Text and photos compiled by motorracingistory.com, with courtesy of hathitrust.org / Digital Library, USA.

The Motor World. Vol. X, No. 17, Thursday, July 20, 1905 page 735-750

How Thery Won the Bennett Cup the Second Time.

Laschamps, July 5. – If, as we are led to believe by the decision of the French Automobile Club, the Bennett cup has had its day, the celebrated trophy has at least gone out in something of an apotheosis.

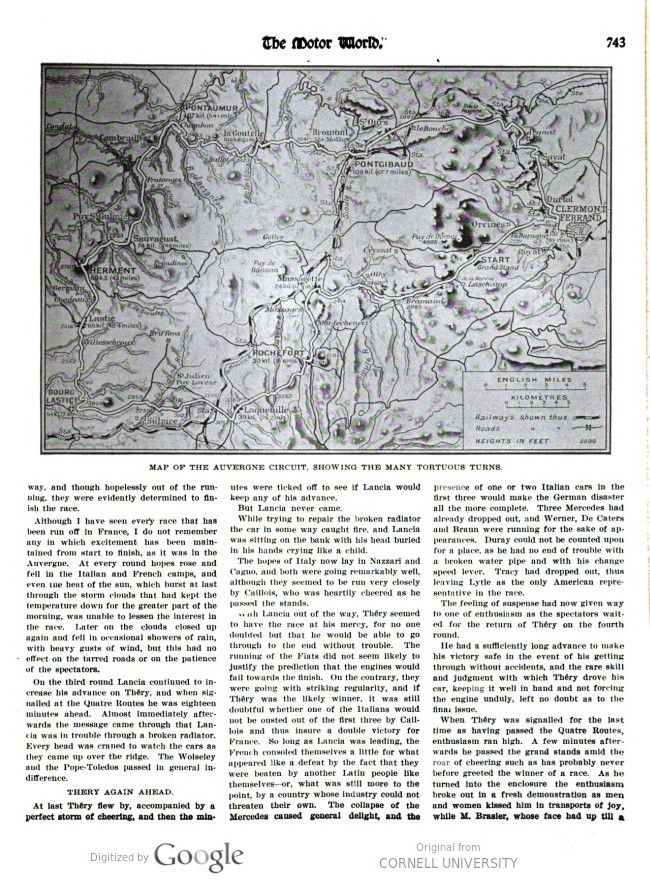

It has had a strange career, beginning amid a general indifference and ending in a glorious triumph, and by accurately reflecting the industry, especially in its international aspect, the sensational rise and fall of the cup will go down as one of the most interesting pages in automobile history. Everything in the Auvergne contest tended to raise the event above an ordinary level. It was paradoxical to begin with, for who could expect that high-speed cars could race over a course where racing appeared impossible?

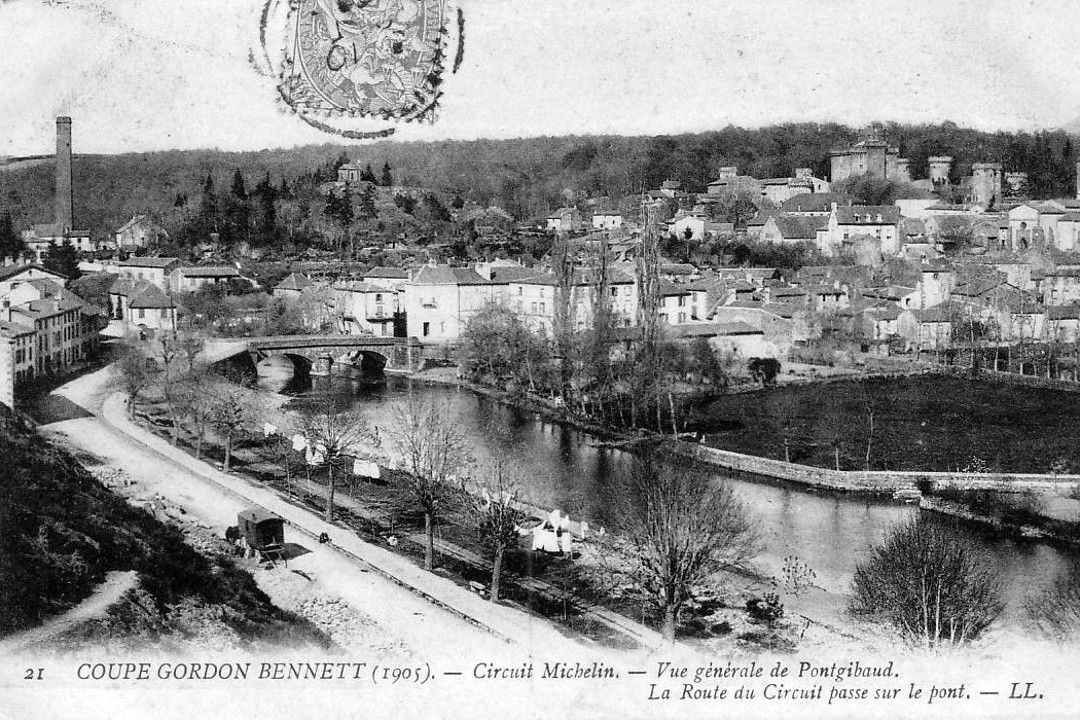

The best comparison to be made is that the Auvergne circuit resembles other roads as much as a steeplechase course does a flat track, with the difference that the obstacles are formed of hills and bends.

Those bends!

What a terror they inspire with their twists and turns, even among the most case hardened drivers, but as familiarity with danger breeds something akin to contempt, so the competitors ended by looking upon the situation philosophically, arguing that, after all, they had only to find out the safe limit at which they could drive their cars to go through this formidable contest without breaking their necks. Thus, the presence of danger inspired a caution which made the most perilous course safer than any that had preceded it, and while the eliminating trials only saw two cars smashed up, the Bennett race was devoid of serious accident of any kind. And now for the story.

How things fared for the visitors at Clermont-Ferrand and Royat, I do not know. Preparations had been made to receive thousands of people, and in justice to the much-maligned inhabitants of the Auvergne, it must be confessed that the authorities were successful in preventing hotel keepers and others from charging too dearly for their hospitality. At the same time, I am afraid that the crowd did not come so thickly as had been expected, despite the attractions offered by Clermont and Royat, and it would be an insult to Homburg to attempt to compare the preparations of the Auvergne with those carried out last year on the Taunus. There was an entire absence of that social element which gave so much prominence to the race in Germany.

The only legitimate source of complaint for visitors who merely went to see the race and did not look for side attractions was the difficulty of getting to and from the course, and it was for this reason that I selected one of the two little hotels or auberges that lie nestled in a pass just below the Puy de Dome. The only society in this charming spot was composed of a company of fourteen gentlemen who depended for a livelihood upon the agility of their fingers and their predilection for entertaining strangers with a game for which three cards constitute the stock in trade. Many a visitor was relieved of his pocketbook during the race.

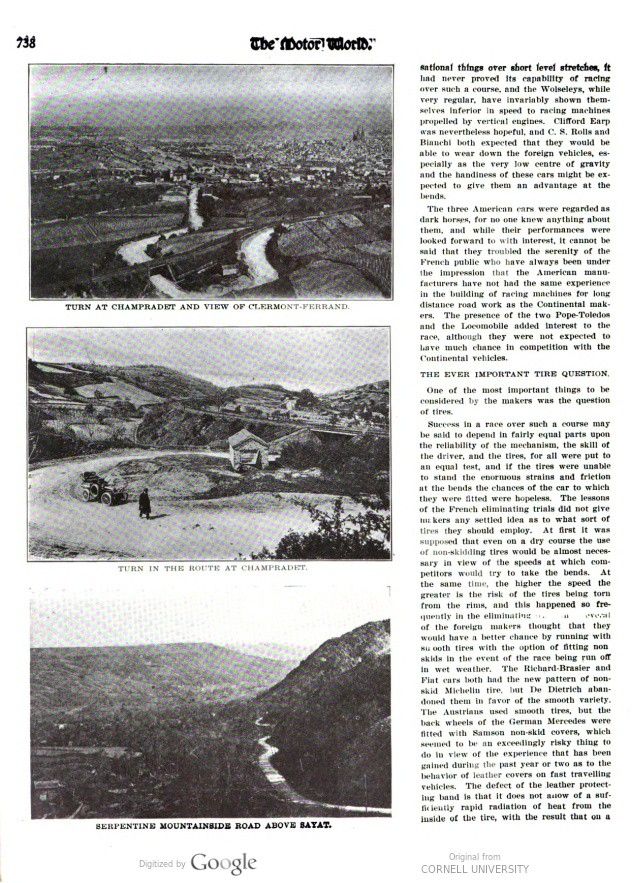

From the Puy de Dome the plain of Laschamps stretches out below, with the mountains rolling away in the distance, and in the early morning the mists tone down the distant ranges like a gray rolling mass of billows, while in the foreground and middle distance the dome shaped extinct volcanoes are covered with a black carpeting of pines. It is impressive, but entirely without charm.

The Auvergne lacks color.

Through the heather covered plain of Laschamps, in which not a house or habitation of any kind is to be seen, winds the road, coming up apparently out of a hollow and then descending behind the shoulder of a hill, while if we look to the other side, a thin, winding streak is pointed out as the circuit, like a stream which is trying to find its level. Built up of mountains and valleys, tormented by fire and scored by rushing waters in countless ages past, the Auvergne looks the most unlikely spot on the face of the earth that could possibly be selected for a motor car race.

A CYCLONE FOR A CURTAIN RAISER.

Even the elements seemed to conspire against the race.

On the day before, while the weighing was in progress, a cyclone descended on the plain threatening destruction everywhere. After a close morning the air became stifling and heavy black clouds rolled up over the mountain tops. A blinding cloud of brown sand was driven through the enclosure by a roaring wind, which swept under one of the tents sheltering the cars. The tent dropped down with a crash, while the canvas flapped in the wind. Then there was a calm, followed by another roar and a crash, as the weighing tent toppled over, the people inside scuttling out like rabbits from a hole. A third time the cyclone hurled its fury around the plain, and the remaining tent covering the cars heeled over, while the canvas roofs were stripped off the stands like paper. Having wrought as much havoc as it could, the wind went to its rest, and after an exciting quarter of an hour, when it seemed as if nothing would remain standing, the officials were able to resume the weighing.

About the cars themselves, there is not much to be said. The construction of motor vehicles has now so far reached finality that even in racing machines there is no longer any notable departure from ordinary designs. All the vehicles were developments of the standard patterns, from which they only differed in horsepower and in the dimensions of frames and strength of parts which had to be specially calculated for the Auvergne course. Somehow there was a sense of handiness about the Richard-Brasier cars, which seemed to make them especially suited for the circuit, and the strength of the chassis, with its secondary tubular frame and the concentrating of the weight as nearly as possible to the centre, certainly gave a stability to the Brasier vehicles that allowed of their taking the bends more easily than most of the other cars, while the Brasier engines have given such proofs of reliability that the vehicles started as prime favorites, the one driven by Théry, of course, being expected to win. This quality of handiness seemed to be wanting in the De Dietrich car, which was more remarkable for its sense of power, and there is no doubt that on a straightaway course it would prove very fast, but the somewhat massive appearance of the car was rather against it over such a course as that selected in the Auvergne. Ine design of the De Dietrich engine follows the now almost general practice of casting the cylinders in pairs, but instead of having the jacket casing cast with the cylinders, it is composed of plates bolted on each pair so as to facilitate a rapid circulation of water, and at the same time allow of easy inspection. The De Dietrich engine is a thoroughly good one, and, as was the case with most of the others, it did not give the slightest trouble during the race.

At first the French thought that the only competitor they had to fear was the Mercedes, not so much on account of any superiority of these vehicles as of the fact that their chances were increased by the running of six Mercedes, three to represent Germany and three Austria. In a general way the Mercedes certainly appeared to have an advantage over such a course alike as regards their handiness, the rapidity in picking up speed, and the speeds at which they traveled on level stretches. It is true that the cars rarely had a chance of going all out, but nevertheless it was thought that, coming with such a reputation and having an ad- vantage of numbers on their side, they would prove very formidable competitors.

FRENCH FEAR OF THE ITALIAN CARS.

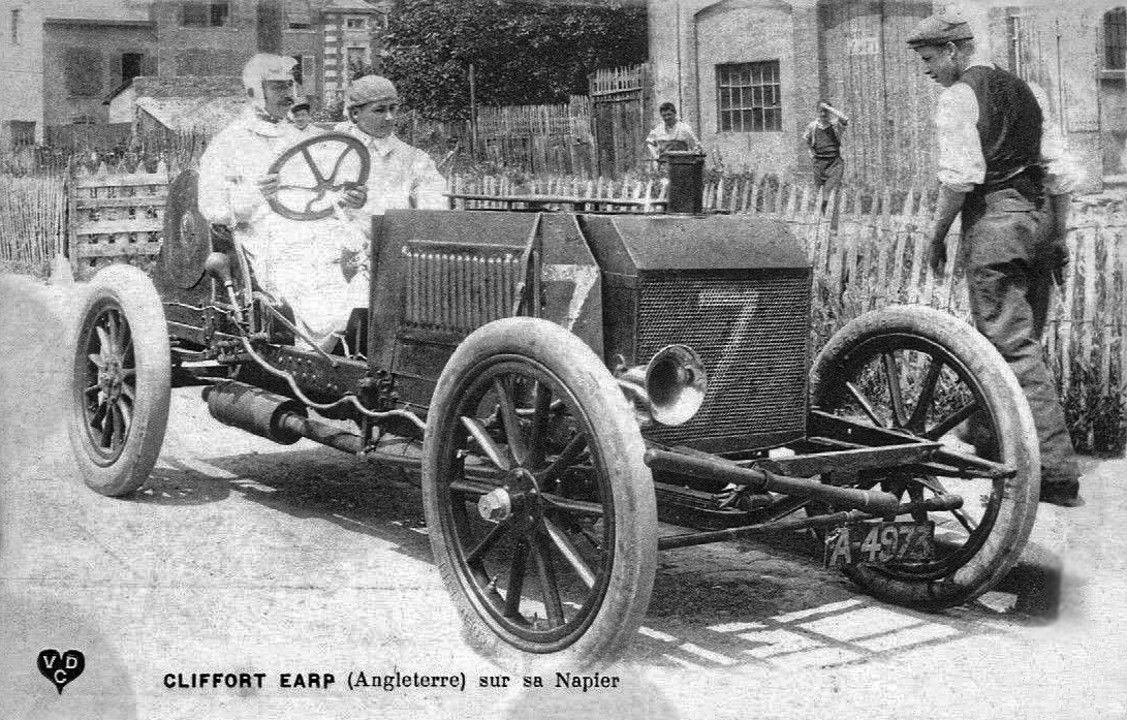

It was only later that the French began to look somewhat anxiously upon the Fiats, for they had a very strong Italian following on the course, who seemed to be absolutely confident in the victory of Lancia, while it was expected that the two other Italian cars would run him very closely. It was evident that the Italians had been care- fully testing the Fiats and knew exactly what they could do over the course, and it must be admitted that an inspection of these cars showed that there was plenty of ground for this confidence. None of the vehicles gave evidence of more solid and careful construction, and that they were speedy there can be no doubt, while they had a further advantage in being fitted with the new multiple plate clutch which favors the picking up of speed on leaving the bends and turnings. The English cars came with a second-rate reputation, for while the six cylinder Napier, driven by Clifford Earp, had done some sensational things over short level stretches, it had never proved its capability of racing over such a course, and the Wolseleys, while very regular, have invariably shown themselves inferior in speed to racing machines propelled by vertical engines. Clifford Earp was nevertheless hopeful, and C. S. Rolls and Bianchi both expected that they would be able to wear down the foreign vehicles, especially as the very low centre of gravity and the handiness of these cars might be expected to give them an advantage at the bends.

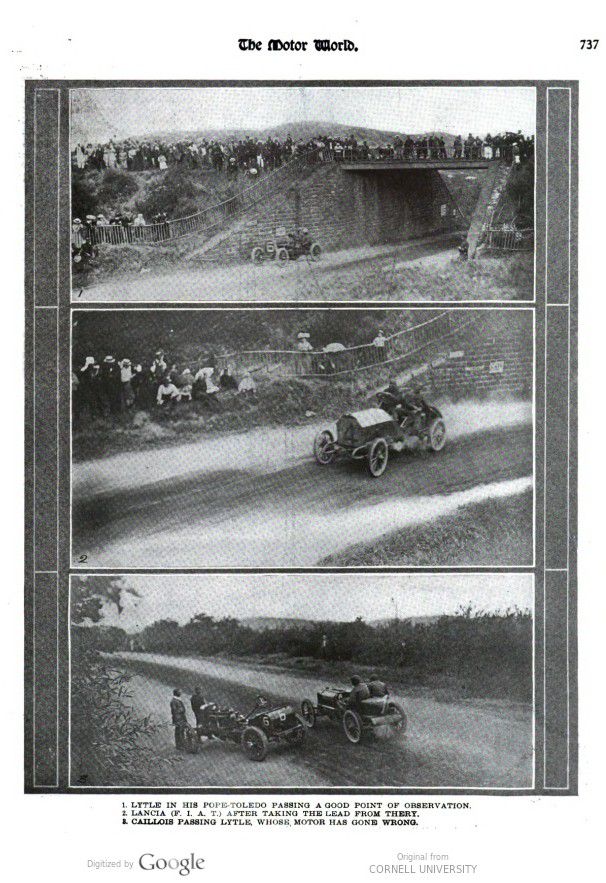

The three American cars were regarded as dark horses, for no one knew anything about them, and while their performances were looked forward to with interest, it cannot be said that they troubled the serenity of the French public who have always been under the impression that the American manufacturers have not had the same experience in the building of racing machines for long distance road work as the Continental makers. The presence of the two Pope-Toledo’s and the Locomobile added interest to the race, although they were not expected to have much chance in competition with the Continental vehicles.

THE EVER IMPORTANT TIRE QUESTION.

One of the most important things to be considered by the makers was the question of tires.

Success in a race over such a course may be said to depend in fairly equal parts upon the reliability of the mechanism, the skill of the driver, and the tires, for all were put to an equal test, and if the tires were unable to stand the enormous strains and friction at the bends the chances of the car to which they were fitted were hopeless. The lessons of the French eliminating trials did not give Inkers any settled idea as to what sort of tires they should employ. At first it was supposed that even on a dry course the use of non-skidding tires would be almost necessary in view of the speeds at which competitors would try to take the bends. At the same time, the higher the speed the greater is the risk of the tires being torn from the rims, and this happened so frequently in the eliminating ***. Several of the foreign makers thought that they would have a better chance by running with smooth tires with the option of fitting non skids in the event of the race being run off in wet weather. The Richard-Brasier and Fiat cars both had the new pattern of non-skid Michelin tire, but De Dietrich abandoned them in favor of the smooth variety. The Austrians used smooth tires, but the back wheels of the German Mercedes were fitted with Samson non-skid covers, which seemed to be an exceedingly risky thing to do in view of the experience that has been gained during the past year or two as to the behavior of leather covers on fast travelling vehicles. The defect of the leather protecting band is that it does not allow of a sufficiently rapid radiation of heat from the inside of the tire, with the result that on a very fast car the heat stored up inside disintegrates the rubber and causes the tire to burst in a very short time. This was probably the case with the German Mercedes, for, as we shall see, one of the most sensational things of the race was the collapse of the Mercedes cars, principally through tire troubles.

HOW SPECTATORS GOT THERE.

The morning of the race broke with a prospect of a fairly fine day, although when we rose at 4 o’clock in the morning the weather gave signs of approaching storms, which, however, seemed likely to hold over until the race was ended. As we descended the mountain pass and tramped over the heather covered plain, there was little to show that we were on the eve of the greatest automobile contest that has yet been held, for the stands that stood in the centre of the plain alone showed that any preparations had been made for the contest.

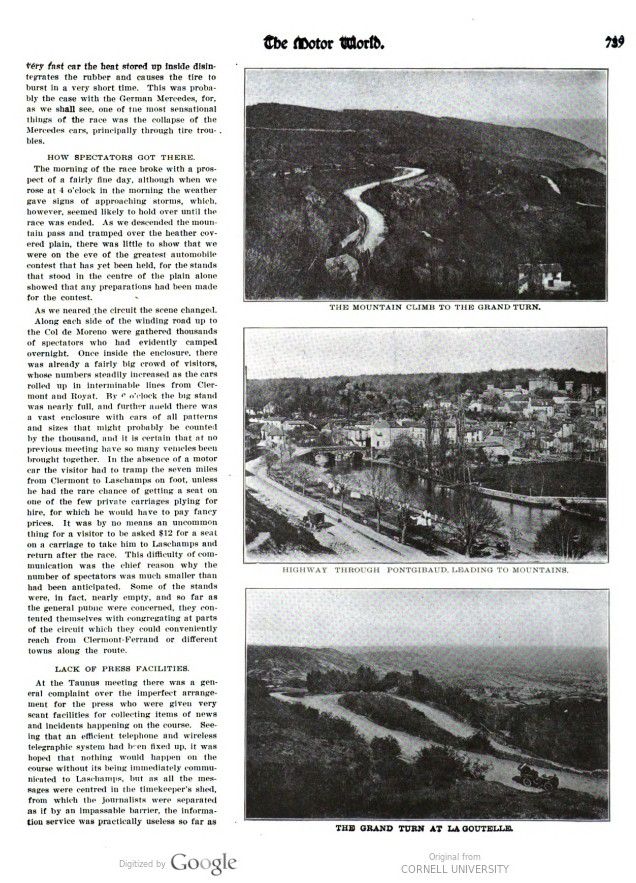

As we neared the circuit the scene changed. Along each side of the winding road up to the Col de Moreno were gathered thousands of spectators who had evidently camped overnight. Once inside the enclosure, there was already a fairly big crowd of visitors, whose numbers steadily increased as the cars rolled up in interminable lines from Clermont and Royat. By * o’clock the big stand was nearly full, and further ahead there was a vast enclosure with cars of all patterns and sizes that might probably be counted by the thousand, and it is certain that at no previous meeting have so many vehicles been brought together. In the absence of a motor car the visitor had to tramp the seven miles from Clermont to Laschamps on foot, unless he had the rare chance of getting a seat on one of the few private carriages plying for hire, for which he would have to pay fancy prices. It was by no means an uncommon thing for a visitor to be asked $12 for a seat on a carriage to take him to Laschamps and return after the race. This difficulty of communication was the chief reason why the number of spectators was much smaller than had been anticipated. Some of the stands were, in fact, nearly empty, and so far as the general public were concerned, they contented themselves with congregating at parts of the circuit which they could conveniently reach from Clermont-Ferrand or different towns along the route.

LACK OF PRESS FACILITIES.

At the Taunus meeting there was a general complaint over the imperfect arrangement for the press who were given very scant facilities for collecting items of news and incidents happening on the course. Seeing that an efficient telephone and wireless telegraphic system had been fixed up, it was hoped that nothing would happen on the course without it being immediately communicated to Laschamps, but as all the messages were centred in the timekeeper’s shed, from which the journalists were separated as if by an impassable barrier, the information service was practically useless so far as the pressmen were concerned. It was a trying task, eking out bits of news at second hand, and as in the absence of official messages there were plenty of startling rumors during the race, the reporter was worried over the fear of missing something and of giving publication to matters on the strength of rumor that had no basis in fact. The only thing he could rely on was the telegraph board giving the gross times as each car finished a lap, and as there were three points along the route at which cars were stopped in the event of their overlapping each other, it was impossible to get an approximate idea of the placings, while the official results were not obtainable until about 6 o’clock in the evening.

THE ORDER OF THE SEND-OFF.

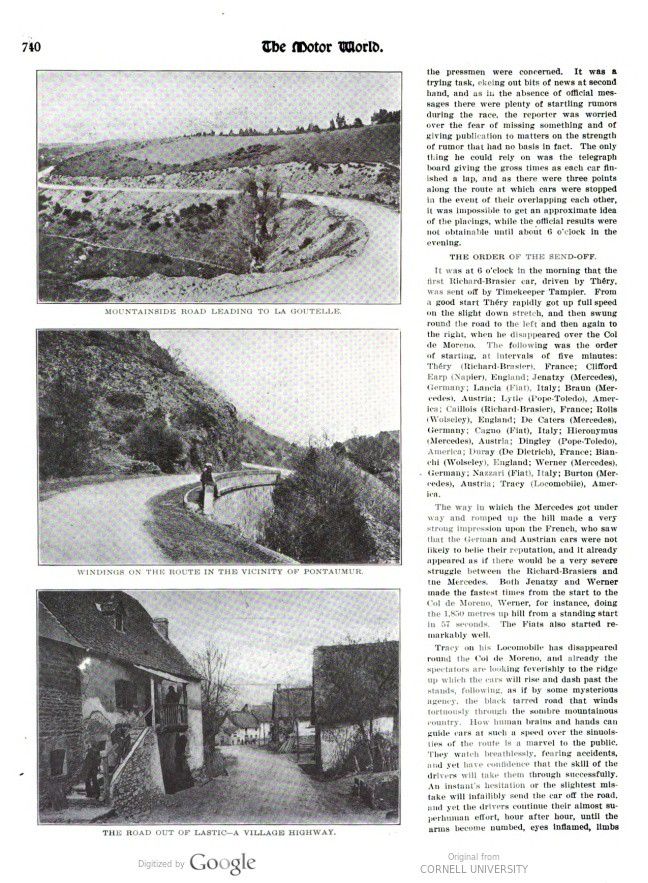

It was at 6 o’clock in the morning that the first Richard-Brasier car, driven by Théry, was sent off by Timekeeper Tampier. From a good start Théry rapidly got up full speed on the slight down stretch, and then swung round the road to the left and then again to the right, when he disappeared over the Col de Moreno. The following was the order of starting, at intervals of five minutes: Théry (Richard-Brasier), France; Clifford Earp (Napier), England; Jenatzy (Mercedes), Germany; Lancia (Fiat), Italy; Braun (Mercedes), Austria; Lytle (Pope-Toledo), America; Caillois (Richard-Brasier), France; Rolls (Wolseley), England; De Caters (Mercedes), Germany; Cagno (Fiat), Italy; Hieronymus (Mercedes), Austria; Dingley (Pope-Toledo), America; Duray (De Dietrich), France; Bianchi (Wolseley), England; Werner (Mercedes), Germany; Nazzari (Fiat), Italy; Burton (Mercedes), Austria; Tracy (Locomobile), America.

The way in which the Mercedes got under way and romped up the hill made a very strong impression upon the French, who saw that the German and Austrian cars were not likely to belie their reputation, and it already appeared as if there would be a very severe struggle between the Richard-Brasiers and the Mercedes. Both Jenatzy and Werner made the fastest times from the start to the Col de Moreno, Werner, for instance, doing the 1,850 metres uphill from a standing start in 57 seconds. The Fiats also started remarkably well.

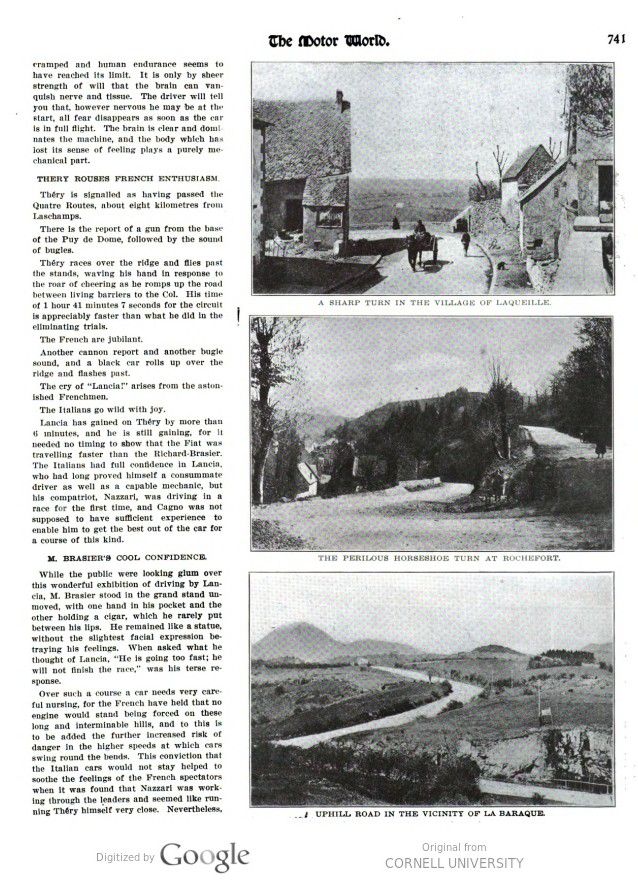

Tracy on his Locomobile has disappeared round the Col de Moreno, and already the spectators are looking feverishly to the ridge up which the cars will rise and dash past the stands, following, as if by some mysterious agency, the black tarred road that winds tortuously through the sombre mountainous country. How human brains and hands can guide cars at such a speed over the sinuosity’s of the route is a marvel to the public. They watch breathlessly, fearing accidents, and yet have confidence that the skill of the drivers will take them through successfully. An instant’s hesitation or the slightest mis- take will infallibly send the car off the road, and yet the drivers continue their almost superhuman effort, hour after hour, until the arms become numbed, eyes inflamed, limbs cramped and human endurance seems to have reached its limit. It is only by sheer strength of will that the brain can vanquish nerve and tissue. The driver will tell you that, however nervous he may be at the start, all fear disappears as soon as the car is in full flight. The brain is clear and dominates the machine, and the body which has lost its sense of feeling plays a purely mechanical part.

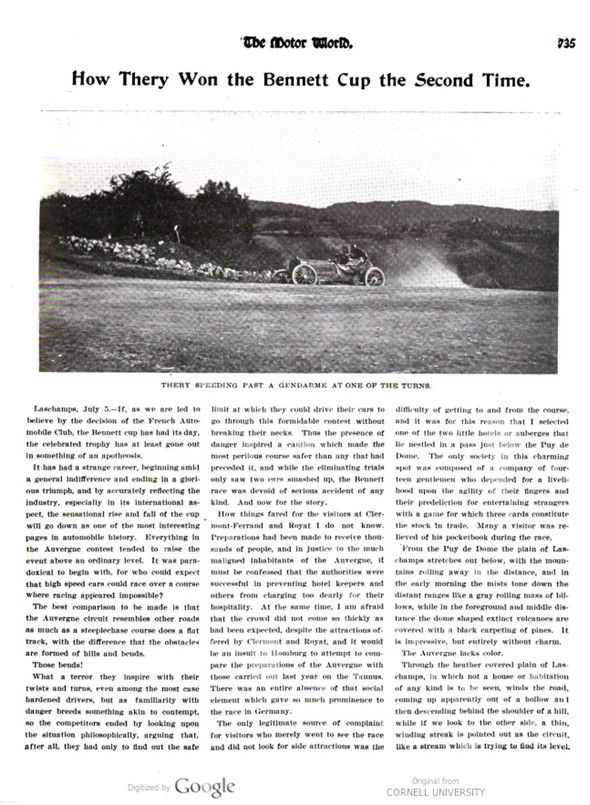

THERY ROUSES FRENCH ENTHUSIASM.

Théry is signaled as having passed the Quatre Routes, about eight kilometres from Laschamps.

There is the report of a gun from the base of the Puy de Dome, followed by the sound of bugles.

Théry races over the ridge and flies past the stands, waving his hand in response to the roar of cheering as he romps up the road between living barriers to the Col. His time of 1 hour 41 minutes 7 seconds for the circuit is appreciably faster than what he did in the eliminating trials.

The French are jubilant.

Another cannon report and another bugle sound, and a black car rolls up over the ridge and flashes past.

The cry of „Lancia!“ arises from the astonished Frenchmen.

The Italians go wild with joy.

Lancia has gained on Théry by more than 6 minutes, and he is still gaining, for it needed no timing to show that the Fiat was travelling faster than the Richard-Brasier. The Italians had full confidence in Lancia, who had long proved himself a consummate driver as well as a capable mechanic, but his compatriot, Nazzari, was driving in a race for the first time, and Cagno was not supposed to have sufficient experience to enable him to get the best out of the car for a course of this kind.

M. BRASIER’S COOL CONFIDENCE.

While the public were looking glum over this wonderful exhibition of driving by Lancia, M. Brasier stood in the grandstand unmoved, with one hand in his pocket and the other holding a cigar, which he rarely put between his lips. He remained like a statue, without the slightest facial expression betraying his feelings. When asked what he thought of Lancia, „He is going too fast; he I will not finish the race,“ was his terse response.

Over such a course a car needs very careful nursing, for the French have held that no engine would stand being forced on these long and interminable hills, and to this is to be added the further increased risk of danger in the higher speeds at which cars swing round the bends. This conviction that the Italian cars would not stay helped to soothe the feelings of the French spectators when it was found that Nazzari was working through the leaders and seemed like running Théry himself very close. Nevertheless,