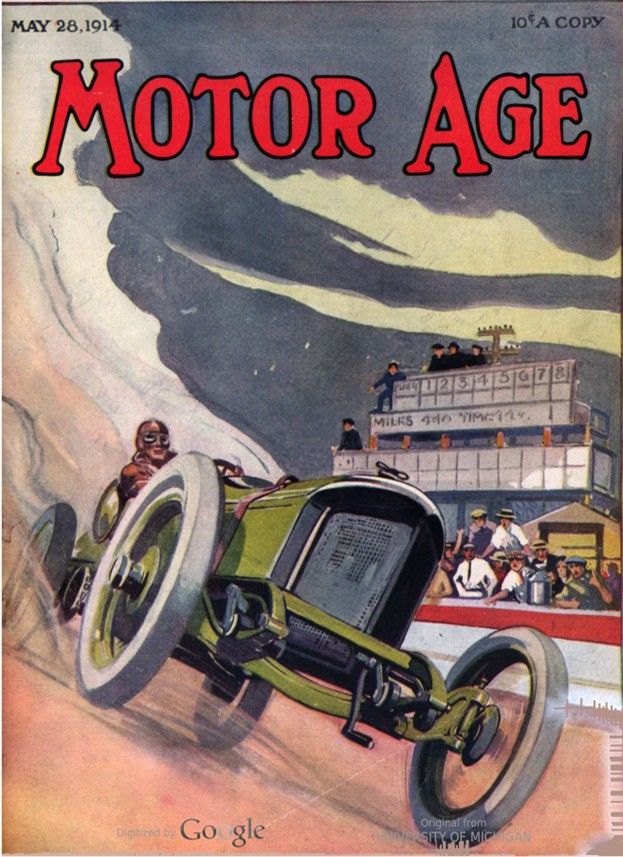

This impressive article on the person Carl Fisher was written in 1914 on the occasion of the fourth Indianapolis Sweepstakes. It describes not only the person, but it shows how he was driven in attaining his goal, based on his own earlier experience with cars and with motor racing. Once read, you’ll never forget!

Text and jpegs by courtesy of hathitrust.org www.hathitrust.org, compiled by motorracinghistory.com

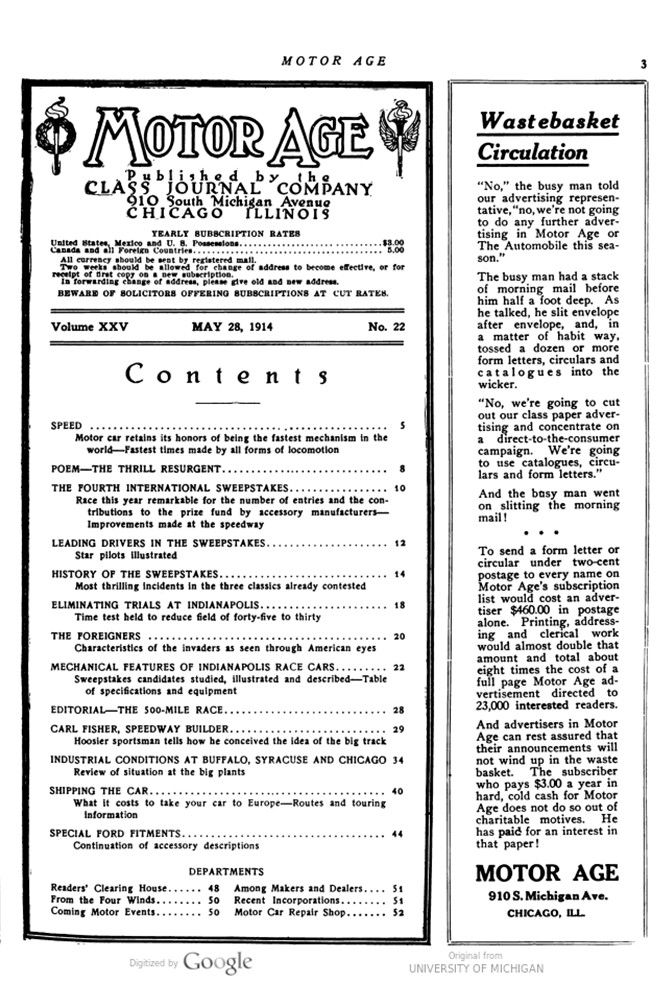

Motor Age Volume XXV, No. 22, May 28, 1914, pp. 29-41.

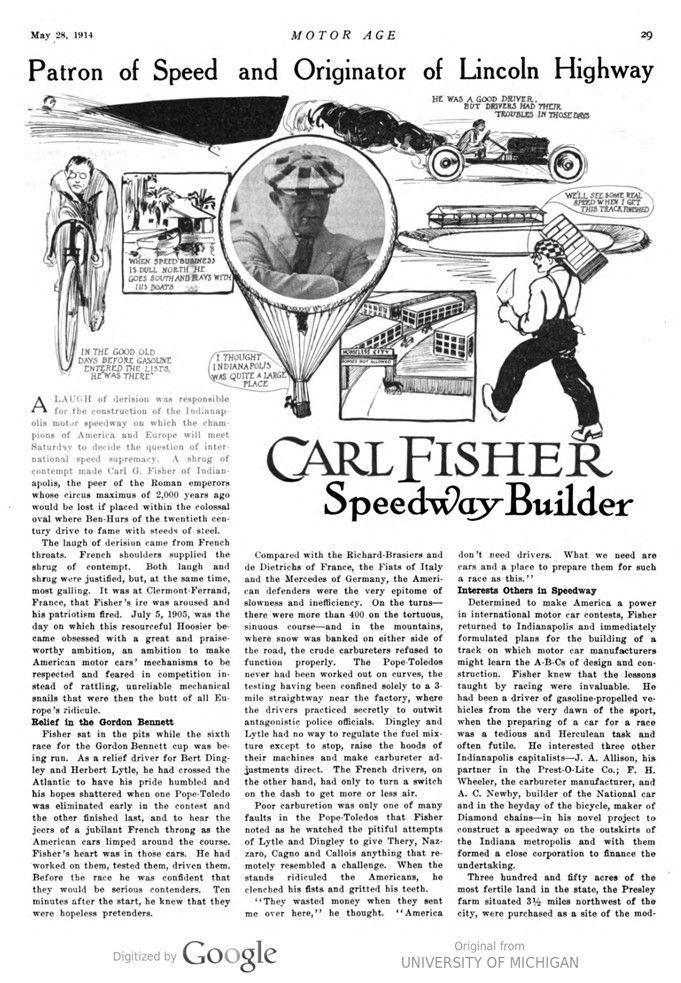

Patron of Speed and Originator of Lincoln Highway

CARL FISHER Speedway Builder

A LAUGH of derision was responsible for the construction of the Indianapolis motor speedway on which the champions of America and Europe will meet Saturday to decide the question of international speed supremacy. A shrug of contempt made Carl G. Fisher of Indianapolis, the peer of the Roman emperors whose circus maximus of 2,000 years ago would be lost if placed within the colossal oval where Ben-Hurs of the twentieth century drive to fame with steeds of steel.

The laugh of derision came from French throats. French shoulders supplied the shrug of contempt. Both laugh and shrug were justified, but, at the same time, most galling. It was at Clermont-Ferrand, France, that Fisher’s ire was aroused and his patriotism fired. July 5, 1905 was the day on which this resourceful Hoosier became obsessed with a great and praiseworthy ambition, an ambition to make American motor cars‘ mechanisms to be respected and feared in competition instead of rattling, unreliable mechanical snails that were then the butt of all Europe’s ridicule.

Relief in the Gordon Bennett

Fisher sat in the pits while the sixth race for the Gordon Bennett cup was being run. As a relief driver for Bert Dingley and Herbert Lytle, he had crossed the Atlantic to have his pride humbled and his hopes shattered when one Pope-Toledo was eliminated early in the contest and the other finished last, and to hear the jeers of a jubilant French throng as the American cars limped around the course. Fisher’s heart was in those cars. He had worked on them, tested them, driven them. Before the race he was confident that they would be serious contenders. Ten minutes after the start, he knew that they were hopeless pretenders.

Compared with the Richard-Brasiers and de Dietrichs of France, the Fiats of Italy and the Mercedes of Germany, the American defenders were the very epitome of slowness and inefficiency. On the turns – there were more than 400 on the tortuous, sinuous course – and in the mountains, where snow was banked on either side of the road, the crude carbureters refused to function properly. The Pope-Toledos never had been worked out on curves, the testing having been confined solely to a 3-mile straightway near the factory, where the drivers practiced secretly to outwit antagonistic police officials. Dingley and Lytle had no way to regulate the fuel mixture except to stop, raise the hoods of their machines and make carbureter adjustments direct. The French drivers, on the other hand, had only to turn a switch on the dash to get more or less air.

Poor carburetion was only one of many faults in the Pope-Toledos that Fisher noted as he watched the pitiful attempts of Lytle and Dingley to give Thery, Nazzaro, Cagno and Callois anything that remotely resembled a challenge. When the stands ridiculed the Americans, he clenched his fists and gritted his teeth. “They wasted money when they sent me over here,” he thought. “America don’t need drivers. What we need are cars and a place to prepare them for such a race as this.”

Interests Others in Speedway

Determined to make America a power in international motor car contests, Fisher returned to Indianapolis and immediately formulated plans for the building of a track on which motor car manufacturers might learn the A-B-C’s of design and construction. Fisher knew that the lessons taught by racing were invaluable. He had been a driver of gasoline-propelled vehicles from the very dawn of the sport, when the preparing of a car for a race was a tedious and Herculean task and often futile. He interested three other Indianapolis capitalists – J. A. Allison, his partner in the Prest-O-Lite Co.; F. H. Wheeler, the carbureter manufacturer, and A. C. Newby, builder of the National car and in the heyday of the bicycle, maker of Diamond chains – in his novel project to construct a speedway on the outskirts of the Indiana metropolis and with them formed a close corporation to finance the undertaking.

Three hundred and fifty acres of the most fertile land in the state, the Presley farm situated 3½ miles northwest of the city, were purchased as a site of the modern circus maximus, and early in the spring of 1909, work was started on the first and only speedway on the western hemisphere. Shovels in the hands of laborers became magic wands. Under the direct supervision of Fisher, the fields, where bumper crops of corn and wheat formerly had grown, were prepared for the reaping of world’s records. A 2½-mile track, with banked turns, was constructed of macadam. Monster grandstands, garages, a large aerodrome, aviation sheds and office buildings erected. Four miles of fence were necessary to inclose the plant. When the speedway was ready for its formal dedication in August, 1909, $460,000 had been expended.

The first meet held on the new track was a costly project. After 3 days of racing, which attracted 80,000 spectators to the speedway, the course was an oval of deep furrows. The macadam had failed to withstand the punishment inflicted upon it by fifty or more racing cars running over it at record-breaking speed. A new surface was imperative if another contest was to be held there and Fisher and his associates stoically assessed themselves $180,000 to defray the expense of reconstructing the track with vitrified brick and cement.

Polish Track with Cement Blocks

When the 3,500,000 bricks had been laid, it was discovered that the track was too rough to permit of high-speed work. Polishing was necessary to eliminate the outcroppings of cement, resulting from brushing, that cut tires to pieces after four circuits of the oval. After bids for this work were submitted by makers of electric polishers and scarifiers, Fisher decided that the expense was almost prohibitive. He therefore devised a plan for polishing the track that cost only $800. Hitching heavy cement blocks to a flotilla of test cars, he dragged them over the rough oval for 3 weeks. At the end of that time the track was as smooth as glass.

Another meet was held in the summer of 1910 and then Fisher conceived the idea of an international 500-mile race to be run annually. The contests of 1909 and 1910 had been over shorter distances and he wished to promote a contest that would put the cars to a more rigorous test. Ignoring the adage that warns us not to put all our eggs in one basket, Fisher proposed one race a year for the largest purse ever offered for a motor car contest and promptly put into execution such a plan, a plan that has met with popular favor, as the box office receipts for the past 3 years will show.

As the scene of only one race a year, the speedway is a most unique business proposition. The four stockholders in the corporation realize on their enormous investment but 1 day out of every 365. The annual receipts for 5 years have averaged $200,000, but the first dividend has yet to be declared. It is estimated that at the present time Fisher, Allison, Wheeler and Newby have $800,000 tied up in this project, a sum which includes the initial cost of construction and the expense of the many improvements that have been made within the last 4 years.

The motive that prompted the building of the speedway was the motive of the gentleman sportsman. Although an astute business man, Carl Fisher did not construct the speedway or promote the 500-mile race to realize directly on his investment. His main objects in each of these undertakings was to encourage the manufacture of more reliable motor cars, to teach lessons in races by which builders have profited in the design and construction of touring cars, to make the gasoline-propelled vehicle more dependable and concomitantly more popular. The speedway and the 500-mile race were only the means to an end much desired by him and profitable for him since the increased demand for motor cars has resulted in an increased demand for the accessories which he manufactures, lighting and starting systems. Fisher’s associates in the speedway have profited in the same indirect manner he – Allison, by the increased demand for Prest-O-Lite systems; Newby, through the disposal of more National cars; Wheeler, from a constantly growing market for carbureters.

That Fisher is sincere in his attempts to teach lessons by the promotion of the 500-mile race is evidenced by his attack on the use of castor oil as a lubricant and his reasons for that attack. His ultimatum against its use in the 1914 contest, rescinded last week, will stand next year.

„The use of castor oil teaches no lesson to the owner of a stock car because its cost is too prohibitive to permit of its general adoption,” he told the writer recently. “The average motorist will not pay $1 a quart for a lubricant. Next year we are going to reduce the piston displacement from 450 to 350 cubic inches. We already have shown the public that 450-inch motors are as fast and dependable as 600-inch motors and a similar lesson will be taught in next year’s race. We may increase the size of the purse. We want to get the foreigners over here. They can teach us a lot about building motor cars.“

Father of Many Projects

Carl Fisher is one of the most picturesque stars in the motoring firmament. As a promoter of things worthwhile, he holds the world’s championship. In his brain have been born several ideas that have developed into wonderful projects through his tireless energy and masterly direction. He is the father of the speedway, the 500-mile race, the Lincoln highway and the horseless city. Had he lived in the age of fairies, he would have worn the seven-league boots. Speedy locomotion is his hobby. He has experimented with every device that has been made to carry man over the most ground or water in the least time.

In his youth, the speedway builder concentrated his athletic activities on skating. He raced on both ice and roller skates. He designed and manufactured the skates which he used in contests and by the publicity and prestige gained through victories, he boosted the sale of his products. With the coming of the bicycle, he switched his allegiance from skates to the two-wheeled vehicle. Again he made sport and business affinities, riding in races the make of bicycle for which he acted as agent.

„I never was a champion,“ he declared, “although I’ve taken the dust of the best of them – Eddie Bald, Earl Cooper, Fred Titus and Arthur Zimmerman. I was only a second-rater, but I made money at the game and designed, manufactured and sold the wheel that I rode.“

Imported DeDion Motor Tricycle

Fisher became an enthusiastic convert of the gasoline-driven vehicle in 1898, when he purchased at a cost of $650 the second motor tricycle that the DeDion factory imported into this country. It had a 2½ horsepower engine and wire wheels. The gears were open and exposed and at the conclusion of each race, Fisher had a polka-dot makeup. Lubrication was made en route by the acrobat-driver who carried a small can of grease and a paddle, with which to oil the gears, as part of his racing equipment.

Fisher’s brother also bought a motorcycle and the two traveled during the summer throughout the west and south, giving exhibition races at county fairs. At a contest held at Osgood, Ind., the crowds swarmed out on the course and almost stopped the race. In an attempt to clear a way through the astounded spectators, Fisher ran into two empty coal oil barrels, wrecking his machine and upsetting two pairs of rural lovers who had sought a place of vantage on top of the barrels.

After the accident, the victims invited Fisher and his brother to take dinner with them. Although one of the girls suffered a broken arm and the others appeared swathed in bandages, they did not sue for damages but thanked their guest for running over them. In those days bruises and fractures sustained in a collision with a motor-driven vehicle were regarded as marks of distinction and caused much envy among those less fortunate or unfortunate, whichever way you look at it.

In 1901, Fisher made his debut as a motor car speed king at a county fair at Dallas, Tex. He was matched to meet sixteen running horses in a 1-mile race, two bang-tails to run an eighth of a mile each. Fisher’s machine was the first racing car that Alexander Winton turned out. It was lighter than the stock model and had a 1-inch longer stroke and ½-inch bigger bore. Its best time was a mile in 1 minute 43 seconds and as a freak, it was a greater attraction than the bearded woman or the two-headed calf.

The morning of the race, Fisher found that there was no gasoline to be had in Dallas and he was forced to accept as a substitute the worst kind of coal oil adulterated with paraffine. It took him 30 minutes to get his car ready to start, as he had to heat the head of the cylinder with a blow torch to vaporize the heavy fuel. That first race at Dallas can best be described as a chaos. The initial pop of the exhaust was a signal for a general stampede. The horses on the track bucked and snorted with fright. The horses inside the track ran wild, overturning wagons and scattering men and women all over the grounds. There was some talk of a lynching bee as Fisher was beating it for the state line.

But Carl Fisher is anything if not persistent. He continued to pit his Winton against race horses in exhibition events held at fairs conducted by the Benevolent and Protective Order of Elks at that time. His summer campaign of 1901 was a tremendous financial success. He charged from $600 to $1,500 for each exhibition. After driving in the race, he took modern adventurers around the track at $10 per mile and often cleaned up as much as $250 in one afternoon. Although his rates were exceedingly high, he never ran foul of the interstate commerce commission. When the first snow of winter fell and Fisher put the exhausted Winton into winter quarters, he checked up with his banker and found that he had cleared $20,000 as a county fair freak and barnstormer.

Motor Car Agent in 1900

After another summer of exhibition races equally as profitable, he took the Indiana state agency for the Oldsmobile and Winton. He was no tyro at selling cars. He had been agent for the Mobile steam wagon in 1900 and was regarded as a pioneer when it came to selling horse-less carriages. He discarded his one-lung Winton for eight-cylinder Premier, the first car in America to have a magneto and the second eight-cylinder machine to be built in this country. He formed alliance with Walter Winchester, tamer of an antique Franklin; Earl Kiser, master of the Winton Bullet; Barney Oldfield and Tom Cooper, who were experimenting with two of Henry Ford’s creations; and Louis Chevrolet, one of the first of the foreigners to drive in this country, and promoted dirt track meets and drove in races all over the United States. He went through the fence twice, but escaped serious injury. After participating in a contest, he would circulate among the crowd in search of gullible prospects.

“I’d give them a thrill and then operate on their bank rolls,“ he said. „The sport was new and the interest in motor car racing was keen. I couldn’t lose. Fifteen thousand a big crowd in those days. Times have changed. It takes 15,000 lemonade peddlers, peanut venders, program pirates and newspaper men to run a race meet today. What’s worse, they all get in free. The 15,000 of 11 years ago paid at the gate.”

Fisher drove his last race in 1905. With the money he made as a bicycle and motor car agent and his rake-off from dirt track campaigns, he got control of an illuminating system and started the Prest-O-Lite Co. Incidentally, he laid a foundation for a fortune that today is estimated at $4,000,000.

Becomes Convert to Balloon

But Carl Fisher had to have a substitute for the racing car which he had spurned. He became an enthusiast over ballooning and took to the air where there were no fences to crash into. In his monster gas bag, Indiana, he started from Indianapolis in the international balloon races of 1909 and sailed for 47 hours before he alighted in Georgia. He didn’t have to come to earth. He just wanted to. He hadn’t smoked for 2 days. He burnt up two cigars, soared aloft once more, landed in Tennessee and established a world’s endurance record.‘ The record was not allowed, however. The two cigars cost him the title of international champion. But he says that the price he paid for the smoke was ridiculously cheap. No doubt it was. As a suitor of Lady Nicotine, Carl Fisher is in a class with General Grant. One reason he hates to die is because he’ll leave “so many good cigars behind for a lot of boobs that don’t appreciate them.“

The speedway builder also can qualify as a near aviator. Two years ago he built a biplane and attempted a number of flights in it. He succeeded in hurdling several fences that obstructed his right-of-way, but never got far enough off the ground to dispute any of the altitude records held by Beachey and the Wrights. The machine is now accumulating a covering of dust and rust in the huge aerodrome at the speedway.

As a driver of motorboats, Fisher has gained national fame. Two or three years ago he was a victorious contender in several of the western regattas with the Eff with which he won the feature event of the Cadillaqua celebration at Detroit in 1912. He recently disposed of the Eff and the other craft in his flotilla, but he has two speed boats and one hydroplane building for use at his summer residence near Miami, Fla.

Just to prove his athletic versatility, Fisher goes in for deep sea fishing and talks nonchalantly of spearing a ton of tarpon, red snapper and muskellunge in the short space of an afternoon. Among the semi-savage negroes of the islands off the coast of Florida he is king of the barbeque. He cruises to their haunts, eats the wild hogs that the natives slay and cook for him and his guests, dances through the night in century-old houses to weird and barbaric music.

The motor car is Carl Fisher’s fetish. He always has had unbounded faith in its possibilities. When he stuttered around the dirt tracks in his one-lung Winton, he saw in the dust a vision of the modern touring car, a mechanism of stamina, power and refinement. It was such faith that brought about the conception and promotion of the Lincoln highway, a patriotic project that will be associated with the name of Carl Fisher long after the speedway stands rot away and the bricks of the red oval are no more. A decade ago he prophesied that the motor car would be a vehicle of transcontinental travel with the improvement of the country’s highways, and 2 years ago organized the association that is linking New York to San Francisco with a concrete boulevard. With Carl Fisher behind the project, the Lincoln highway has been changed from a dream to a reality. Millions of dollars have been subscribed for its construction, the route has been logged and marked and hundreds of miles of road have been improved within the past 2 years.

“It never will be finished,” Fisher declares. „Future generations always will be working on it. The completion of one improvement will only mark the beginning of another. It is a labor for all time.“

„No Horses Admitted‘

Speedway, the horseless city, is another of Fisher’s projects which sprang into being because its progenitor believed in the future of the motor car. In his brain he conceived a settlement near Indianapolis where the motor car and accessory manufacturing activities could be centered and where horses would be barred. It was a feasible idea. He started to build such a city. He backed it with his capital and his energy. It is a reality today.

Carl Fisher is a bon vivant of the right sort. He has found life very, very good. He is a connoisseur of foods and tobacco. At smoking a cigar, he is an artiste. He seems to relish each puff. He loves to travel at high-speed. He drives his cars on the country around Indianapolis as if he were out after records. His foot is always on the throttle.

The speedway builder sincerely believes that he owes the world much in return for what it has given him. For that reason he is a booster – a booster for his city, his state and his country.

Fastidious in dress, a trifle eccentric, exceedingly foresighted and a player of the game for the love of the game, Carl G. Fisher has done much for motoring in America. The speedway is a monument to his energy; the 500-mile race a tribute to his patriotism. He is a resourceful man who sees far into the future through the tortoise-rimmed glasses that he wears and the future of the motor car will be all the better because of his seeing.