This Scientific American description, published a few months after the Paris-Bordeaux Trials, refers to the French article in „La Nature“. It shows not only a fine summary of some of the most signifcant carriages, as well as the graphical representation of the complete two-days race.

Text and fotos by courtesy of hathitrust.org, USA hathitrust.org, compiled by motorracinghistory.com

Scientific American Supplement, Vol. XL. No. 1023. August 10, 1895.

THE PARIS-BORDEAUX-PARIS RACE OF AUTOMOBILE CARRIAGES.

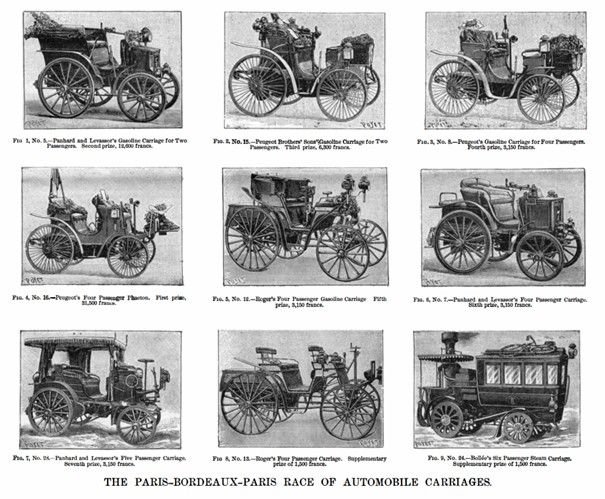

IN order to complete the notes published in our preceding numbers upon the Paris-Bordeaux-Paris race of automobile carriages of the 11th of last June, we reproduce herewith the aspect of the nine prize vehicles, as well as a complete diagram of the race.

As well known, only twenty-eight out of the forty-six vehicles that were entered presented themselves at the exposition at the time desired in order to take part in the race, and but twenty-two effectively took part in it. Out of the twenty-two vehicles that started from the control of Versailles, twelve made a regular turn at Bordeaux before the closing of the register, and nine made the complete trip in less than a hundred hours. Out of these nine carriages, eight were actuated by naphtha or gasoline motors and one, that of Mr. Bollée, dating from 1880, by steam. It was an unquestionable and unquestioned triumph of the gasoline motor in a crude test that gave rise to many doubts as to the endurance of the drivers and of the very complex and delicate parts united upon an automobile carriage.

A description of all these carriages would present but a mediocre interest, and the more so in that they do not differ essentially, as may be seen, from those that won the prizes last year at the same season in the race of horseless carriages organized by the Petit Journal. We reproduce all these carriages in the order of their arrival at Paris and must state the prize that was awarded to each of them by the committee.

It will be remarked that carriage No. 5 (Fig. 1) of Messrs. Panhard and Levassor, which was the first to reach Paris, and far ahead of the others, obtained only the second prize. The reason of this was that the first prize, according to the terms of the race, could be a warded only to a carriage for four or more passengers. Carriage No. 16, which was the fourth to arrive, obtained the first prize, because, taking account of the hours of starting. it took two minutes less than carriage No. 8 to make the trip.

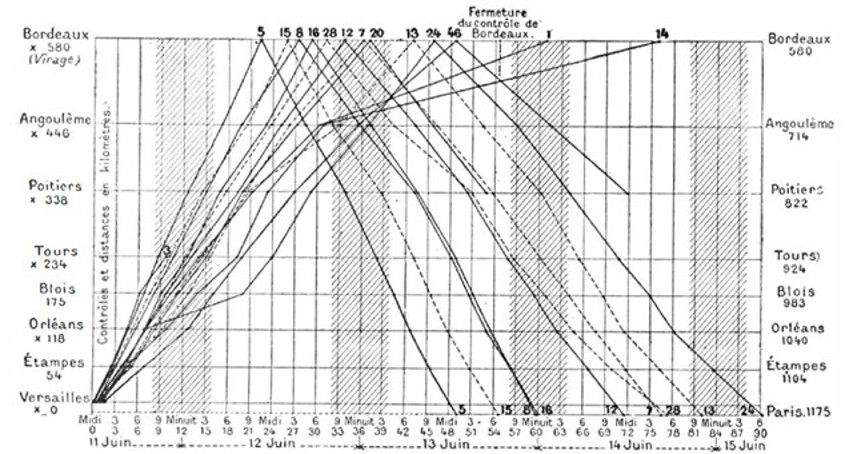

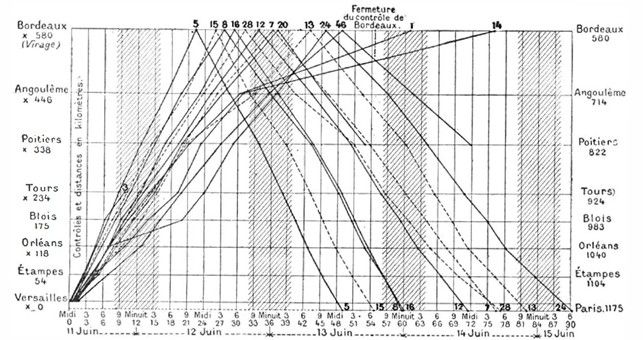

The complete diagram of the race given in Fig. 10 brings clearly into relief the principal incidents and accidents of it, the greater or less regularity of running of the different carriages, the crossing points and their times, etc.

It is seen, for example, that the last carriage that reached Bordeaux made its turn at the very moment at which carriage No. 5 arrived at Paris, having made the great distance of 705 miles in 48 hours 48 minutes. The running of all the prize gasoline carriages was perfectly characteristic.

Their diagram represents an inverted V, the two legs of which are so much the more rectilinear in proportion as the speed was the more uniform, and so much the closer together in proportion as the speed was greater. From this point of view the run of No. 5 was truly irreproachable. The diagram sufficiently shows, without. the necessity of dwelling upon it, the carriages of which not so much could be said.

A few technical facts suggest themselves from the results of this race, and it has seemed to us of interest to set them forth upon the score of useful information, in view of the progress that automobile locomotion is destined to make in the near future.

Upon the whole, it was the lightest vehicles that behaved the best on the road, and this fact, now indisputably established, proves the superiority of gasoline and naphtha over any other motive power at present known. This, in fact, is because, all things otherwise equal, it suffices to carry 14 ounces of gasoline to produce one horsepower for one hour, while steam requires at least 6’5 pounds of coal and from 40 to 45 pounds of water. As for electric accumulators, it would require more than 220 pounds to obtain the same power during the same time.

For a run of five or six hours a few quarts of gasoline suffice, and the weight of the fuel supply becomes entirely negligible before that of the vehicle, motor and passengers. The same is not the case with steam, the generator of which represents, aside from the supply of water and coal, considerable of a dead weight, while electric accumulators are as yet very inferior from this standpoint, since the apparatus, which is very heavy of itself, expends the most available part of its energy in its own propulsion.

Light vehicles permit of benefiting by other appreciable advantages, such as the use of rubber tires, with which all the prize carriages were provided, and even of pneumatic tires, as in carriage No. 46. of Mr. Michelin. which made the trip of 720 miles without any accident to the wheels, despite the weight of 2, 375 pounds that it supported. Ball bearings. which have already been applied to the Peugeot carriages, and with which no steam carriage, we believe, was provided, also contributed to the success of the gasoline vehicles in a certain measure.

As for the bicycles, they are of too recent creation, and the test has been too crude to permit of any conclusion whatever being drawn from their want of success. All the speedy steam carriages met with accidents that seem to indicate that the weight of these vehicles, necessitated by the very use of steam, divests them of the qualities that we find on the contrary. In all the gasoline carriages. Carriage No. 24, of Mr. Amedee Bollée (Fig. 9), which is slower and more staid, on account of its respectable age and the purpose for which it was constructed, did not escape accidents; and it was a truly extraordinary thing that the son of Mr. Bollée. the driver of the vehicle, did in repairing in situ. with merely the resources at bis disposal upon the carriage. a gearing broken in t wo pieces, by cutting the cheeks out of a useless piece of iron plate, using old nails for rivets. reforging the broken links on the spot, thus losing 22 h ours in a single repair and reaching Paris before the close of the control register.

Accidents, incidents and picturesqueness were not wanting in this race without precedent, and it would require a volume which someone will probably write one of these days) to perpetuate the remembrance of it. What suggestive reflections are not inspired by the 1895 bicycle lying upon the Bollée carriage of 1880 (Fig. 9); by the bag of ice thrown at the entrance of Étampes into a petroleum carriage for cooling the cylinders; by the bouquets thrown with more enthusiasm than prudence at the unfortunate drivers of the carriages, who were thus bombarded with projectiles having a relative velocity of from 25 to 30 mile an hour; by the walking up of steep gradients in pushing the vehicle ahead; by the carmen who did not assert their rights and by the dogs that crossed the road and upset the carriage in getting crushed!

Despite all such incidents, or rather on account of such incidents, the Paris-Bordeaux-Paris race will remain a memorable event and will mark the date of the advent of a new sport which it seems, however. Useless to repeat under conditions so severe and difficult. For our engravings we are indebted to La Nature.

Picture captions.

FIG 10 – Graphic Trace of the Paris-Bordeaux-Paris Race of Automobile Carriages. The times are shown in abscises and the distance in ordinates.

The figures given beneath the name of each control indicate, in kilometers, the ground passed over from the start at Versailles in going (column to the left) and returning (column to the right). The curves 1 and 3 relate to De Doin’s steam carriages, 14 to the Duncan and Suberbie bicycle, and 20 to one of Serpollet’s steam carriages. The shaded bands represent nights.