3-4-2. Each cylinder is fed by four valves with a diameter of 36 mm and a lift of 11 mm. Two overhead camshafts control the valves; to avoid lateral thrust from the cam on the valve stem, a small tappet and articulated lever are interposed. The camshafts are driven by the crankshaft via carefully mounted spur gears on ball bearings. The very rigid crankshaft is mounted on three ball bearings; the diameter of the connecting rod bearing is 54 mm. The connecting rods are tubular, the pistons are made of aluminum (lynite) and equipped with two rings; the piston pin is held fixed in the connecting rod and pivots in the piston bosses, thus providing a larger friction surface. The carburetor is a 50 mm Miller. For the first time, ignition was not entrusted to the magneto, and the “Delco” system used proved entirely satisfactory with a single “Mosier” spark plug located at the top center of the cylinder. The camshafts are lubricated under oil pressure, which is easy to do with plain bearings. The same cannot be said for a crankshaft mounted on ball bearings. The bearings will receive the necessary oil, but when it comes to the connecting rod bearing, things are more complicated with a crankshaft rotating at high speed: in this case, splashing will not do any good; the oil must therefore arrive through the center of the crankpin, from where it will be naturally projected by centrifugal force and will lubricate the connecting rod bearing as it passes. This principle has been masterfully implemented here by Chevrolet. The crankshaft has four rings with very large inner grooves attached to the crankshaft arm. Referring back to Figure 1, we can see a cross-section of this ring on the front arm of the crankshaft. The oil collected in this ring, by centrifugal force, is kept “under pressure, so to speak,” inside the circular groove, from where it can only escape through a hole in the crankpin corresponding to the connecting rod bearing, which it will lubricate as it passes. Water circulation is provided by a centrifugal pump. The clutch is of the multiple disc type. Three-speed transmission. Thrust and reaction by springs.

The length of the rear spring is 1 m 40. The rear wheels are controlled directly by a corner wheel without a differential. The wheelbase is 2 m 490 and the track is 1 m 420.

The tires used are 32 X 4 inches (813 X 101 mm) “Oldfield” tires at the front and 32 X 4 1/2 inches (813 X 114 mm) at the rear. The fuel tank holds 102 liters and the oil tank 30 liters. Total consumption for the 800-kilometer race was as follows:

Fuel 197 liters, Oil 22.7 liters, or per 100 kilometers: 24.6 liters of fuel and 2.8 liters of oil.

These figures are extremely high and clearly show that there is considerable room for improvement in terms of thermal efficiency.

A Lucand.

Photo captions.

Fig. 1 and 2. — Longitudinal and vertical sections of the Chevrolet engine.

Fig. 3. — The front of the Frontenac car.

Fig. 4. — The engine of the Frontenac car.