Text and photos by authorisation of Bibliothèque nationale de France- gallica.bnf.fr https://www.bnf.fr/fr

Translation by DeepL.com of Le Grand Prix de l’ACF

La Vie au Grand Air, 9th Year, No. 405, 23 June 1905, page 464-469

THE GRAND PRIX OF THE A. C. F. – By C. FAROUX

Final farewell to the Gordon Bennett Cup.

This year’s event is fairer, because it ensures that each country is represented in automatic proportion to its production power.

On the choice of racing circuits and their influence on car construction.

A few edifying comparisons

To the Gordon-Bennett Cup, which for six years had been the supreme goal to which the manufacturers‘ entire effort was directed, starting from 1906, was succeeded by the Grand Prix de l’Automobile-Club de France. The beautiful trophy donated by James Gordon-Bennett has, due to circumstances, had a magnificent destiny that no one otherwise could have foreseen: here it is today, relegated to the rank of museum object.

As for the last three years, the great race of 1906 race will be run on a circuit to be rounded in a given number of times in this case, the Circuit de la Sarthe, a little over a hundred kilometers in length, to be rounded twelve times over two consecutive days. But, in profound difference to the rules of the Gordon Bennett Cup, the Grand Prix regulations granted to each factory, rather than each nation, the right to enter three cars.

Origin of the Circuit

It is interesting to wonder how, for the major motor racing events, it came about that the city-to-city race, however attractive these are, was replaced by the race on a circuit. Many believe that it was caused by the terrible accidents that marked the first stage of the Paris-Madrid race. Undoubtedly, this bad day had a certain influence on subsequent decisions, but it is important to point out that, even before Paris-Madrid, the English, who at that time held the Gordon Bennett Cup, had decided to run the Irish race on a circuit, and because it was absolutely impossible to find a road in the entire United Kingdom, that would allow a city-to-city race.

Certainly, the English did not have the first idea, since the Belgians had already run their first Circuit des Ardennes in 1902: the first winner, Charlie Jarrott, moreover, made himself the apostle of the new system to the directors of the Automobile-Club of Great Britain.

What’s more, the Circuit of Ireland offered many new features compared to the Belgian Ardennes. The former, in fact, because it passed through relatively important urban areas, required a completely new organisation in many respects. Besides it was marvellous. The following year, the Cup would be run in Germany, the French manufacturers had their qualifying rounds run on the Circuit des Ardennes in France. Théry, driving a Brasier, gained first place, paving the way for his resounding victory the following month.

In 1905, the Cup was run in France. The Circuit de l’Auvergne was chosen, difficult and hilly. Théry and his unbeatable Brasier car triumphed again in the qualifications, as in the final round.

In 1905, just as in 1904, we could see that the leaders of motor sport were keen to have the major events run on difficult circuits: I would say circuits with plenty of bends, in ramps and descents. The reasons which seem to have inspired this choice, for instance in Auvergne, are many.

Choosing a racetrack

First of all, a very hilly circuit, that requires fast stops and starts, repeated changes of gear, puts the clutch, the brakes and the gearbox gears to the test: so, it is acceptable that by choosing a layout that puts these various components to work, and very hard, it was intended to exert a positive influence on the construction. This is a consideration has its weight. On the other hand, the vision of the monsters that run on American tracks and which bear only a distant resemblance to a motor car worth of bearing the name, may have frightened those who set the course for the major events.

All in all, these reasons have their merits, which I don’t think to question: I only wonder whether, by examining the question from another aspect, we wouldn’t be led to exactly the opposite conclusions. In all branches of sport, pure speed is the criterium of maximum value, and the sprinter is always considered superior to the stayer. This is, moreover, a fact of experience. The lot that competes in the Derby is better than the lot that lines up in the Gladiator. Zimmerman was of a higher quality than Huret, and Orton or Duffy are intrinsically better than Len, Hurst or Ragueneau. Mechanics are no different.

So, you can see what I’m getting at. It is certain that if a car gave 600 kilometers from start to finish, the engine would be subjected to a test of incomparable level. It is not built to withstand unpunished – or at least we are not sure – piston speeds that could attain up to 8 meters per second, exhaust pressures of 4 or 5 kilos, etc…

Under these conditions, the really hard circuit is the smooth and easy one, with a long, non-stop course and without those dangerous bends, without treacherous surprises that await the driver on the roads of the Auvergne. We must, as far as possible, reduce the importance of the driver.

Tricot, wrote Mr. Paul Hamelle in a happy formulation, could have beaten Zimmerman on a round table, and Flying Fox, racing in Colombes against salesmen, would not have been certain of victory. Large-scale slaughter, like the great mechanisms, can scarcely cope with courses on which they cannot freely develop their power.

For all these reasons, we would applaud without hesitation the choice made by the Circuit de la Sarthe Sports Commission for 1906.

Influence of the circuit on the construction

In Auvergne, where there were many bends, it was quite natural to make the cars relatively low and to move the center of gravity backwards with the dual aim of ensuring maximum grip for the driving wheels and clearing the front wheels to reduce tire wear.

It turns out that lowering the center of gravity has been universally recognized as an excellent arrangement: the reduction in the car’s sway leads to less tire and chassis component wear. This is why, even though the Circuit de la Sarthe only has long straights, we will see fairly low cars again this year.

Power has increased a little compared with last year, but without exaggeration: after all, in most cases, three gears have been sufficient.

For 1906, there are about as many supporters of chain drive as there are of cardan shafts: however, we have all noticed that at high speeds, a chain-driven car is much easier to handle and “holds” the road better than a cardan shaft car. Add to this the fact that the first mode of transmission causes much less wear to the drive wheel tires, and you will be led, for cars of equal quality, to give a certain preference to chain drive cars.

Some comparisons

Since we are on the subject of this fascinating question of racing circuits, we are naturally led to compare the most recent of them.

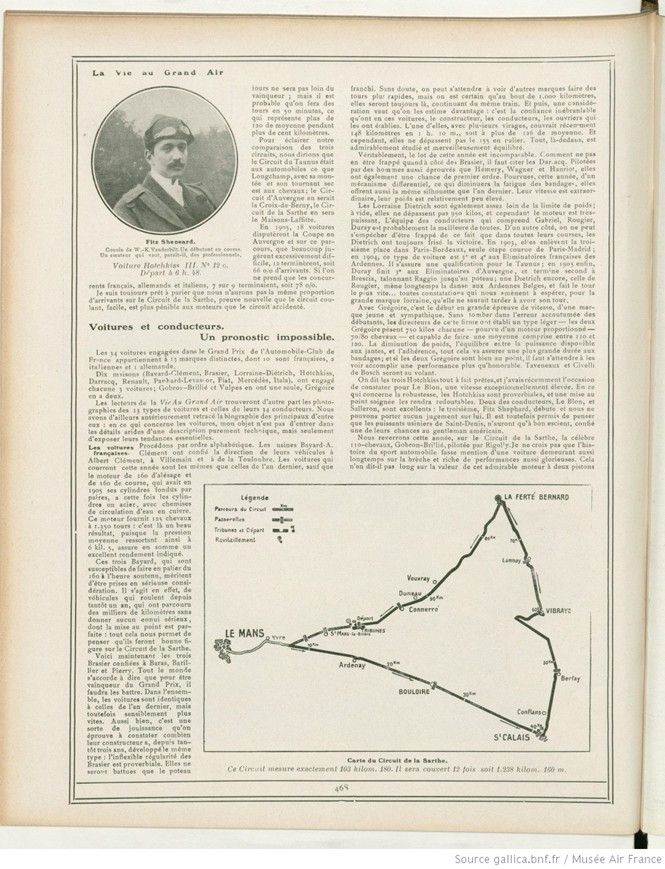

We will take, if you don’t mind, the Taunus Circuit, the Auvergne Circuit and the Circuit de la Sarthe. Their individual developments are quite comparable, but their natures are essentially different.

To compare them, we will take into account the ramps and bends, counting as a bend any curve with a radius of less than fifty meters which, when encountered in the momentum, requires a significant slowing down followed by starting at an intermediate speed.

The Circuit du Taunus had 31 bends per lap, none of which were really difficult, but half a dozen of which required a maximum speed of 45 km/h, a few fairly steep ramps and two or three steep slopes, in the famous Liembourg descent.

The winner, Théry, averaged 96 kilometers per hour.

Last year, the Circuit d’Auvergne had 214 bends per 137-kilometer lap; the ramps were numerous and steep and nowhere did the drivers encounter a 4-kilometer straight: Théry, once again the winner, did about 78.5 kilometers per hour on Brasier.

For 1906, the Circuit de la Sarthe has only 12 turns per lap and is full of straights. There are few sensitive ramps, and it is likely that they will only have to leave the high speed to attack the hill that begins at the exit of Connerré. What average speed will they achieve there? With the old regulations, we would probably have reached 120, but, given that all refueling and repairs must be done by the means on board, I believe that the man who averages 100 over the two days will not be far from the winner; but it is likely that we will do laps in 50 minutes, which represents an average of more than 120 for more than a hundred kilometers.

To clarify our comparison of the three circuits, we would say that the Circuit of Taunus was to cars what Longchamp, with its climb and tight corner, is to horses; the Circuit of Auvergne would be the Croix-de-Berny, the Circuit of Sarthe would be the Maisons-Laffitte.

In 1905, 18 cars competed for the Cup in Auvergne and on this course, which many considered excessively difficult, 12 finished, or 66% of those arriving. If we take only the French, German and Italian competitors, 7 out of 9 finished, or 78%.

I am still willing to bet that we will not have the same proportion of newcomers on the Circuit de la Sarthe, further proof that the flowing, easy circuit is more strenuous for engines than the bumpy circuit.

Cars and drivers. An impossible prediction.

The 34 cars entered in the Automobile-Club de France Grand Prix belong to 13 different makes, of which 10 are French, 2 Italian and 1 German.

Ten manufacturers (Bavard-Clément, Brasier, Lorraine-Diétrich, Hotchkiss, Darracq, Renault, Panhard-Levassor, Fiat, Mercedes, Itala) have entered three cars each; Gobron-Brillié and Vulpes have only one, Grégoire has two.

Readers of Vie Au Grand Air will also find photographs of the 13 types of cars and their 34 drivers. We have also previously traced the biographies of the main ones: as far as the cars are concerned, my aim is not to go into the dry details of a purely technical description, but only to explain their main features.

The French cars.

Let’s proceed in alphabetical order. The Bayard-A. Clément factories have entrusted the management of their vehicles to Albert Clément, in Villemain et a de la Touloubre. The cars that will be racing this year are the same as last year’s, except that the 160-bore and 160-stroke engine, which in 1905 had its cylinders cast in pairs, this time has steel cylinders with copper water-cooling jackets. This engine provides 125 horsepower at 1,350 revolutions: this is a good result, since the average pressure thus emerging at 6.5 kil. 5, in short, ensures excellent indicated output.

These three Bayards, which are capable of sustained speeds of 160 km/h, deserve serious consideration. They are vehicles that have been on the road for a year now, have covered thousands of kilometers without any serious problems, and are perfectly tuned: all of which leads us to believe that they will do well on the Circuit de la Sarthe.

Now here are the three Brasiers entrusted to Baras, Barillier and Pierry. Everyone agrees that to win the Grand Prix, they will have to beat them. On the whole, the cars are identical to last year’s, but significantly faster. It is also a kind of pleasure to see how much their manufacturer has developed the same type over the past three years: the unyielding consistency of the Brasier is proverbial. They will only be beaten once the finishing line is crossed. No doubt we can expect to see other makes doing faster laps, but we are certain that after 1,000 kilometers they will still be there, continuing at the same pace. And then there is one consideration that makes us value them more highly: it is the unshakeable confidence that the manufacturer, the drivers and the workers who built them have in these cars. One of them, with several bends, recently covered 148 kilometers in 1 hour and 10 minutes, which is an average of over 126. And yet, they do not exceed 155 in a rally. Everything in them is admirably designed and wonderfully balanced.

This year’s lot is truly incomparable. How can one fail to be struck by the fact that, alongside the Brasier, the Darracqs must be mentioned. Driven by men as experienced as Hémery, Wagner and Hanriot, they also have a first-rate chance. This year, they are equipped with a differential mechanism, which will reduce tire wear, and they also have the same silhouette as last year. Their speed is extraordinary, and their weight is relatively low.

The Lorraine Dietrichs are also quite far from the weight limit; unladen, they do not exceed 950 kilos, and yet the engine is very powerful. The team of drivers includes Gabriel, Rougier, Duray and is probably the best of all. On the other hand, one cannot help but be struck by the fact that in all their races, the Dietrichs have always come close to victory. In 1903, they took third place in Paris-Bordeaux, the only stage run from Paris to Madrid; in 1904, this type of car was 3rd and 46th in the French Ardennes Eliminations. It secured a qualification for the Taunus; finally, in 1905, Duray finished 38th in the Auvergne Eliminatoires, and finished second in Brescia, tailing Raggio until the finish line; another Dietrich, Rougier’s, led the dance for a long time in the Belgian Ardennes, and made the fastest lap … all observations that lead us to hope that it won’t be long before the great Lorraine brand has its turn.

With Grégoire, it’s the beginning of a great speed event for a young and friendly brand. Without making the usual beginner’s mistakes, the directors of this firm have created a lightweight model—the two Grégoires weigh 750 kilos each—with a proportionate engine—70/80 horsepower—capable of reaching an average speed of between 110 and 120. The reduction in weight, the balance between the power available at the rims and the grip, all this will ensure a longer life for the tires; and if the two Grégoires are well tuned, we can expect to see them achieve a more than honorable performance. Taveneaux and Civelli de Bosch will be at the wheel.

The three Hotchkiss are said to be completely ready, and I recently had the opportunity to observe an exceptionally high speed for Le Blon. As for robustness, the Hotchkiss are proverbial, and careful tuning will make them formidable. Two of the drivers, Le Blon and Salleron, are excellent: the third, Fitz Shephard, is a beginner and we cannot make any judgment about him. However, it is reasonable to think that the powerful manufacturers of Saint-Denis will have wisely entrusted one of their chances to the American gentleman.

This year, on the Circuit de la Sarthe, we will see the famous 110-horsepower Gobron-Brillé, driven by Rigolly. I don’t believe that the history of motor racing mentions a car that has been so long in the breach and with such glorious performances. This says a lot about the value of this admirable engine with two pistons in the same cylinder, which is the best balanced I know. This Gobron car is about to start its fourth racing season. It is commonly thought, thinking only of its famous kilometer records, that the Gobron will not last the distance. What a mistake! In 1904, Rigoly only lost the Ardennes circuit because of his tires; in 1905, he finished seventh in the Auvergne Eliminatory, despite an hour-long stop caused by a magneto failure and after a very cautious race. Moreover, the long wheelbase of the Gobron – 3 meters – meant that it took slower corners, and this was a significant handicap on a circuit as bumpy as the one in Auvergne. This disadvantage became an advantage on the Sarthe, and I would be very surprised if the Gobron did not have an admirable race there.

Finally, here are the three dreaded Panhard cars, driven by Heath, Teste and Tart. Like their older sisters, they have a bevel gear transmission, and their engine is probably one of the most powerful. That they will last the distance is beyond doubt, and if, on the morning of the second day, some of them have difficulty getting going again, it is almost certain that a turn of the crank will be enough to start the Panhard engines. These cars do a good 160 km/h on level ground; they will travel at the same speed from start to finish, and if the tires are kind to them, they will be there at the finish line. I could not praise the Panhard more highly than to quote one of the most notorious competitors: “If the race were 12,000 kilometers instead of 1,200, there would be no one to beat the Panhard.”

The penultimate French brand is Renault Frères, whose successes in major events are countless. The manufacturer has preserved for the “racers” the general appearance of the touring cars of the celebrated factory, and if you saw Scisz or Edmond or Rich z driving by in idle, you would think he was driving an honest 35 horsepower.

But in truth, these 100-horsepower Renaults have lightning speed and their takeoff is astonishingly sudden: well, no doubt can be cast on the finish of their construction.

Vulpes closes the French lot; it is also a newcomer. The vehicle will be entrusted to an excellent driver: Barriaux. It reveals ingenious features: in particular a lowered chassis – 1 cent Stabilia – which is certainly an advantage for driving in a straight line: the tires are simultaneously less fatigued. We can expect good speeds from Vulpes.

The foreigners

In the presence of the national lot, we find 3 Mercedes, 3 Fiats, 3 Italas.

The German cars are the same as last year’s, but improved in many details. Their manufacturers think they will be more successful than last year. I consider them to be very good cars that it would be wrong to judge too hastily. The drivers are Jenatzy, Mariaux and Florio: the first is justly renowned, the second has not yet been able to show us what he can do, but Chailey is held in high esteem, it seems.

Lancia, Nazzri and Weillschott will be at the wheel of the Fiats. The first two make a wonderful team. The cars of the great Italian marque will arrive at the Circuit preceded by a flattering reputation and will be keen to confirm their superb performances of 1905: they must be seen as very formidable competitors.

The young Itala brand made a debut that everyone still remembers. The cars are equipped with a marvelous engine and will in no way detract from the foreign team, entrusted to di primo cartello drivers Cagno, Baron de Caters, Fabry, they are well qualified to represent Italian industry.

Overview

If we take a look at all the cars, we will see that they all tend, or almost all tend towards an identical type. The external appearance, the engine specifications, the life figures, the size, etc., differ little from one another. Out of 13 makes, 6 have chain transmission, 7 have cardan transmission, and all of them naturally have a magneto, but the ignition is different. Thus, out of 34 cars, 26 are equipped with a Simms-Bosch magneto, of which 19 with breakers and 7 with spark plugs. The Grouvelle and Arquembourg finned radiator is found on 20 cars, 3 of which (the Darracqs) have adopted the finned shape. All the cars have wooden wheels with artillery hubs, except the Darracqs, Hotchkiss, Renaults and Vulpes, which have metal wheels.

Who will win? A question to which it is materially impossible to provide an answer. However, I do not believe that victory will escape a French make.

C. FAROUX.

In our next issue, which will appear on June 30, we will publish a report of the A. C. F. Grand Prix, illustrated by the snapshots of our ten photographers spread out along the Circuit course.

Photo captions.

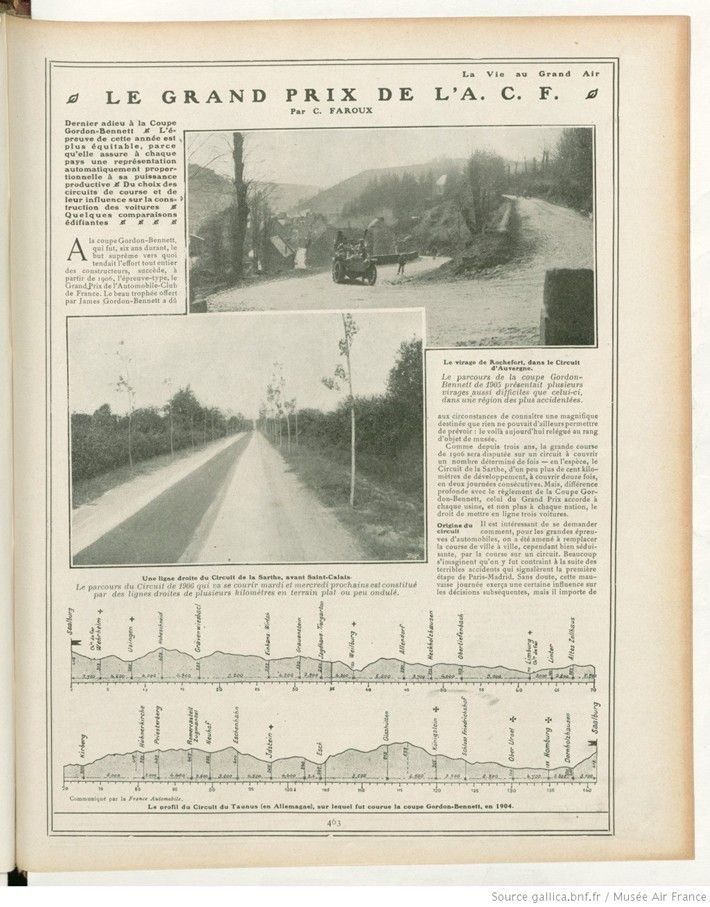

A straight line of the Circuit de la Sarthe, before Saint-Calais.

The 1906 Circuit course, which will be raced on Tuesday and Wednesday, consists of several kilometers of flat or slightly undulating straights.

The Rochefort corner, on the Circuit d’Auvergne.

The 1905 Gordon Bennett Cup course featured several corners as difficult as this one, in a very rugged region.

Press release from France Automobile.

The profile of the Circuit du Taunus (in Germany), where the Gordon Bennett Cup was held in 1904.

Press release from France Automobile.

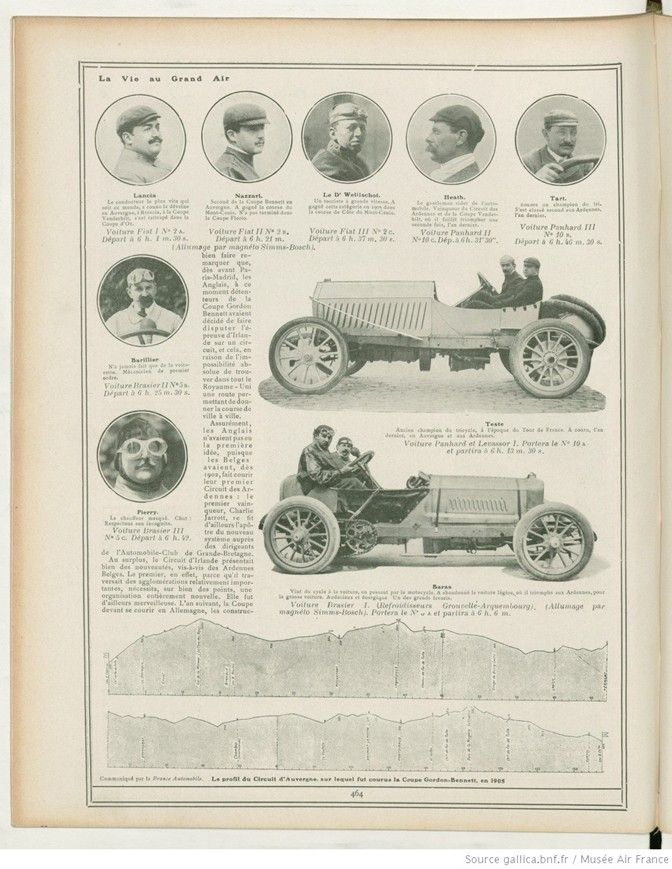

The profile of the Circuit d’Auvergne, where the Gordon Bennett Cup was held in 1905.

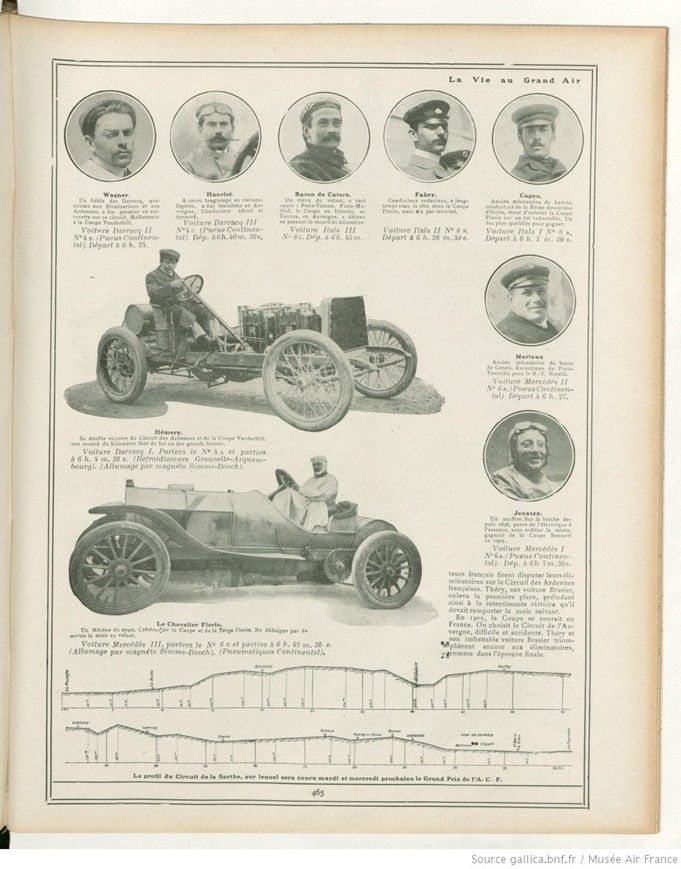

The profile of the Circuit de la Sarthe, where the A. C. F. Grand Prix will be held next Tuesday and Wednesday.

Map of the Circuit de la Sarthe. This circuit measures exactly 103.180 kilometers. It will be covered 12 times, or 1,238 kilometers. 160 meters.

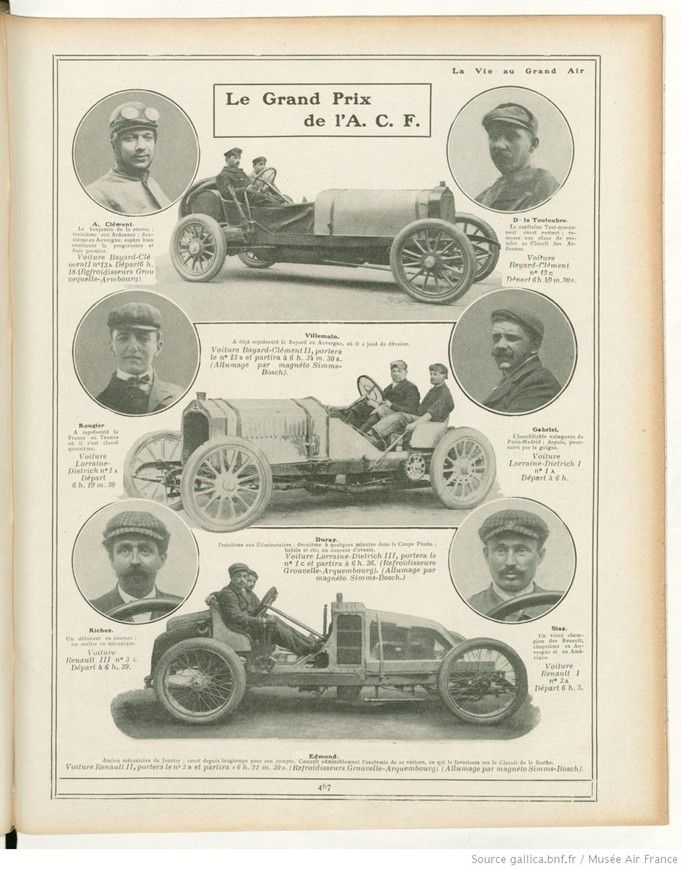

Lancia. The fastest driver in the world, had bad luck in Auvergne, in Brescia, in the Vanderbilt Cup, made up for it in the Gold Cup. Car Fiat I No. 2 A. – Start at 6 hours 1 minute 30 seconds.

Nazzaro. Second in the Bennett Cup in Auvergne. Won the Mont-Cenis race. Did not finish in the Florio Cup. Fiat 77 car – NO 2 B. – Start at 6:21 a.m.

Dr. Weillschot. A high-speed tourist. Won this category in 1905 in the Mont-Cenis Hillclimb. Fiat III Car No. 2 c. – Start at 6:37:30.

Heath. The gentleman automobile rider. Winner of the Circuit des Ardennes and the Vanderbilt Cup, where he almost triumphed a second time last year. Car Panhard II – N, 10 c. Start at 6:31:30.

Tart. Another three-time champion. Finished second in the Ardennes last year. Car Panhard III No. 10 B. – Start at 6:46:30 a.m.

Barillier. Has only ever driven a small car. First-rate mechanic.

Car Brasier UN” 5 B. – Start at 6:25:30 a.m.

Pierry. The masked driver. Shh! Let’s respect his incognito. Car Brasier III – No. 5 c. – Start at 6:42 a.m. (Ignition by Simms-Bosch magneto).

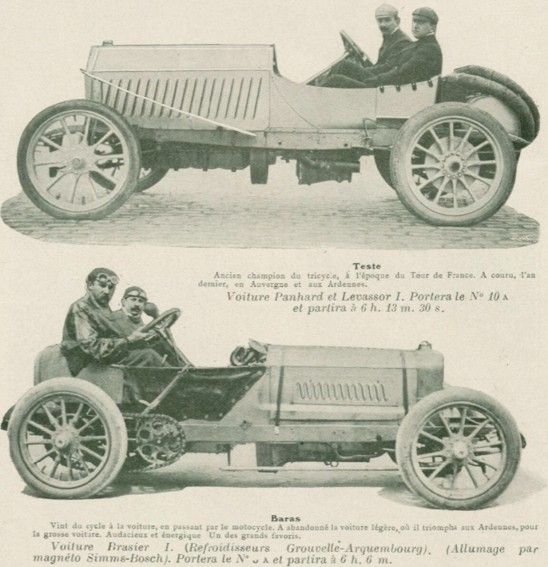

Teste. Former tricycle champion, in the days of the Tour de France. Last year he raced in Auvergne and the Ardennes. Car Panhard et Levassor I. Will carry the number 10 A and will leave at 6:13:30 a.m.

Baras. Moved from cycle to car, via motorbike. He abandoned the light car, in which he triumphed in the Ardennes, for the big car. Bold and energetic One of the big favorites. Car Brasier I. (Refroidisse Grouvelle-Arquembourg) (Magneto ignition Simms-Bosch), will carry the N° 3A and will start at 6 h. 6 m.

Wagner. A Darracq regular, fourth in the Eliminations and the Ardennes, finished first in the buggy on this circuit. Unlucky in the Vanderbilt Cup. Darracq II Car No. 4 B. (Continental tires). – Start time 6:24 a.m.

Hanriot. Ran for a long time in light cars, finished third in Auvergne. Skilled and proven driver. Car Darracq III N,4 c. (Continental tires). – Dep. at 6:40:30 a.m.

Baron de Caters. An old hand at the wheel, has raced everything: Paris-Vienna, Paris-Madrid, the Cup in Ireland, Taunus, Auvergne, has held the kilometer record in passing. Car: Itala III No. 8 c. – Departs at 6:45 am.

Fabry. A daring driver, held the lead for a long time in the Florio Cup, but did not finish. Car: Itala II No. 8 B. – Departs at 6:28 a.m. 30 s.

Cagno. Former Lancia mechanic, driver of the Dowager Queen of Italy, has just won the Florio Cup against formidable opposition. One of the most likely to win. Car Itala I No. 8 A. – Start at 6 hours 1 minute 30 seconds.

Mariaux. Former mechanic of Baron de Caters. Record holder of Paris-Trouville for the N.-Y. Herald. Car Mercedes 11 No. 6 A. (Continental tires) Start at 6 hours 27 minutes.

Jenatzy. An ancestor. On the scene since 1898, he went from electric to gasoline, not forgetting the mixed, winner of the Bennett Cup in 1903. Car Mercedes I No. 6a. (Continental tires). Dep. at 6h 7m,30s.

Hémery. His double victory in the Circuit des Ardennes and the Vanderbilt Cup, and his kilometer record make him one of the favorites. Car Darracq I. Will carry the number 4 A and will start at 6:04:30 (Grouvelle-Arquembourg radiators). (Simms-Bosch magneto ignition).

The Chevalier Florio. A patron of sport. Creator of the Coupe and the Targa Florio. Not above putting his hand to the wheel. Mercedes III car, will carry the number 6 C and will leave at 6 hours 42 minutes 36 seconds. (Ignition by Simms-Bosch magneto). (Continental tires).

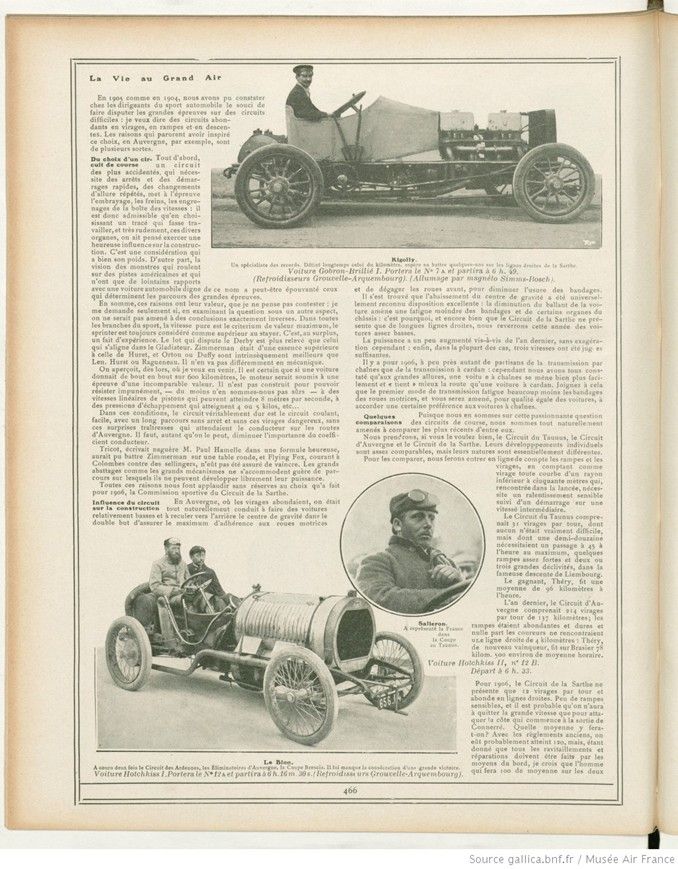

Rigolly. A specialist in records. Held the kilometer record for a long time, hopes to beat a few on the straight lines of the Sarthe. Gobron-Brillié I car. Will carry the number 7 A and will start at 6:49. (Grouvelle-Arquembourg coolers). (Ignition by Simms-Bosch magneto).

Salleron. Represented France in the Taunus Cup. Hotchkiss II car, No. 12 B. Start at 6:33 a.m.

Le Blon. Raced twice on the Circuit des Ardennes, the Auvergne Eliminatory, the Brescia Cup. He has yet to achieve a major victory. Car Hotchkiss I. Will bear the NI, I?, K and will leave at 6 h.16 m. 30s. (Grouvelle-Arquembourg radiators).

A. Clément. The youngest of the race, third in the Ardennes, second in Auvergne; hopes to continue the progress and finish first. Car Bayard-Clément No. 13A Start 6:18 a.m. (Refroidisseurs Grouvelle-Arquem bourq).

De la Touloubre. Captain Tant-que-ça-peut races everywhere; regains a place as first at the Circuit des Ardennes. Car Bayard- No. 13 c Start 6h. 49 m. 30s.

Villemain. Has already represented Bayard in Auvergne, where he was unlucky. Bayard-Clément car He will carry the number 13 B and will leave at 6 h 34 m 30 s. (Ignition by Simms-Bosch magneto).

Rougier. Represented France in Taunus where he came fourth. Voilure I.orraine-Dietrich No. 1 A – Start 6:19:30 a.m.

Gabriel. The unforgettable winner of the Paris-Madrid race, ever since pursued by misfortune. Lorraine-Dietrich I No. 1 A – Start at 6 a.m. Car Renault II, will carry the n° 3 B and will leave at 16 h. 22 m. 30 s. (Grouvelle-Arquembourg radiators) (Simms-Bosch magneto ignition).

Duray. Third in the Eliminatories, second a few minutes later in the Florio Cup, skilful and safe, a driver with a future. Lorraine-Dietrich III car, will carry the n9 1 c and will start at 6:36. (Coolers Grouvelle-Arquembourg), (Simms-Bosch magneto ignition.).

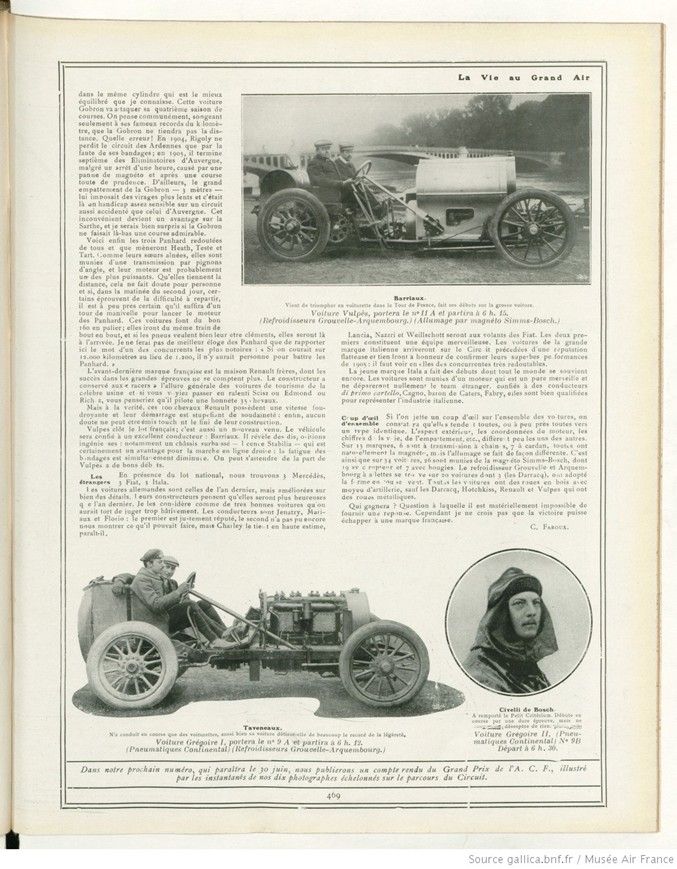

Richez. A racing novice and a master mechanic. Renault III car n° 3 c – Start at 6:39.

Sisz. An old Renault champion, fifth in Auvergne and in America. Car Renault 1 No. 3 A – Start 6:08 a.m.

Edmond. Former Jenatzy mechanic, has been racing on his own for a long time. Has an excellent knowledge of the anatomy of his car, which will help him on the Circuit de la Sarthe.

Fitz Shepeard. Cousin of W.K. Vanderbilt. A racing novice. An amateur who, it is said, is as good as the professionals. Hotchkiss IIT car. No. 12 c. – Dr. starts at 6:00 a.m. 18.

Barriaux. Just triumphed in the Tour de France in a small car, making his debut in the big car. Car Vulpès, will carry the number 11 A and will leave at 6.15. (Grouvelle-Arquembourg coolers.) (Simms-Bosch magneto ignition.)

Taveneaux. Has only driven buggies in races, so his car holds by far the record for lightness. Car Grégoire I, will carry the n° 9 A –and will leave at 6:12 a.m. (Continental tires) (Grouvelle-Arquembourg coolers.)

Civelli de Bosch. Won the Petit Critérium. Starts the race with a tough test, but does not despair. Car Grégoire II, (Continental tires) No. 9B – Start at 6:30 a.m.