„A pictorial history of the American automobile, as seen in Motor Magazine 1903-1953“, by Philip Van Doren Stern. This 1953 book explains a large part of the first fifty years American automotive history, covered in over just more than 250 pages. This part below deals with the 1895 November Times-Herald contest in Chicago.

Text and photos compiled by motorracingistory.com, with courtesy of hathitrust.org, USA.

A pictorial history of the American automobile, Philip Van Doren Stern, Viking Press, New York, 1953, Section Automobile Racing (page 208 – 209)

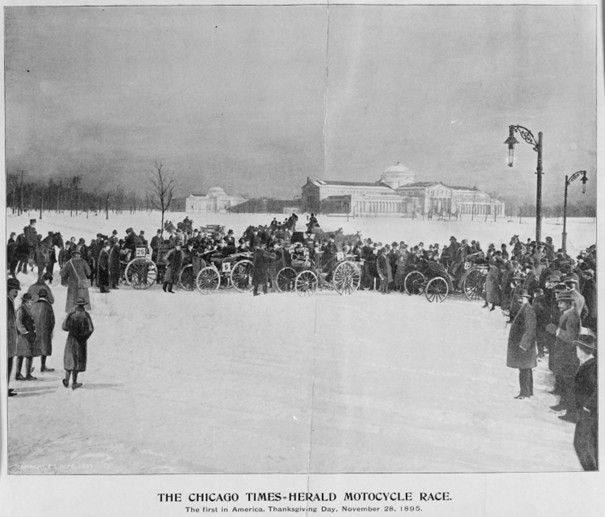

THE FIRST AMERICAN AUTOMOBILE RACE: 1895

The Times-Herald Contest in Chicago

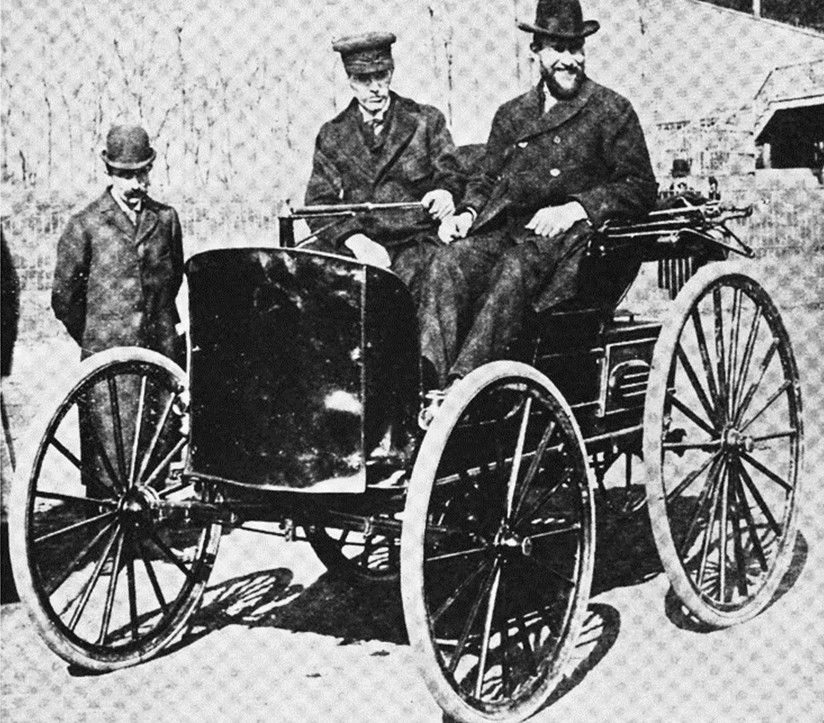

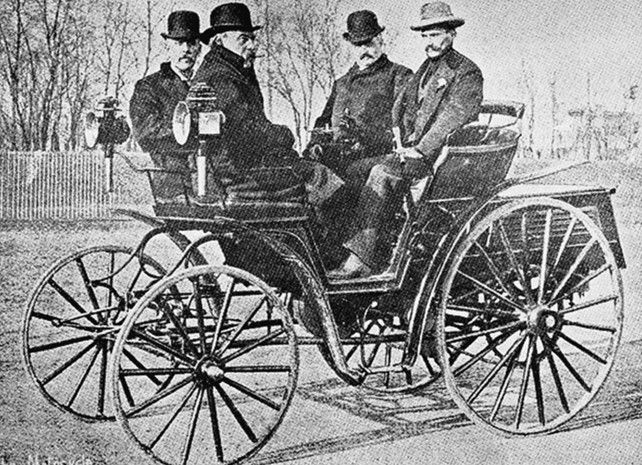

The Paris-Rouen Race had a catalytic effect throughout the world. Inventors and mechanics everywhere began building experimental cars. The Chicago World’s Fair in 1893, at which a Daimler car was exhibited, also increased interest in the automobile in America. William Steinway, the piano manufacturer, obtained the Daimler rights for this country. He built Daimler-engined automobiles and launches for several years but lost more than half a million dollars on the venture.

In Chicago, H. H. Kohlsaat had recently purchased the Times-Herald and was looking for ways to promote his newspaper. One of his employees, Frederick Upham Adams, suggested that Kohlsaat hold a contest for the new horseless carriages. Adams‘ persuasiveness won Kohlsaat over, and a public announcement was made, stating that a race was to be held in Chicago on July 4, 1895. A $5000 purse was offered, $2000 of which was to go to the winner, with the rest to be divided among the runners-up. More than eighty applications were received from all over the country, but it soon became evident that most of the American automobiles which were then under construction would not be finished by July, so the race had to be postponed until early November and then again to Thanksgiving Day, November 28.

Word arrived from France in June of the 700-mile Paris-to-Bordeaux-and-return race which had been won by a Panhard with three Peugeots as runners-up. In order to keep up public interest for his forthcoming Thanksgiving Day race, Kohlsaat offered a prize of $500 for a new name for horseless carriages (see page 32).

On Thanksgiving Day eve, an eight-inch fall of wet snow blanketed the whole Chicago area. The Motocycle, a new and short-lived automobile magazine gave a contemporary account of the contest: „On the evening before the race, eleven competitors declared they would start, but when the motocycles were sent on their fifty-four mile run, only six had appeared at Jackson Park and Midway Plaisance [at 8:30 A.M.] They were:

“Duryea Motor Wagon Company, Springfield, Mass.

“De La Vergne Refrigerating Machine Company, New York. (Benz motor]

“Morris and Salom, Philadelphia, electric.

“H. Mueller and Company, Decatur, Ill. [Benz motor]

“R. H. Macy Company, New York. [Benz motor]

“Sturgess Electric Motocycle, Chicago, electric.

“Haynes and Apperson, of Kokomo, Ind., started for Jackson Park early in the morning. In making a turn to avoid a street car, the forward wheel of the motocycle was smashed, so they had to give up the race. A. Baushke and Brother, of Benton Harbor, Mich., failed to get their wagon [to Chicago) in time. Something snapped in the steering gear of the wagon belonging to Max Hertel of Chicago. A. C. Ames of South Chicago and George W. Lewis of Chicago could not get ready in time.

“Along the route and at the turning corners from Jackson Park to Evanston hundreds waited. The boulevards were crowded with rigs and cutters, dashing up and down over the snow, looking for the horseless carriages.

“Ready!”” shouted Judge Kimball, as he stood, watch in hand, at the side of the Duryea wagon. J. F. Duryea leaped into the wagon, followed by Arthur W. White, the umpire. At 8:55 o’clock the word ‚Go‘ was uttered, and the motocycle passed through the crowd. A minute later the Benz wagon of the De La Vergne Refrigerating Machine Company started. The Benz motor proved unequal to getting over the bad road from the starting point to Fifty-Fifth Street. The wheels slipped around in the snow but failed to go forward. So, the wagon was shoved over the deep snow to a better part of the road.

“Macy’s wagon started in good shape at 8:59 o’clock. The Sturgess electric motocycle left at 9:01; the Morris and Salom electric wagon left a minute later. The Mueller gasoline motocycle did not start until 10:06.

“In the parkway every drive was filled with swell turn- outs, occupied by capitalists who may wish motocycles for next summer, and inventors who were skeptical of the ability of the machines to overcome the slush and snow of the bright day.

“The run through South Park was uneventful for all the machines, but the snow made the De La Vergne people quit the contest to await a more favorable time. There were a thousand people on Fifty-Fifth Boulevard to cheer the motors as they headed for Michigan Avenue. About 10,000 people stood on the walks between Fifty-First Street and the Auditorium Hotel on Michigan Avenue.

“The judges had come to the Leland Hotel where they saw the Duryea pass. The Macy … overtook the Duryea at Rush and Erie, where the latter temporarily broke down. After passing through Lincoln Park, the Duryea was still behind the Macy motocycle, but it was making quick time to pass its rival. At Evanston the Macy machine was slightly in the lead. After they had turned north on Forest Avenue, the Duryea was pressing the leader hard, and in accordance with the rules of the contest, the Macy drew to one side to allow the faster competitor to pass. People along Forest Avenue applauded the unusual sight of one horseless carriage forging ahead of a rival.

“While coming back, the Macy carriage met a hack which would not give the right of way. The tire of the motocycle slipped, and its left front wheel collided with the rear wheel of the hack. Four spokes were badly chipped, and the steering gear was bent so as to be almost useless. By keeping on the car tracks, it managed to reach the second relay station a mile farther on. The Mueller wagon passed the Macy while the New York machine was delayed for repairs.

“After passing the second relay station at Grace and North Park Streets, the Duryea wagon ran smoothly along the car tracks at a high rate of speed. At Lawrence Avenue, the operator mistook the direction of the hand on the guide post and went along Clark Street instead of Ashland Avenue. He went two miles out of his way but struck the regular course again by going west on Diversey. But he managed to keep ahead of his rivals.

“A few minutes before 6 P.M., when the Duryea motor came through Douglas Park, laboring over the bad road, there was no one to greet it but a representative of the Times-Herald. On the first approaches to Western Avenue, the roadbed was comparatively hard, and the motor made magnificent time, traveling at the rate of eight mph with ease.

“Not fifty people saw the last stages of the finish or knew that the Duryea had established a world’s record. It was just 7:18 when Frank Duryea threw himself out of the seat of the motor and announced the end.”

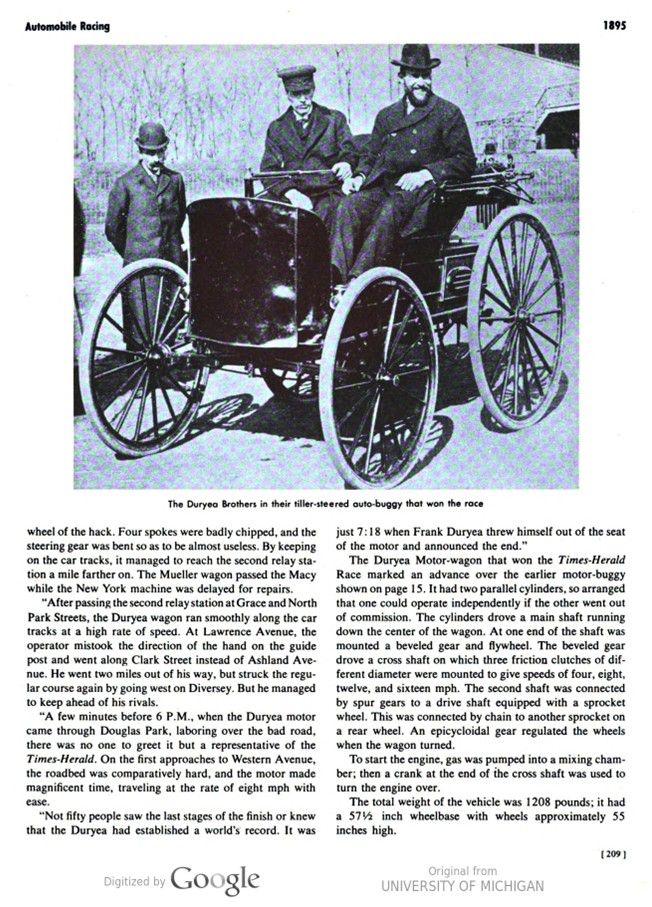

The Duryea Motor-wagon that won the Times-Herald Race marked an advance over the earlier motor-buggy shown on page 15. It had two parallel cylinders, so arranged that one could operate independently if the other went out of commission. The cylinders drove a main shaft running down the center of the wagon. At one end of the shaft was mounted a beveled gear and flywheel. The beveled gear drove a cross shaft on which three friction clutches of different diameter were mounted to give speeds of four, eight, twelve, and sixteen mph. The second shaft was connected by spur gears to a drive shaft equipped with a sprocket wheel. This was connected by chain to another sprocket on a rear wheel. An epicycloidal gear regulated the wheels when the wagon turned.

To start the engine, gas was pumped into a mixing chamber; then a crank at the end of the cross shaft was used to turn the engine over.

The total weight of the vehicle was 1208 pounds; it had a 57½ inch wheelbase with wheels approximately 55 inches high.