The 1925 Italian Grand Prix was held on the Monza track, that was built only a few years earlier, in 1922. The first two finishers were, again Alfa Romeo, thereby clinching the World championship for manufacturers.

Text and jpegs by courtesy of hathitrust.org www.hathitrust.org, compiled by motorracinghistory.com

MOTOR AGE Vol. XL, No. 7, August 18, 1921

America Shows Old World Its Finest Race

Both Industry and Public in Europe Agree That Murphy’s Winning of the Grand Prix Was Capital Demonstration

By W. F. Bradley (European Correspondent, MOTOR AGE)

LE MANS, France, July 25 – In winning the French 182 cu. in. Grand Prix automobile race, at an average of 78.1 miles an hour, Jimmie Murphy not only established a speed record for long distance road racing in France, but gave the finest demonstration ever seen in the Old World. In the opinion of his rivals and the public alike, the best combination of car and driver won the race.

American prestige has been enormously enhanced by the Duesenberg’s victory in France. The winning was so fair, there was such an absence of the element of chance, that all open-minded spectators admit the best car won.

Boyer’s Duesenberg went out with a broken rod, but Chassagne’s Ballot was eliminated with a broken axle. Jimmy Murphy was overheating when he finished, but this was due to a leaky radiator punctured by a flying stone. Murphy got into his Duesenberg still suffering from his accident of a week before, when, owing to the seizure of the brakes, he overturned in the ditch. He was carrying Louis Inghibert, who had been scheduled to drive No. 4 Duesenberg. Both men were pinned under the car. Inghibert was taken to the hospital with four broken ribs, but although the French doctors declared that Murphy had no fractures, he suffered so much that he believed one rib had been broken. Nevertheless, started in the race well bandaged.

DE PALMA’S CAR SLOWER THAN EXPECTED

All the competition lay between the Duesenberg and the Ballot teams. In addition to these two a couple of Talbots and two French Darracq cars had been entered, also a Mathis of only 91.5 cu. in., or half the piston displacement allowed under the rules. The Talbots and the Darracqs were in an unprepared condition and had been reentered twenty- four hours before the start, after having been withdrawn. The Mathis had been delayed by strikes, and in addition was incapable of winning, by reason of its small piston displacement.

Louis Wagner burned the fabric lining of the Ballot clutch on the initial lap and after losing a quarter of an hour in making repairs, and being further delayed by sticking throttles, he did not figure as a serious contestant. Ralph De Palma, looked upon by the public as the fastest of the Ballot quartette, did not seem to have the speed that was expected of him, and admitted after the race that his car was five miles an hour slower than when he drove it in America. He also was delayed by sticking throttle barrels. This defect was overcome by fitting extra springs, but not until a certain amount of time had been lost on the turns.

Owing to the accident to Louis Inghibert, the fourth Duesenberg had been given to Andre Dubonnet, a French millionaire amateur who had figured in local events but never previously taken part in an international speed contest. He proved himself a good driver, but rather weak on pit work.

After a couple of laps Jean Chassagne proved that he was the fastest of the Frenchmen. He handled his Ballot in a wonderfully clever manner, and after trailing Murphy and Boyer for six laps he got ahead of the Detroiter in the seventh and took the lead on the twelfth lap after Murphy had stopped for two rear tires and gas. The Frenchman held the leading position for the next six laps, but could not shake off either Murphy or Boyer and began to be threatened by Albert Guyot, who, after an indifferent start, began to climb rapidly.

The height of excitement was reached at this point, for it was evident that all the French hopes rested on Chassagne. De Palma had never been able to get better than fourth, Goux was handicapped by having a car with a piston displacement of only 122 cu. in., and Wagner had a lot of time to make up by reason of his clutch trouble at the start.

While Boyer and Murphy were chasing Chassagne hard, the difference between the blue French and the white American cars always being less than a minute, Chassagne pulled into the pits with gasoline streaming from his tank. It was given out that a flying stone – the course was thickly strewn with them – had gone through the tank. The real cause was the opening of the real axle when the Ballot skidded on one of the turns in an effort to avoid Dubonnet’s Duesenberg. The fractured axle struck the gas tank. This accident was similar to the one which befell Thomas when driving in the Targa Florio race.

MURPHY DISREGARDS „GO SLOW“ ORDERS

With Chassagne out, Jimmie Murphy had the race in his hands, and was never headed until he crossed the line a winner. His victory seemed so sure that George H. Robertson, who was managing the team, hung out the „go slow“ sign, which Murphy admitted afterwards he had ignored.

For ten consecutive laps, or until the end of the 27th, the position was Murphy first, Guyot second, with De Palma on the Ballot running third. On the 28th lap Guyot had to stop to change tires and dropped into third place, De Palma going into second place a little more than 18 minutes behind Murphy’s Duesenberg. The mechanician, who had worked hard changing tires, who had been hit on the head by flying stones, and had had all the skin taken off his nose by burning rubber, was unable to crank the engine. Arthur Duray, watching the race as a spectator, vaulted the railings, hat- less, and in black clothes, and took the place of the exhausted man. Two laps were made in this way, but the clutch trouble pulled Guyot down from second to sixth place in these 21 miles. These incidents made De Palma sure of second place, and enabled Goux, with his 122 cu. in. four-cylinder Ballot to work into third place. Dubonnet got fourth.

The race was started at one minute intervals, and in pairs. There were only thirteen competitors, but as the course measured 10.7 miles round, there never was a dull moment at the grandstands. Tires played an important role, but did not falsify the results.

STRAIGHT SIDE TIRES MAKE SHOWING

This race had done more to help the straight side than a year’s ordinary newspaper propaganda. The French motoring public attaches an immense amount of importance to the lessons learned in racing, and the theorist who now comes forth to prove the detrimental influence of circumferential weight is likely to receive scant attention. There are no signs that anybody is preparing to profit by this demonstration, but the fact remains that this race has made the way easier for the intro- duction of the straight side tire by dissipating many of the prejudices which existed against it.

AMERICAN CARS LIGHTER THAN EUROPEAN RIVALS

The French cars had decidedly better tires for this class of road, and were handicapped over such a comparatively short distance as 322 miles. Had the test been for 500 miles the better European tires might have decided the race in favor of the Ballots.

A very favorable impression was created by the low weight of the Duesenberg cars, compared with the European machines, and the conclusion was drawn that American metallurgists have got ahead of their European rivals.

Ignition honors were equally divided. Delco equipped Duesenberg, Talbot and Darracq, and the Swiss Scintilla magneto was used on the Ballot cars. There was no ignition troubles, and plugs, which were K. L. G.’s for the Europeans and A. C.’s for the Americans, were equally satisfactory.

After arrival in France, three of the Duesenberg cars were equipped with the French Claudel carbureter. Murphy decided to retain his Miller, which he had got into first class condition, for although the Claudel seemed to be rather better on acceleration, he was not disposed to take the risk of a road accident during a final test on the day before the race. The trouble with the Claudels was sticking throttle barrels, occasioned by road dust. Chassagne foresaw this and fitted a very heavy recall spring. Wagner and De Palma had to fit extra springs during the race. This was not the fault of the drivers so much as of the firm, for Ballot did not encourage suggestions from his drivers, and Chassagne was in a position to get work done which could not be attempted by the others.

SEIZE DUESENBERG CARS FOR INFRINGEMENT OF PATENT

Paris, July 28 – Claiming an infringement of their patents on hydraulic four-wheel brake systems, the Rolland-Pilain Co., of Tours, made a descriptive seizure of one of the Duesenberg cars at Le Mans today. This action was taken, declared the Rolland-Pilain Co., in order to protect their legal rights in this system of braking. The seizure was merely of a technical character and does not tie up the cars or interfere with any of the arrangements made for shipping them back to America. Rolland-Pilain exhibited a hydraulic braking system at the Paris show in 1910, and although never having been in production, intends to put his brakes on the market next year. The Duesenberg brakes are built under license obtained from an American company.

Photo captions.

Page 10.

Albert Guyot, left, who drove a Duesenberg in the French Grand Prix. Georges Carpentier was there with his winsome smile.

Page 11.

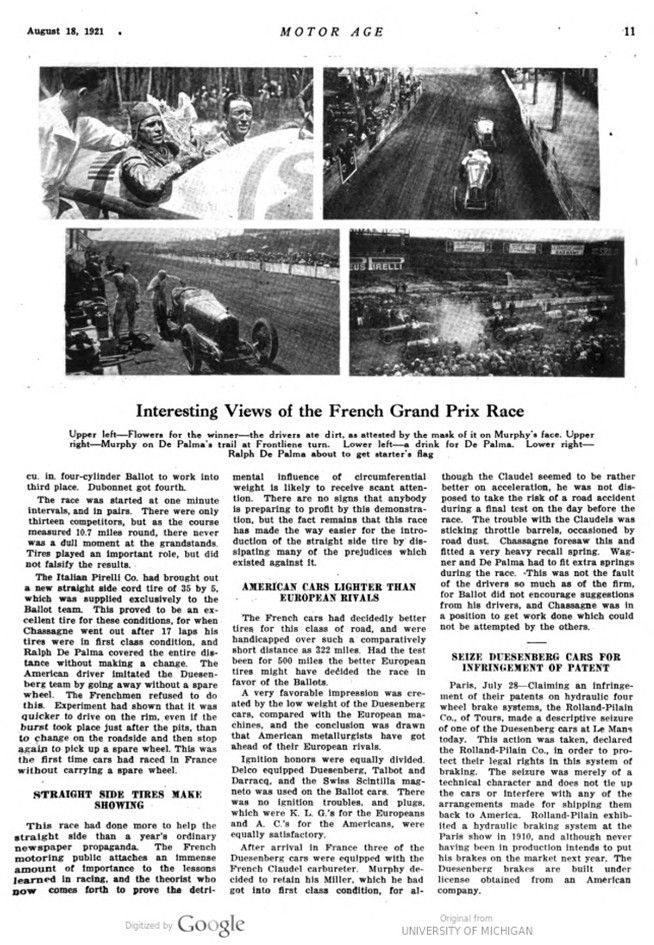

Interesting Views of the French Grand Prix Race

Upper left – Flowers for the winner – the drivers ate dirt, as attested by the mask of it on Murphy’s face. Upper right-Murphy on De Palma’s trail at Frontliene turn.

Lower left – a drink for De Palma. Lower right – Ralph De Palma about to get starter’s flag