Again, Charles Faroux has written reports in La Vie Automobile, on the 1921 French Grand Prix at la Sarthe road course. Briefly, the history of the pre-war race courses from 1904 on till 1914 is described. Then, the coming Grand Prix is described in terms of starting list, the course itself, as well as technical characteristics of some important cars of the race. The report closes with some general considerations and a prognosis.

Text and jpegs with courtesy of the Conservatoire numérique des Arts et Métiers (Cnum) http://cnum.cnam.fr

compiled by motorracinghistory.com and translated by DeepL.com

— LA VIE AUTOMOBILE — Vol. 17. N° 734. July 25 1921

The A.C.F. Grand Prix.

THE MOTORCYCLE GRAND PRIX

When the Automobile Club de France’s Sports Commission decided last year to organize a Grand Prix for 1921, the decision was met with widespread enthusiasm. At that time, it was hoped that a considerable number of entries would be received.

However, the field lining up today to compete for the glorious trophy on the roads of the Le Mans circuit is one of the smallest—if not the smallest—ever seen in an event of this magnitude.

Why?

There are some secondary reasons: overly strict regulations, it has been said… excessive entry fees…; the truth is that the French automotive industry is not doing very well, due to circumstances beyond its control, and that participation in the Grand Prix requires a company that wants to compete regularly to spend several hundred thousand francs.

I said earlier that the original regulations were strict.

Initially, there was talk of putting all competing engines (with a maximum displacement of 3 liters, remember) on the test bench and, in addition to a full-load test, requiring them to meet two performance criteria: at least 30 horsepower at 1,000 rpm and at least 90 horsepower at 3,000 rpm.

These conditions were easily met by all competitors (except Mathis, because he races with a 1,500 cc engine), but that was not where the difficulty lay. The participating manufacturers asked who would test their engines on the test bench.

The Sports Commission, of course, at the A.C.F. laboratory.

However, on the one hand, the Sports Commission includes many manufacturers who do not compete in the Grand Prix, and those who wanted to race told me themselves that they were reluctant to publicly reveal certain details of their engines that they wanted to keep secret, believing that these gave them a certain mechanical advantage.

On the other hand, it was known that the A.C.F. laboratory was poorly equipped, and it was remembered that the 1914 aircraft engine competition had given rise to a huge error, first reported in the columns of La Vie Automobile as soon as the results were published.

As there was resistance, despite the fact that the rules were excellent in themselves and remarkably well thought out, the Sports Commission, eager above all to have the 1921 Grand Prix, acted wisely in deciding that the rules would be the same ones I had set before the war and that I had been fortunate enough to have the Americans adopt in 1920, after a long exchange of letters.

This meant that we could hope to have American competitors at Le Mans, which indeed happened, as the best of them, Duesenberg, crossed the Atlantic.

* * *

Before discussing the history of this great and beautiful classic event that is the A.C.F. Grand Prix, I feel it is necessary to pay public tribute to the Automobile Club de l’Ouest, that powerful group, the most powerful of the regional clubs, which, through its tenacity and initiative, succeeded in securing the Grand Prix.

And yet, what competitors did it have? Strasbourg and Lyon.

Strasbourg presented itself with all the reasons for sentiment that one can imagine. Lyon offered great advantages, and I can still hear myself saying last year to Georges Durand, whose name and actions are inseparable from the history of the A.C.O.:

— You don’t stand a chance. They’ll surely go to Strasbourg, and if something happens in Alsace, Lyon will benefit before you do.“

And I can still hear Durand’s reply: ”Leave it! Leave it alone! I have a better chance than you think.“

And he proved it to us.

All the more reason to congratulate the A.C.O. Moreover, from a purely automotive point of view, no region was better suited than Le Mans, as the Club there has done and continues to do great things, benefiting the entire French industry.

HISTORY OF THE EVENT

When, in 1903, the authorities opposed speed trials on unguarded roads, the idea of racing on a closely monitored circuit had to be adopted. The Gordon Bennett Cup thus became, by force of circumstance, the biggest motor racing event of the year.

However, the rules only allowed each nation, regardless of its industrial importance, to be represented by three cars.

France quickly grew tired of a contest in which it had everything to lose and nothing to gain; it was agreed that each nation should have a chance of winning proportional to its stake.

In 1904

Our victory at Taunus in 1904, in which Théry, driving a Richard-Brasier car, brought the G.-B. Cup back to France, enabled us to make these demands.

The A.C.F. proposed allowing three cars per factory from then on, which would automatically ensure proportional representation.

In 1905

For 1905, the Gordon Bennett Cup rules would remain in place; however, the major foreign clubs undertook to make changes to the Gordon Bennett Cup rules for the following years. However, the Automobile Club de France declared that, regardless of the outcome of the 1905 race, it would organize a major speed event for 1906, in which the principle of factory representation would be adopted.

This generous gesture was rewarded, and Théry’s victory had a worldwide impact.

In 1906

The 1906 Grand Prix was organized under the conditions specified by the A.C.F. Held on the Sarthe circuit over two consecutive days and covering a total distance of 1,228 kilometers, it brought together thirty-four cars representing ten French brands, two Italian brands, and one German brand.

We know how Renault triumphed over a formidable field: Szisz’s fast car covered the entire distance at an average speed of over 101 kilometers per hour. Nazzaro, in a Fiat, was second, a few seconds ahead of the late Albert Clément, who was driving a Clément-Bayard.

The highlight of the day was the appearance in the race of the removable rim created by Michelin.

In 1907

The second A.C.F. Grand Prix was held on the Dieppe circuit. From the start, it was a fierce duel between Duray’s Lorraine-Diétrich and Lancia’s Fiat. After a close battle, Duray took the lead, galloping ahead of the pack, and appeared 150 kilometers from the finish line as the sure winner of the exciting race. We know how the superb steel beast from the Diétrich factories was immobilized by the failure of a ball bearing in the gearbox.

Nazzaro then took the lead, and his Fiat proved to be all the faster as the distance increased. A lightning comeback, but a little too late, by Szisz in his Renault could only bring him within six minutes of the winner, leaving Fiat with a significant advantage.

In 1908

Two races were held in 1908. The Grand Prix for small cars was an opportunity for the manufacturer Delage to claim a fine victory; the unyielding, inexorable regularity of its small car, driven by Guyot, got the better of even the most valiant and formidable opponents. As for Guyot’s average speed, which exceeded 80 kilometers per hour with a simple single-cylinder engine with a bore of 100 and a stroke of 160, i.e., perfectly normal, it caused all the spectators to stare in admiring and sympathetic amazement.

As for the Grand Prix for large cars, for which the four-cylinder engine had to have a uniform bore of 155 millimeters, it was an opportunity for the German clan to achieve a splendid victory. Lautenschlager, in a Mercedes, was the brilliant winner, followed by two Benzes and another Mercedes… The honor of the French flag was saved by the Clément-Bayards, which were undoubtedly the fastest cars in the field, but which were perhaps victims of their own speed, as 175 kilometers per hour seemed excessive for the tires of the time. In a Clément-Bayard, Rigal, who finished first among the French, unofficially broke the lap record with an average speed of over 135 km/h. The tragic death of the excellent Cissac, who was killed while completing his last lap of the circuit, was deeply regretted.

In 1909-1910-1911

For a time, the 1908 Grand Prix seemed to mark the end of major speed trials.

It was a great honor for L’Auto to ensure the continuation of an annual event, despite the resistance encountered; the three races held in Boulogne and the tremendous success of the Grand Prix for light cars sealed the triumph of a cause that was so perfectly just…

In 1912

Very wisely, motorsport officials recognized the need to organize a 1912 Grand Prix by opening it up to two categories of cars: the first had no power or weight restrictions (open formula), while the second had to be equipped with an engine with a displacement not exceeding three liters.

The free formula was only moderately successful, but the Coupe de l’Auto — the title of the three-liter race — was a huge success, attracting forty-four entries.

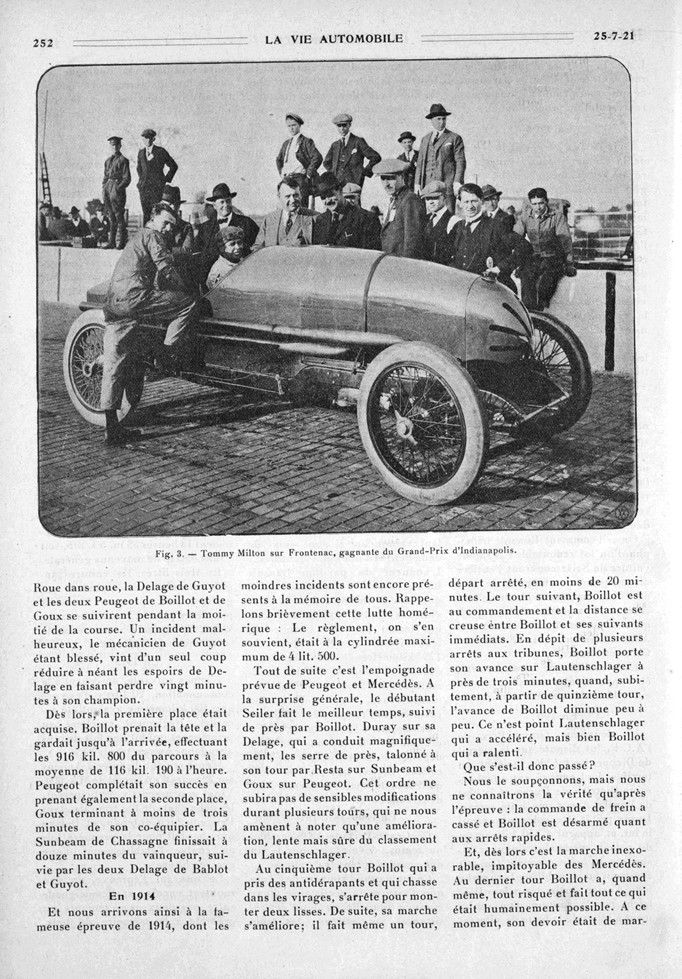

After a thrilling duel between Fiat and Peugeot throughout the first day, the latter brand, with the daring Boillot at the wheel, secured a splendid victory that had a considerable impact on both worlds. Boillot covered 1,540 kilometers of the course in less than 14 hours, exactly 13 hours, 58 minutes, 5.3/5 seconds, at an average speed of over 110 km/h.

In the three-liter class, the English Sunbeam cars triumphed magnificently, taking the top three places: first with Rigal, second with Resta, and third with Médinger.

In 1913

The following year, the race was based on fuel consumption. Twenty liters of gasoline per 100 kilometers had been allowed. An excellent rule in principle, but one that was once again abandoned a little too quickly.

The race was held in Amiens over 29 laps of a 31.6-kilometer circuit. Twenty competitors took part, with the two French leaders being Peugeot, of course, and Delage, which was entering a large car in a race for the first time.

We still remember what the race was like, and the battle between our two representatives is etched in everyone’s memory. Wheel to wheel, Guyot’s Delage and the two Peugeots driven by Boillot and Goux followed each other for half the race. An unfortunate incident, in which Guyot’s mechanic was injured, suddenly dashed Delage’s hopes by causing its champion to lose twenty minutes.

From then on, first place was assured. Boillot took the lead and kept it until the finish, covering the 916 km Peugeot completed its success by also taking second place, with Goux finishing less than three minutes behind his teammate. Chassagne’s Sunbeam finished twelve minutes behind the winner, followed by the two Delages driven by Bablot and Guyot.

In 1914

And so we come to the famous 1914 race, every detail of which is still fresh in everyone’s memory. Let’s briefly recall this epic battle: The rules, as we remember, allowed for a maximum engine capacity of 4.5 liters.

Right from the start, it was the expected battle between Peugeot and Mercedes. To everyone’s surprise, the rookie Seiler set the fastest time, closely followed by Boillot. Duray in his Delage, who drove magnificently, was hot on their heels, followed in turn by Resta in a Sunbeam and Goux in a Peugeot. This order remained largely unchanged for several laps, during which we noted only a slow but steady improvement in Lautenschlager’s position.

On the fifth lap, Boillot, who had taken anti-skid measures and was hunting in the corners, stopped to fit two skid plates. Immediately, his pace improved; he even completed a lap from a standing start in less than 20 minutes. On the next lap, Boillot was in the lead and the gap between him and his immediate rivals was widening. Despite several stops at the stands, Boillot increased his lead over Lautenschlager to nearly three minutes when, suddenly, from the fifteenth lap onwards, Boillot’s lead gradually decreased. It was not Lautenschlager who had accelerated, but Boillot who had slowed down.

What had happened?

We suspect, but will only know the truth after the race: the brake control broke and Boillot was unable to make quick stops.

And from then on, it was the inexorable, relentless march of the Mercedes. On the last lap, Boillot risked everything and did everything humanly possible. At that moment, his duty was to drive at breakneck speed. This brave young man understood that perfectly well, but what had to happen happened, and Boillot experienced the bitterness of having to abandon the race on the last lap.

Let’s say it straight away: in any case, it was a fierce battle between Peugeot and Mercedes. The cars were evenly matched and couldn’t gain much ground on each other over a lap; however, one final observation must be made, in all fairness: Lautenschlager stopped once at the pits, on the tenth lap, to refuel—and stopped for 3 minutes and 15 seconds! Boillot stopped six times in total, with a total stop time of 5 minutes and 49 seconds, but he also had five stops for bandages on the road.

In total, Boillot lost about 20 minutes.

Why?

Boillot, like Goux, had started on anti-skid tires. Both stopped for a few seconds to ask for smooth tires to be prepared for the next lap, but they only had 120s while their competitors had 135s. On these stony, rutted roads, the small tires were a serious handicap.

Perhaps never before, in the history of motor racing, has a defeat been more unfortunate and less deserved than that of Peugeot. Since then, during the war, the two cars have frequently met in America. Peugeot has always won, except once when its driver, Resta, was in the lead on the last lap, rolled over and left Mercedes with the victory.

THE RENAISSANCE OF THE GRAND PRIX

Then came the great turmoil, and until the day after the armistice, our manufacturers devoted themselves exclusively to the war effort.

In 1920, the time seemed premature, but very wisely, the A.C.F. announced the establishment of the 1921 Grand Prix. In the race for circuits, the Automobile Club of Western France came out on top.

In terms of regulations, there was little choice: the Indianapolis rules had to be adopted, and it so happened that, after a long correspondence with the American officials, I had succeeded in 1919 in getting them to adopt the rules that had been in force before the war for the Y Auto light car cup, with a maximum engine capacity of three liters and a minimum weight of 800 kilos.

As soon as the entry list was opened, the French engine specialist Ballot, always combative, entered four cars. Then, at the end of the year, the sports commission received entries for two Talbots, three Talbot-Darracqs, two Sunbeams, one Mathis, and four Duesenbergs. Fiat was also entered but did not start, as it was not ready in time.

The starts

After a draw, the starts were given in the following order:

1. Ballot (de Palma).

2. Sunbeam (Thomas).

3. Mathis (Lamm).

4. Talbot (Seagraves).

5. Talbot-Darracq (André Boillot).

6. Duesenberg (A. Guyot).

7. Ballot (Chassagne).

8. Sunbeam (Lee Guinness).

9. Talbot (Zborowski).

10. Talbot-Darracq (Thomas).

11. Duesenberg (Joë Boyer).

12. Ballot (Wagner).

13. Talbot-Darracq (Dubonnet).

14. Duesenberg (Murphy).

15. Ballot (Goux).

16. Duesenberg (X…).

The start will be given to two cars together, every 30 seconds, starting at 9 a.m.

The course

The Grand Prix course consists of 30 laps of a 17.262-kilometer circuit, for a total distance of 517.860 kilometers.

THE CARS

Ballot. — 8-cylinder in-line engine, 65X112, four valves per cylinder, overhead valve timing:

The car has proven itself; it was the fastest in Indianapolis: the engine power must be 105 to 108 horsepower at around 3,500 rpm, but we can only guess, as the manufacturer has kept all its tests carefully secret.

Ignition is provided by two Scintilla magnetos, a device that greatly impressed me at the last Brussels Motor Show.

Rumor has it that Ballot cars were equipped with a servo brake based on a principle similar to that of Birkigt, but with an external brake shoe instead of an internal band, to control the Perrot front brakes.

Talbot-Darracq-Sunbeam. — The seven cars in the consortium are identical.

Extremely low chassis: front wheels with slight camber; rear wheels in parallel planes.

The engine is also an 8-cylinder 65X112, with two intake valves and two exhaust valves per cylinder, the intake valves having a slightly larger diameter, a smooth crankshaft, the front half offset by 90° from the rear half, as is generally the case.

Aluminum cylinders, steel liners, bronze valve seats. These are features often found on Sunbeam aircraft engines.

The ignition is designed to use either two magnetos or a Delco. Radiator, sheet metal work, and piping by Moreux.

No flywheel on the engine; the counterweights on the balanced crankshaft serve this purpose. Carburetors not yet designated.

The entire car has been carefully designed for resistance to forward motion.

Rear axle consisting of two trumpets drilled from solid metal and joined by an aluminum casing containing the straight bevel gear and differential.

Transmission and torque reaction via short, straight springs. Two Hartford suspensions per wheel. Double cardan shaft—of course—ball cardan on the axle, sliding dice at the rear of the gearbox. Classic 4-speed gearbox. Hele-Shaw clutch. Front axle equipped with an Isotta-Fraschini class brake with direct control.

Duesenberg. — Still a 63.5/118 inline 8-cylinder with Claudel carburetor; it would be both the fastest in terms of angular speed (4,000 rpm) and the most powerful. However, we saw in Indianapolis that the Ballots were faster, which at least for the French chassis indicates better performance at the drive wheel rims.

The Duesenbergs have hydraulically controlled front brakes, which are said to be extraordinarily powerful and effective. Spectators positioned at the various turns of the circuit will have the opportunity to judge for themselves.

The Duesenberg car is full of ingenious details, and we will provide a complete review of it, as it is exceptional for a driver to agree to disclose everything about “racers.”

Mathis. — The friendly Strasbourg-based manufacturer mainly wanted to make a demonstration, as its engine is a simple 4-cylinder 69X100, meaning that Mathis is racing with a displacement of 1.5 liters against 3-liter engines.

Its main features include: directly controlled overhead valves, dual circulation lubrication, twin ignition, and a Solex carburetor.

The clutch is a Mathis multi-disc type and the car has four speeds. Double cardan transmission: as a result, thrust and reactions are provided by springs.

Braking on all four wheels.

GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS

One thing stands out above all else: apart from Mathis, who is primarily aiming for a spectacular commercial demonstration, we see that all competitors have adopted the inline 8-cylinder engine.

Why? Because the main goal is to turn quickly, and it is therefore important to lighten the moving parts.

All competitors have four-wheel braking.

All competitors have adopted overhead valve distribution.

In short, this is the complete and unreserved triumph of all the theories defended for so many years by La Vie Automobile. It is understandable that we feel a legitimate sense of pride.

I would add that all competitors are also fitted with “Straight Side” tires, the type I have opposed. This is a question of safety that takes precedence at 180 km/h, as straight sidewall tires cannot come off the rim, even if they burst. I still believe that tourists should always prefer our European bead-type tires, which are more economical and cause less wear and tear on the car. The future will tell.

For ignition, many competitors use the Delco system, and I believe that such a system is preferable to magneto ignition when it comes to high-speed engines with a large number of cylinders.

Finally, consider that the Le Mans circuit is approximately 17 kilometers long, that 16 cars will be at the starting line, and that the density on the route will therefore be the highest ever seen. Assuming an even distribution, cars will be passing every 30 seconds, taking into account traffic speeds.

This promises to be the most exciting and lively race ever seen in Europe. It may still be too early to make predictions about average speed, but it should be noted that the Le Mans circuit is perhaps not as fast as one might think at first glance; it requires five slowdowns and five starts per lap, three at the top of the triangle and two in the wooded section where there are two consecutive right-angle turns. Under these conditions, even for a car capable of reaching 180 km/h, which is fantastic for a three-liter engine, it seems quite difficult to exceed an overall average of 120 to 125 km/h.

However, I would not be surprised to see some laps completed in less than 8 minutes, 7 minutes 40 or 7.45 for example, which would correspond to an average of around 135 and would be quite remarkable.

A PREDICTION

If everything goes smoothly, I don’t think the Ballots can be beaten, as they are the fastest of the bunch and their state of preparation leaves little room for doubt.

But the distance is singularly too short.

500 km for such machines means, on the one hand, reducing the event to a veritable “sprint” and, on the other hand, placing too much importance on a flat tire or a blowout.

The Sunbeam-Talbot-Darracq team also has some very dangerous cars, and the American threat cannot be ignored, as the Duesenbergs have also proven themselves.

What is certain is that Le Mans is set to host the most exciting Grand Prix ever seen, with the competitors so close to each other.

C. Faroux.

Photos.

Fig. 1. — The Grand Prix circuit.

Fig. 2. — Guyot at the wheel of the Duesenberg.

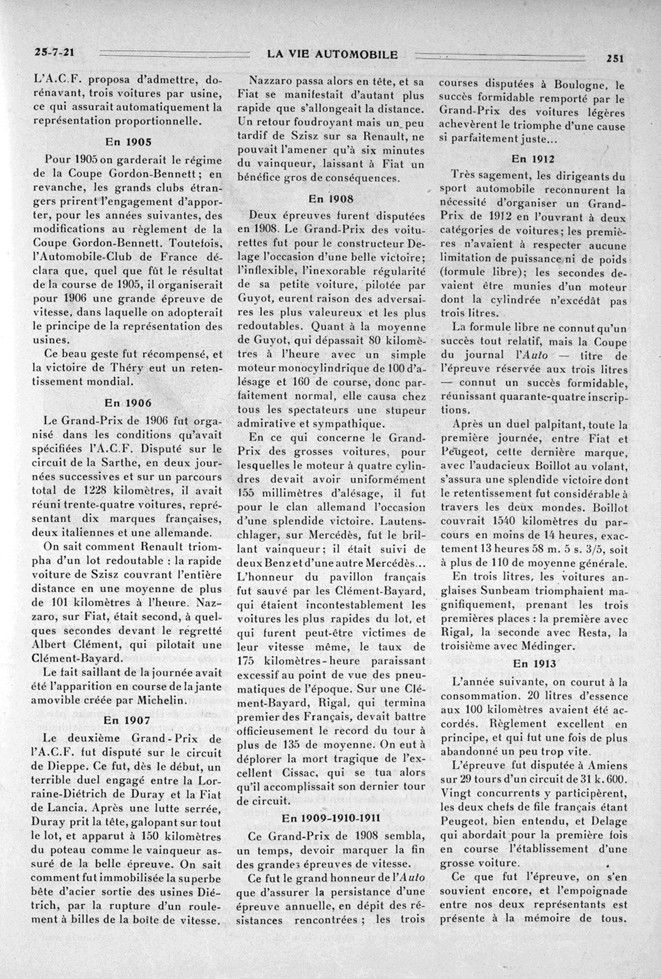

Fig. 3. — Tommy Milton in Frontenac, winner of the Indianapolis Grand Prix.

Fig. 4. — Ralph de Palma at the wheel of the Ballot.

Fig. 5. — Front view of the Talbot-Darracq.

Fig. 6. — The Talbot-Darracq engine.

Fig. 7. — Details of the Talbot-Darracq front brake.