Again, Charles Faroux has written reports in La Vie Automobile, on the 1921 French Grand Prix at la Sarthe road course. This last one is something like an after-the-race analysis, in which a graphical representation shows the time difference between several drivers during each race lap. Translated by deepL.com.

Text and jpegs with courtesy of the Conservatoire numérique des Arts et Métiers (Cnum) http://cnum.cnam.fr

compiled by motorracinghistory.com and translated by DeepL.com

— LA VIE AUTOMOBILE — Vol. 17. N° 734. August 10 1921

AFTER THE GRAND PRIX

For the first time, an American car has won a road race organized on the Old Continent. Such is the striking result of July 25. It shows the immense progress made by American manufacturers since the days when they sent cars to our motor races whose bizarre design earned them such legitimate success as curiosities.

This should not come as too much of a surprise, as we are carrying the burden of four and a half years of war. While we had other concerns than automotive technology, the best pre-war European race cars were acquired by Americans, crossed the ocean, and served as subjects of study and experimentation for our colleagues across the pond. So our pride can find some consolation for our defeat in the fact that we were beaten by a car built in America, but which incorporates French solutions and is descended from the winners of our Grand Prix and our Light Car Cups.

From a purely technical point of view, we can only rejoice at the result of the Grand Prix, which confirms the theories we have always supported. Victory went to the fastest engine, the one with the longest stroke and therefore the highest piston speed. It also went to the lightest car, the one with the strongest acceleration. Finally, we know the role played by brakes in this event, and that they contributed to the success perhaps as much as the engine. However, the Duesenbergs had French brakes; their powerful hydraulic brakes are simply a reproduction of a device patented by Rolland-Pilain, which was coldly plundered by an American group from which Duesenberg acquired the license for a fee. This should further soften the bitterness of our failure.

Another lesson learned from the race is the enormous progress made in tires. The speeds of 175 and 180 kilometers per hour reached by the competitors were once speeds that tires could not withstand. We remember that in many competitions, the fastest cars were victims of their own speed, which the tires of the time could not withstand: such as the Clément-Bayard cars in Dieppe in 1908, which reached precisely 175 km/h. However, nothing of the sort happened at Le Mans: the tires, especially the Pirelli tires, performed admirably, allowing us to record the highest average speed ever seen in a Grand Prix.

But the most striking fact of the day is undoubtedly Goux’s remarkable race in the little 2-liter Ballot. Seeing this little car finish third, with an average speed of over 115, and beat most of the 3-liter cars, except for one, the formidable Duesenbergs, is a magnificent revenge for Ballot. This also clearly shows that the 3-liter formula is too broad.

The question therefore arises as to what the regulations for next year’s Grand Prix will be, as I do not want to assume for a moment that it will not take place, which would be a serious mistake that we will not make. If the regulations on engine capacity are retained, the 2-liter formula seems ideal.

Finally, the sports commission must make its decisions quickly and announce them early, so that our manufacturers can get to work. Above all, it is essential that they come to the Grand Prix in large numbers and do not leave the brave Ballot alone to bear the heavy burden of upholding the reputation of French manufacturing. The future and prosperity of our automotive industry depend on it.

C. Faroux.

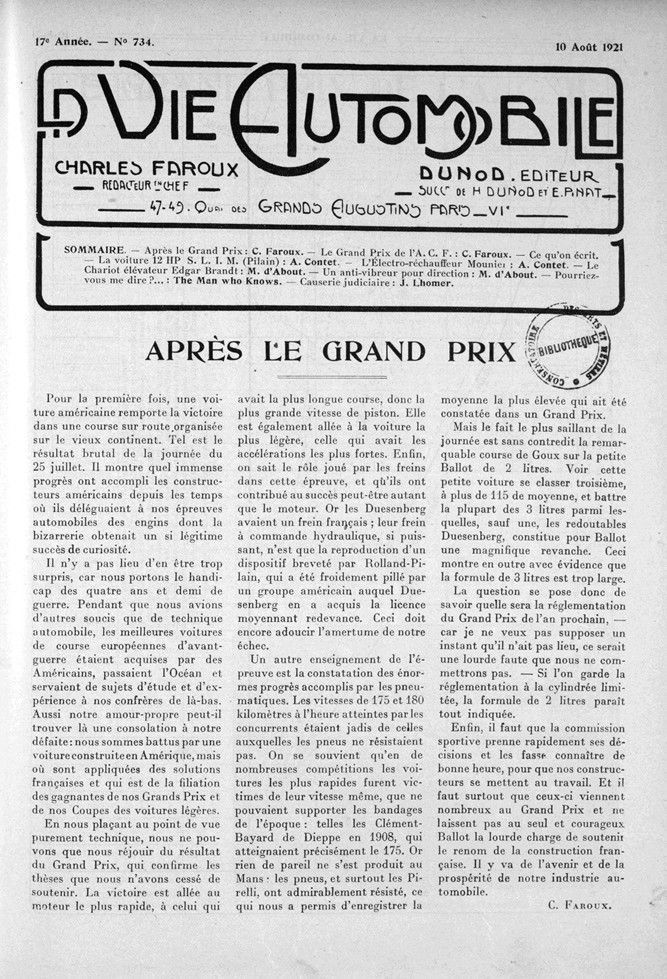

Page 274. – Performance graph for some Grand Prix competitors.

This graph was created as follows: the OX line represents the performance of a car that would complete all laps uniformly in 9 minutes. For each competitor on each lap, the differences between their time and that of this car were plotted above OX if they were negative, and below if they were positive. Thus, Murphy, having completed 4 laps in 31′ 46“ instead of 36 minutes, was plotted above OX with a difference of 4’14”.

The slope of the curve thus obtained is proportional to speed, showing that Murphy slowed down from the twentieth lap onwards, and even more so towards the end. Note the consistency of Chassagne and De Palma.

THE A.C.F. GRAND PRIX.

The A.C.F. Grand Prix took place on July 25 at the Le Mans circuit, under the conditions we have already described. Remember that competitors had to complete thirty laps of the circuit, which measures 17km,262, for a total distance of 517 km,860. The rankings were as follows:

1. JIM MURPHY in a DUESENBERG, covering the 517 km, 860 m course in 4 hours, 7 minutes, 11.2 seconds, or 25 km, 702 m per hour.

2. Ralph de Palma (Ballot) 4 hours, 22 minutes, 8.1 seconds

3. Goux (Ballot) 4 hours, 28 minutes, 38.1 seconds

4. A. Dubonnet (Duesenberg) 4 hours, 30 minutes, 19.1 seconds

5. A. Boillot (Talbot-Darracq) 4 hours, 35 minutes, 47 seconds

6. A. Guyot (Duesenberg) 4 hrs 43 mins 13 secs

7. Wagner (Ballot) 4 hrs 48 mins 1 sec

8. Lee Guiness (Talbot) 5 hrs 6 mins 43 secs

9. Seegraves (Talbot) 5 hrs 8 mins 6 secs

Not placed: Thomas (Talbot-Darracq), stopped on his 23rd lap (when the circuit was reopened to traffic); Boyer (Duesenberg), on the 18th lap; Chassagne (Ballot), on the 17th lap; and Mathis (Mathis), on the 6th lap.

The race. —- As was easy to predict, it was a duel between Duesenberg and Ballot. From the start, Boyer, in a Duesenberg, took the lead, which he soon ceded to his teammate Murphy. Murphy remained in the lead until the 11th lap, when, while stopping for 2 min. 15 seconds to change two wheels, Chassagne, in his Ballot, took the lead. We began to hope that victory would finally reward Ballot’s efforts when, on the 17th lap, Chassagne had to retire, his fuel tank having been punctured by a stone.

Murphy then took the lead again and, no longer feeling threatened, finished the race by taking care of his car, ahead of de Palma and Goux.

The winner. — For the first time, an American car won a major road race in our country, a perfectly fair and justified victory. It went to the fastest engine, with the longest stroke and therefore the highest linear piston speed. These engines run at 4,000 rpm, giving a piston speed of 15.7 m.

Two other factors favored the Duesenbergs. First, their light weight: they were 150 kg lighter than the Ballots, which is a significant advantage on a small circuit like Le Mans, where there are frequent accelerations. Secondly, the power of their hydraulically controlled brakes. All this resulted in a gain of a few seconds at each turn, which added up to a significant total over the entire circuit.

The average speed of 125 km/h achieved by the winner was the highest ever recorded since the Grand Prix began. The fact that it was achieved with a small 3-liter engine on a circuit such as Le Mans speaks volumes about the progress that has been made. Until now, the highest average speed had been set by the late Georges Boillot on the Amiens circuit in 1913, with 116.190 km/h. The car he was driving had a 100×180 engine, with a displacement of 5.6 liters.

With Duesenberg, Delco ignition triumphed, proving itself to be the real solution for high-speed multi-cylinder engines, i.e., whenever the ignition system has to deliver sparks in rapid succession. The Rudge wheel also played its part in the victory, but this was a foregone conclusion, as all the competitors had adopted it, except Mathis, who was not in contention for first place. The same was true of the Hartford shock absorber, which was fitted to all the cars that started the race.

Let’s make one more observation: the Duesenbergs have left-hand drive. This is the first time that a left-hand drive car has competed in a major road race in France and won.

The unlucky ones. — First and foremost, we must mention Ballot, who has been dogged by bad luck for two years without losing his tenacity. His cars, perfectly designed and impeccably built, were big favorites; their four-speed gearbox seemed to give them an advantage at the start, and their engine was built with Ballot’s renowned expertise. Consider that the average pressure was an extraordinary 10 kilograms per square centimeter, and that the engine torque per liter of displacement reached 7.5 meter-kilograms!

Two of the Ballot team’s men, in particular, carried our hopes: Wagner and Chassagne. The former had some early problems that he was able to fix, but which caused him to lose all hope of winning the race; the latter was stopped on the 17th lap by a stupid accident: his fuel tank punctured. That left de Palma, as Goux could not claim first place with his car, which had a displacement of only 2 liters. But de Palma’s car did not have the power brakes that Chassagne had, so he lost time at every slowdown due to slower braking and was unable to challenge Murphy. Had he had brakes as powerful as Chassagne’s, he could have taken over from him, forcing the Duesenberg to work at full capacity, and the outcome of the race could have been very different.

But Ballot can take consolation in the admirable performance of Goux in his small 2-liter car. This car, equipped with a 69.9 x 130 four-cylinder engine, ran without any failures or incidents, had only one stop due to a flat tire, and took third place with a splendid average speed of 115 mph, even completing one lap at 126 mph and beating two of the formidable Duesenbergs. This is a magnificent demonstration of the mastery of the manufacturer on Boulevard Brune. I would add, to give this feat its full significance, that Goux’s fuel consumption was only 14.2 liters per 100 kilometers, a result that does great credit to Ballot and Claudel, whose equipment was used by the Ballot team.

We know that Talbot and Talbot-Darracq, whose preparations had been delayed for various reasons, notably strikes, and whose cars were not ready, had originally decided not to race. However, as the cars were completed a few days before the race, these manufacturers, in a commendable spirit of sportsmanship, allowed them to take part. There was not enough time for fine-tuning, and and the drivers were unfamiliar with the circuit. Despite this serious handicap, which ruled out any chance of taking first place, they had a very good race, with André Boillot finishing fifth, between two Duesenbergs. Once these cars had been fine-tuned, they would be formidable competitors.

Mathis was in the same situation, his car having arrived only the day before the race. In addition, he only had a four-cylinder D,5 engine (69×100) and was only aiming to finish in a respectable position. He too was a victim of a lack of preparation; he retired on the sixth lap, hampered by insufficient front wheel steering due to the hasty installation of the brakes on those wheels. At that point, he was averaging nearly 90 mph and could have hoped to put on a very good show.

The drivers were all wonderful. Several of them showed real courage by starting the race despite injuries they had sustained earlier. Murphy, for example, was still suffering from a broken rib following his crash with Inghibert and had his torso wrapped in bandages; Wagner also had a bruised rib; Goux had cut a vein in his wrist in a collision with a cart, and his wound reopened during the race.

We must also mention André Boillot, who is deliberately following in the footsteps of his brother Georges. We saw what he did with a Talbot-Darracq; let’s add that he was vigorously applauded for changing a rear wheel in 17 seconds, which is a record. We must also mention Dubonnet, who took his car at short notice just four days before the race and, despite these unfavorable conditions, took fourth place and finished second among the Duesenbergs.

Tires and accessories. — We know that all competitors were fitted with straight side tires, and our readers know what to make of that. As for tire resistance, there has been undeniable progress. However, they were subjected to very hard work due to frequent braking.

The Pirelli tire stands out, proving to be clearly superior to the American tires. Chassagne completed 17 laps at an average speed of nearly 125 without touching his tires, which were still in perfect condition when he had to abandon the race. De Palma completed the entire course at an average speed of 118 without changing a single tire. Finally, Goux’s only stop was due to a puncture, an accident that had nothing to do with the quality of the tire. We are a long way from the Dieppe circuit in 1908, where the speeds reached and the average achieved were lower than at Le Mans.

As for the ignition, a delicate issue for eight-cylinder engines running at these speeds, we saw what to think of Delco. But the Scintilla magneto, which equipped the Ballot, also performed very well, and Scintilla brings to the magneto’s cause, in its fight against the dynamo-battery system, a boost that will enable it to resist.

Spark plugs in high-compression, high-speed engines are subjected to temperatures that few can withstand. Only two gave no cause for concern: the American AC spark plug, manufactured by Champion, and the French Sol spark plug.

The winner’s car was equipped with excellent Jaeger speedometers and tachometers, which were invaluable to Murphy in driving his race. Finally, it should be noted that a large number of competitors had entrusted their luck to SRO ball bearings, which performed admirably.

Photos.

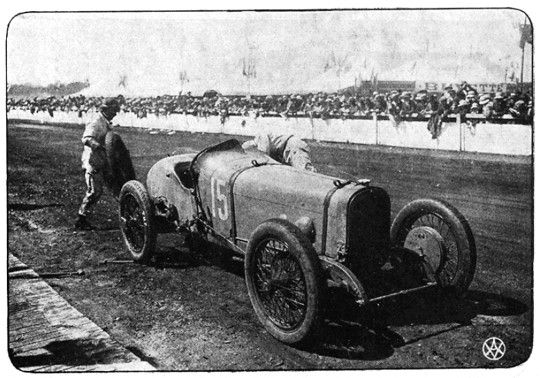

Fig. 1. — André Boillot, in a Talbot-Darracq, changes a wheel in 17 seconds.

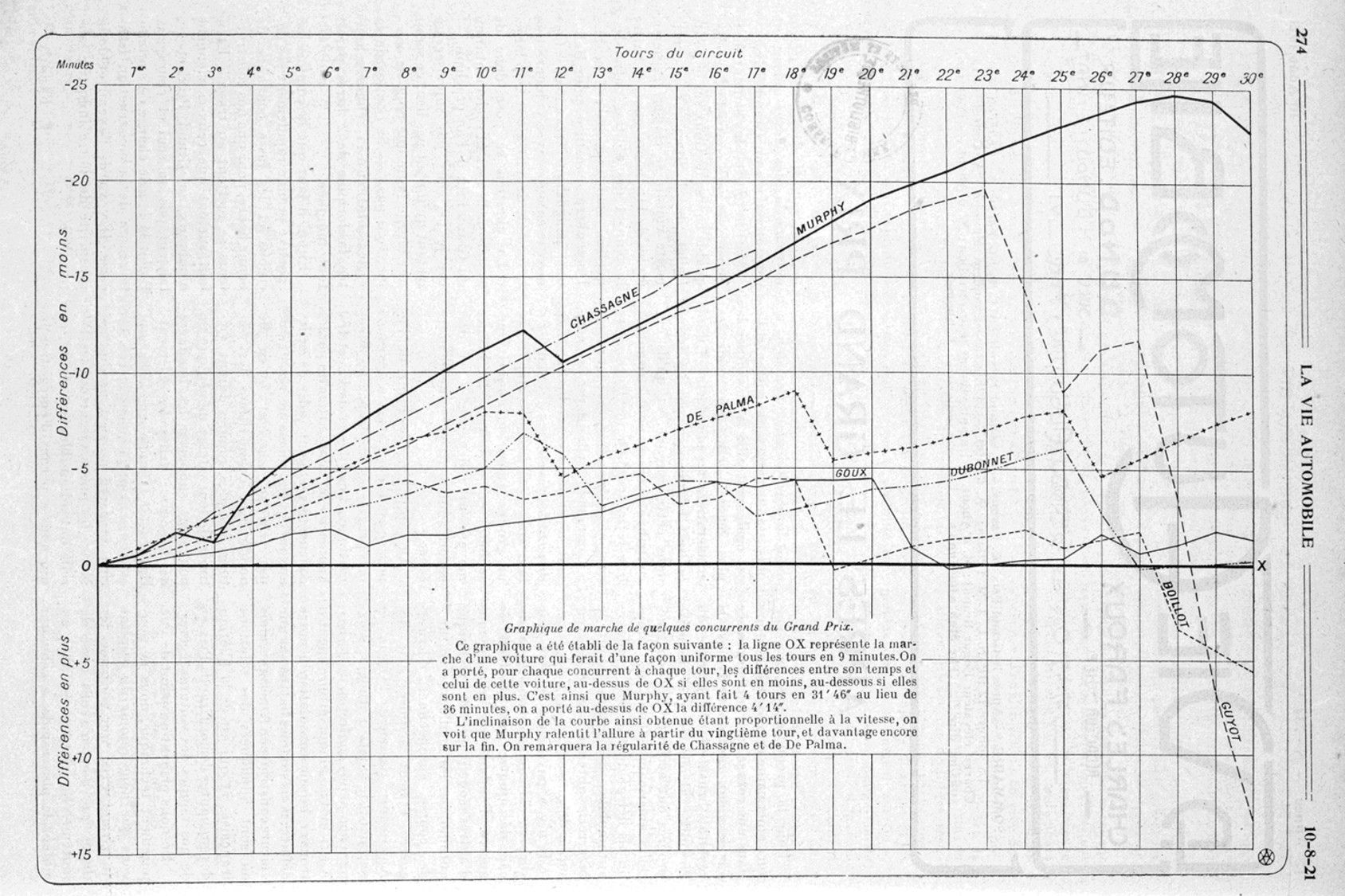

Fig. 2. — De Palma refueling.

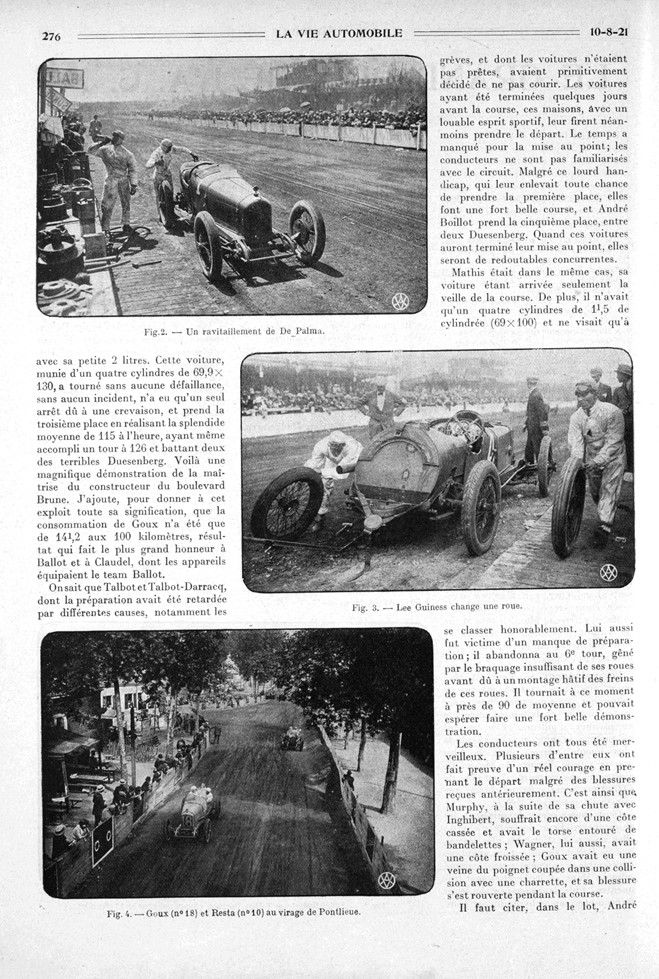

Fig. 3. — Lee Guiness changes a wheel.

Fig. 4. — Goux (No. 18) and Resta (No. 10) at the Pontlieue turn.

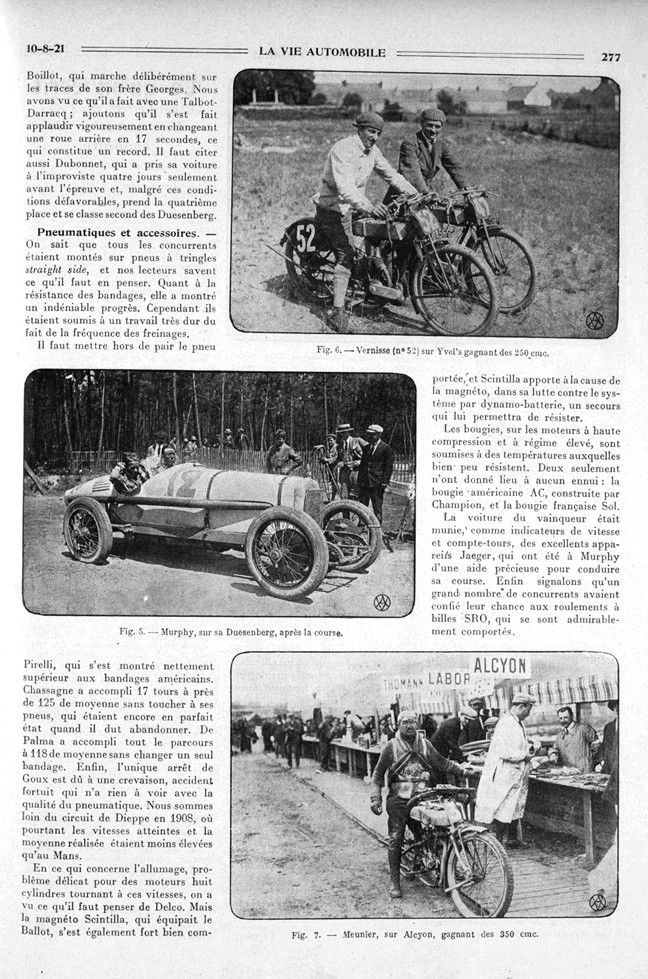

Fig. 5. — Murphy, in his Duesenberg, after the race.

Fig. 6. — Vernisse (No. 52) in Yvel’s, winner of the 250 cc class.

Fig. 7. — Meunier, in Alcyon, winner of the 350 cc class.