Text and jpegs by courtesy of hathitrust.org www.hathitrust.org, compiled by motorracinghistory.com

MOTOR AGE Vol. XXV, No. 23 Chicago, June 4, 1914

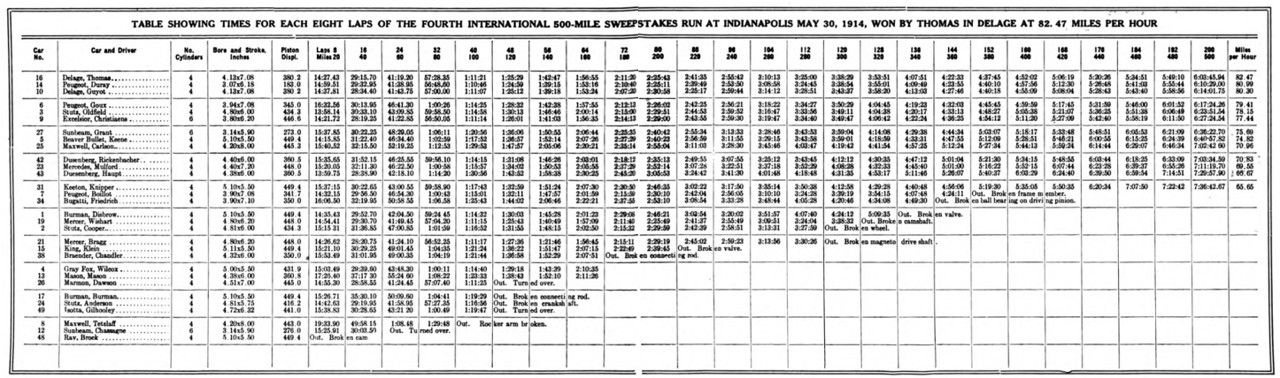

FRENCH DELAGE WINS 500 MILE RACE

By C. G. Sinsabaugh

INDIANAPOLIS, Ind., June 1 – Crossing the seas to fight out their feud of long standing which the road races of Europe have been unable to settle, the Delage triumphed over the Peugeot in the fourth annual international sweepstakes Saturday, run off on the Indianapolis motor speedway. At the same time Delage also won the American classic, humiliating a large field of American entrants, who had hoped that by the turn of Fortune’s wheel maybe one of their number might be lucky enough to pull down the big end of the $50,000 purse.

Vain hope! The foreigners not only won the race, but also captured second, third, fourth, and sixth while another foreign car—the Sunbeam, driven by an American, Grant–was seventh. Counting actual cash as pulled from the speedway purse of“ $50,000, the foreign drivers captured $40,700, leaving only a scant $9,300 to be divided among the five American pilots. Last year was a foreign landslide when the Europeans collected $26,500 with Goux’s first, Guyot’s fourth and Pilette’s fifth, but this year’s humiliation of the American speed kings was even greater.

Record for Race Broken

Added to this was still another humiliation — the 500-mile speedway record of 78.7 miles per hour was smashed not only by the winner but by the three other foreigners who followed him home, the top-notch figure being 82.47 miles per hour.

Rene Thomas was the bright particular star, the quiet, methodical driver, who had said he would average 83 miles per hour and who made good. When he got the checkered flag from Starter Tom Hay he was six laps ahead of his closest rival, Arthur Duray in the 183-inch Peugeot. Guyot, his Delage teammate, was running two laps back of Goux, while Goux, last year’s winner, was a lap back of Guyot. Oldfield, the only American within gunshot, was twelve laps back. So there was questioning the grand victory of Thomas.

Back of Oldfield came the stragglers, the drivers who were fighting for a piece of the money and who were not factors in the fight for first place — Christiaens in the Belgian Excelsior, Grant in the English Sunbeam, Keene in the Beaver Bullet, Carlson in the kerosene-burning Maxwell and Rickenbacher in the Duesenberg. Back of them were three others who were permitted to finish so as to prevent confusion in case of a disqualification of any of the first ten. This included Mulford in the Mercedes-Peugeot. Haupt in the Duensenberg and Knipper in the Keeton. Mulford was under the impression he was running to get the last money, just as he did 3 years ago, and consequently he was disgusted when he was told he finished eleventh.

In a way it differed from previous races in that it lacked the sensational features that thrilled the multitudes in other years. There was no last-lap battle as in 1911 when Harroun nosed out Mulford, nor did the leader blow up at the end as did de Palma in 1912, letting Dawson take the It was more like 1913, when Goux led the field and carried the lilies of France to their first international speedway victory. The lilies still are unsullied and unless the Americans take the racing situation more seriously, they will continue to wave from the flagpole when the next Indianapolis race passes into history in the summer of 1915.

There were more accidents this year than in previous events, one of which threatened to terminate fatally. In this Dawson, winner in 1912, was brought low and now lies in the hospital with the doctors hovering over him but holding out hope for his ultimate recovery. Dawson turned turtle trying to avoid the Italian Isotta which had upset in his path. Earlier in the fray Chassagne’s English Sunbeam had turned over, while Cooper’s Stutz lost a couple of wheels at a time when it was a factor in the battle.

Joe Dawson’s Accident

The Marmon-Isotta mix-up was the big sensation of the race. the race through the eleventh-hour withdrawal of de Palma’s Mercedes. He had been warned once by the officials for holding the extreme outside of the track while running at a comparatively slow pace, Gilhooley got into race. which made it hard for the faster cars to pass him. Evidently the warning went in no one ear and out of the other, for Gilhooley lapsed into his old habit soon after. He swung into the south turn, running high up, when a tire blew, capsizing the Italian car. Gilhooley’s dazed mechanic was crawling up the bank. Wilcox in the Gray Fox dodged him and Dawson started to cut through between the mechanic and the outside wall when he saw he could not make it without hitting the man.

To avoid this Dawson swung down the bank and tried to cut back again, but the Marmon turned over, flinging Dawson and his mechanic. Dawson was the most seri- ously hurt of the four involved in the wreck, but he had saved the life of poor Bonini.

Chassagne escaped from his accident with a few bruises, the worst being a cut under the eye, caused by the breaking of his goggles. This, however, did not incon- venience him any, but his car was out be- cause of the accident which was caused by the breaking of a wood wheel. Cooper’s Stutz, which was driven by his relief, Rader, at the time, broke two wood wheels following a tire blowout which ran the car off into the soft going on the inside.

Boillot Put Out

Boillot, the European champion, also was put out through an accident. In the lead and looking a possible winner, he threw a tire. Strangely enough the tire rebounded, striking Boillot on the arm, bruising it. Also it tore off the Frenchman’s necktie. The accident resulted in a broken frame which most effectually stopped the Peu- geot and left it up to Duray and Goux to uphold the reputation of the house.

Weather Ideal for Race

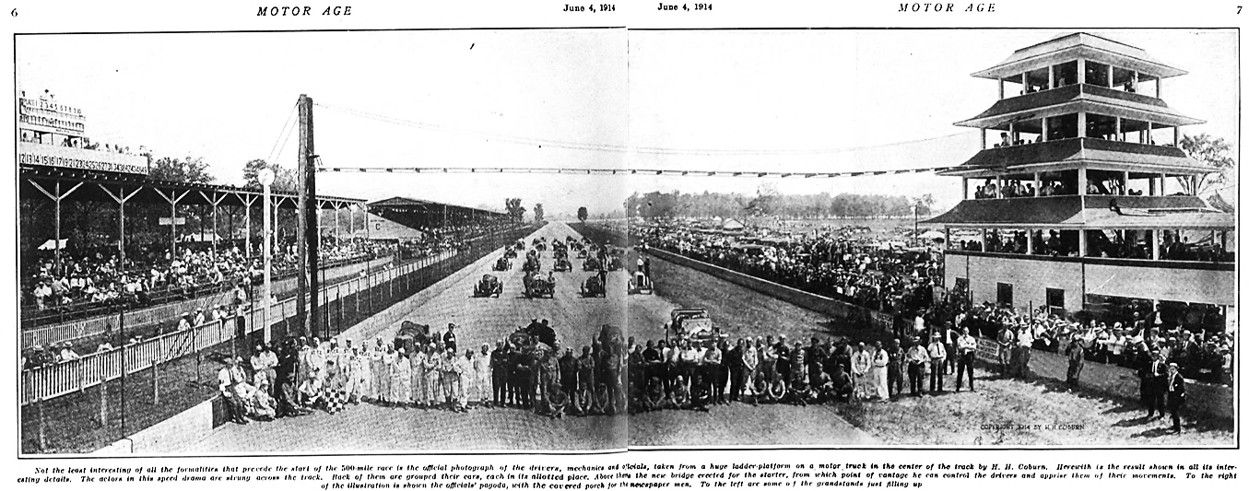

The morning of the great race brought a surprise to everyone. The night before it looked threatening and indeed it showered once. But Carl Fisher’s luck stood by him and the great day dawned most auspi- ciously. A cooling breeze was blowing, the sky was clear of clouds and as early as 7 o’clock a huge crowd was clamoring at the gates for admittance. This advance guard predicted a smashing of attendance record, which was verified before the day was over. Despite the fact that 10,000 additional seats had been provided, there were few empty spots in the huge stands by the time the race really was under way, and by noon it was said that last year’s figures had been exceeded by 20,000, the estimate of the attendance being placed at close to 125,000.

All preparations had been made for the efficient handling of the contest and there wasn’t a slip made in getting the field into motion. The usual brake tests were held and everyone qualified. Then came the grouping of the drivers, mechanics and officials for the big photograph. Then there was the parade of the drivers, each being followed by an introduction to the crowd after which the cars were located in position for the start itself.

The start differed from those of previous years in that the principle of safety first so far as the starter is concerned was adopted. There were none of the sensa- tional features of other races, with the starter dancing around in the smoke and dodging the cars. Instead, Tom Hay was safely located on a bridge that ran high over the track and from this vantage point he controlled the field most effectually and at the same time he was where every driver could see him.

The Start Interesting

The other preliminaries to the start were the same as before. There was the usual paced lap to get everyone in motion with Carl Fisher acting as pacemaker. With him rode Finley Porter, who held a watch in order to bring the real start as close to 10 o’clock as possible and make it easier for the timers and checkers by hav- ing the start on the even hour. It proved out, the big field getting under way on the real journey within a couple of seconds of 10 o’clock.

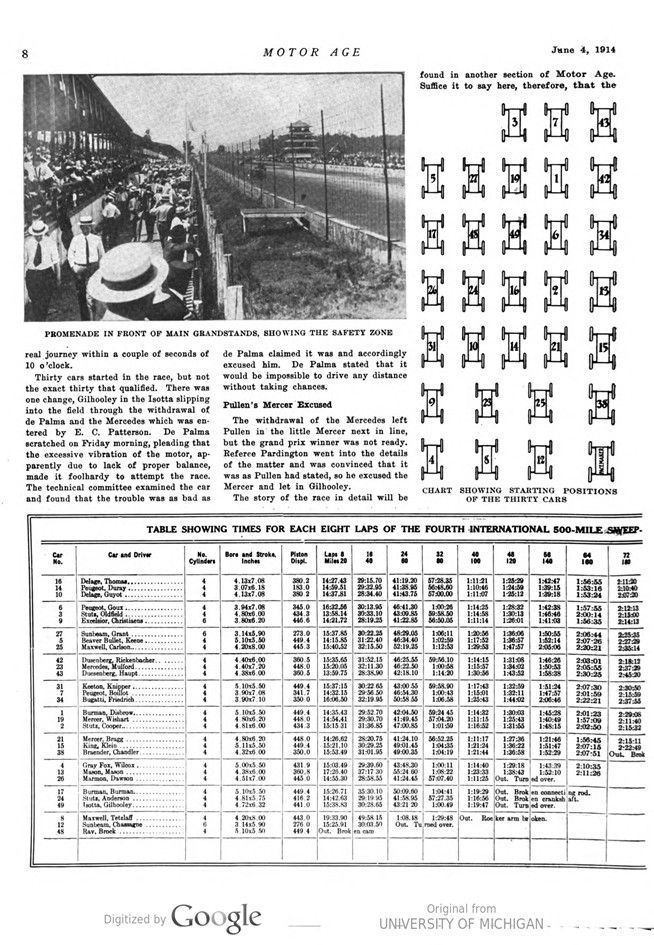

Thirty cars started in the race, but not the exact thirty that qualified. There was one change, Gilhooley in the Isotta slipping into the field through the withdrawal of de Palma and the Mercedes which was en- tered by E. C. Patterson. De Palma scratched on Friday morning, pleading that the excessive vibration of the motor, ap- parently due to lack of proper balance, made it foolhardy to attempt the race. The technical committee examined the car and found that the trouble was as bad as de Palma claimed it was and accordingly excused him. De Palma stated that it would be impossible to drive any distance without taking chances.

Pullen’s Mercer Excused

The withdrawal of the Mercedes left Pullen in the little Mercer next in line, but the grand prix winner was not ready. Referee Pardington went into the details of the matter and was convinced that it was as Pullen had stated, so he excused the Mercer and let in Gilhooley. The story of the race in detail will be found in another section of Motor Age. Suffice it to say here, therefore, that the battle for world honors was the keenest of the four that have been fought on the red bricks at the speedway. It was made par- ticularly interesting because of the intense rivalry that prevailed among the foreign- ers. It was as a house divided against it- self. Even among the Peugeotites there was rivalry, Goux and Boillot holding aloof from Duray because he was representing a private entry. There also was a coldness between Goux and Boillot and Guyot and Thomas that is known throughout Europe and America. The Peugeot and Delage long have fought for continental suprem- acy and the end is not yet. It will take the French grand prix next month to settle it.