A very extensive report of the first Indianapolis Motor Speedway three-day race meet in August 1909. As I choose to keep this extended report as a whole, you’re invited to a long read. Please don’t loose patience; it’s worth wile reading.

Text and jpegs by courtesy of hathitrust.org www.hathitrust.org, compiled by motorracinghistory.com

THE AUTOMOBILE, Vol. XXI, No. 9, August 26, 1909

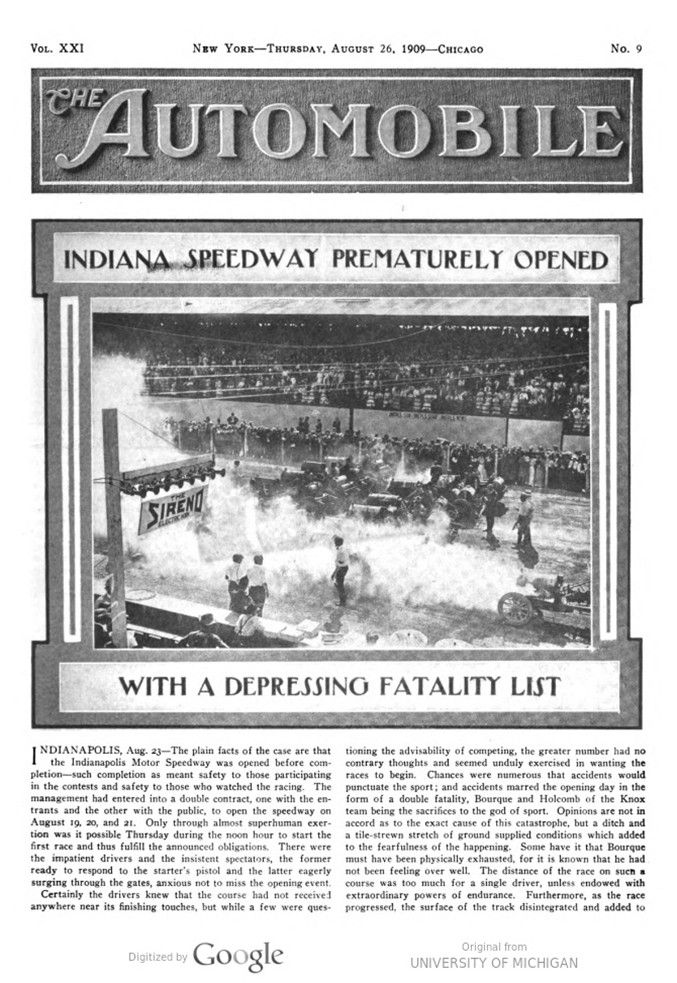

INDIANA SPEEDWAY PREMATURELY OPENED WITH A DEPRESSING FATALITY LIST

INDIANAPOLIS, Aug. 23—The plain facts of the case are that the Indianapolis Motor Speedway was opened before completion – such completion as meant safety to those participating in the contests and safety to those who watched the racing. The management had entered into a double contract, one with the entrants and the other with the public, to open the speedway on August 19, 20, and 21. Only through almost superhuman exertion was it possible Thursday during the noon hour to start the first race and thus fulfill the announced obligations. There were the impatient drivers and the insistent spectators, the former ready to respond to the starter’s pistol and the latter eagerly surging through the gates, anxious not to miss the opening event.

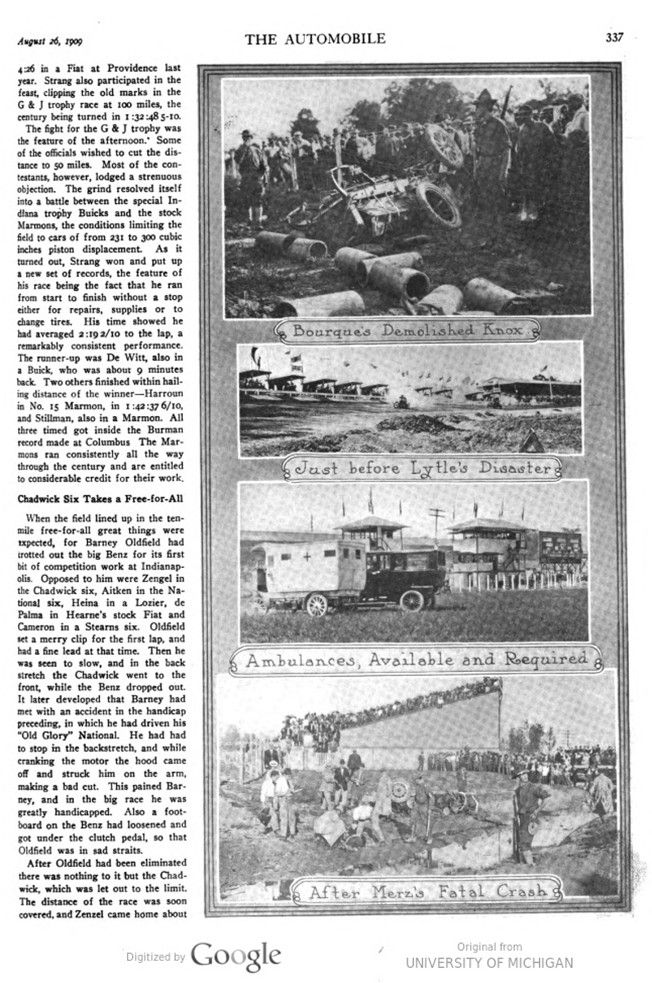

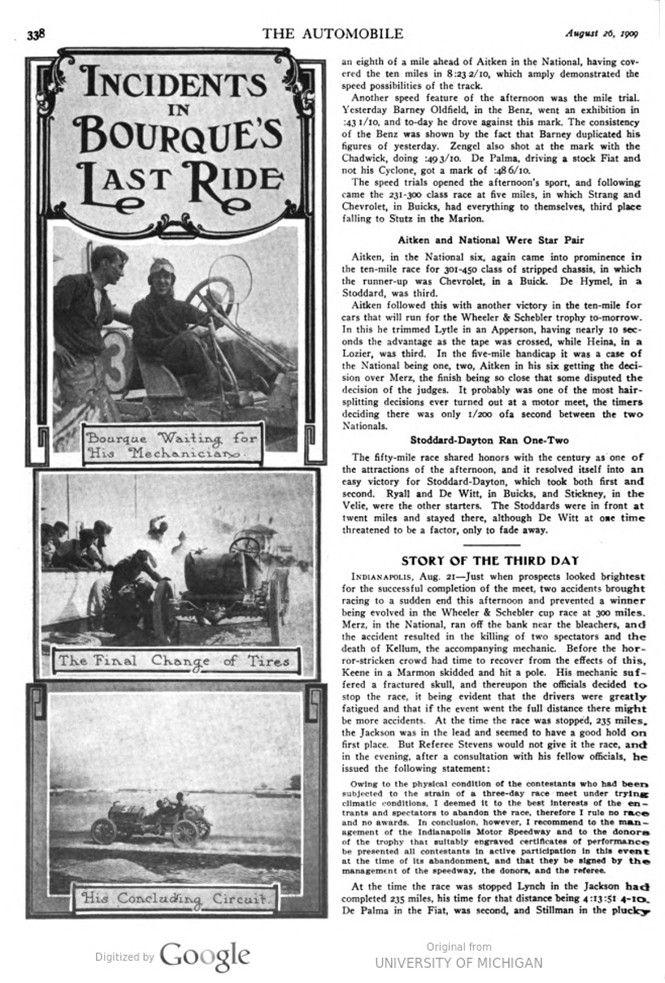

Certainly the drivers knew that the course had not received anywhere near its finishing touches, but while a few were questioning the advisability of competing, the greater number had no contrary thoughts and seemed unduly exercised in wanting the races to begin. Chances were numerous that accidents would punctuate the sport; and accidents marred the opening day in the form of a double fatality, Bourque and Holcomb of the Knox team being the sacrifices to the god of sport. Opinions are not in accord as to the exact cause of this catastrophe, but a ditch and a tile-strewn stretch of ground supplied conditions which added to the fearfulness of the happening. Some have it that Bourque must have been physically exhausted, for it is known that he had not been feeling over well. The distance of the race on such a course was too much for a single driver, unless endowed with extraordinary powers of endurance. Furthermore, as the race progressed, the surface of the track disintegrated and added to the difficulties of the task. Built at high speed, the work could not be done with the thoroughness requisite to insure a reasonable degree of permanency in the track’s surface.

Friday the thousands came again, and there was a feeling of decided relief when the sport concluded without any additions to the killed and injured list. Perhaps some were disappointed.

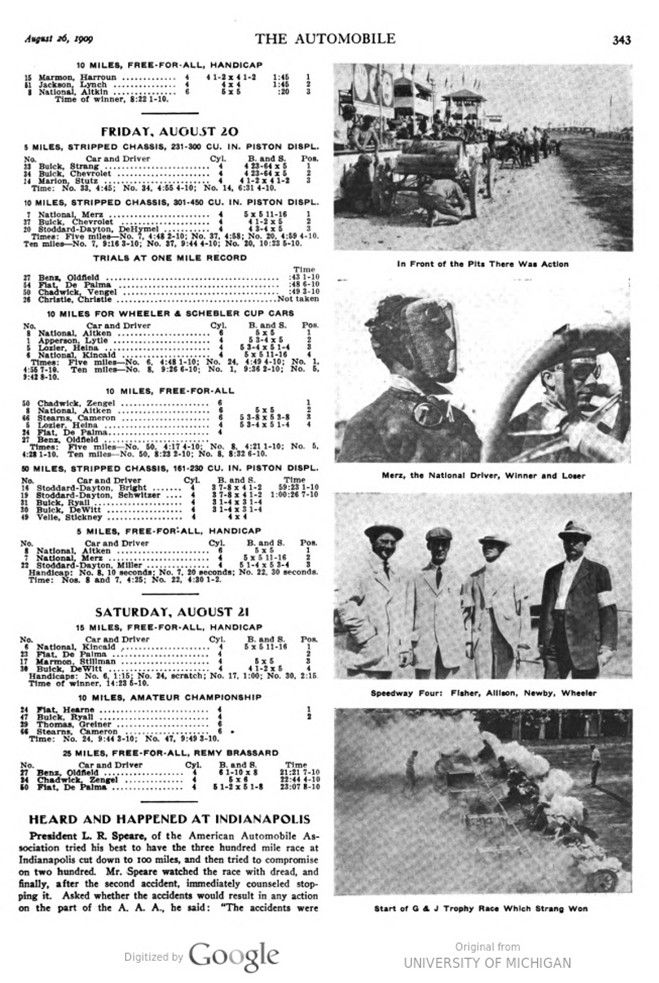

But Saturday supplied a distressing culmination, when in one accident mechanician Kellum and two spectators were killed, and another onlooker was seriously injured. This was the result of a right front tire puncture, Merz losing control of his National which dashed through the fence and turned over in the crowd near the bleachers stand. Not long after, Keene and a Marmon car met with disaster at the bridge opposite the bleachers, and it was then that Referee S. B. Stevens and President L. R. Speare of the A. A. A. decided that there had been enough for one day. Just before the announcement of this decision, the managers themselves, Messrs. Fisher, Newby, Wheeler, and Allison, had discussed and decided to ask the officials to stop the 300-mile race then in progress. At the time, the Jackson car piloted by Lynch led by over a lap, the Fiat handled by DePalma running second, with Stillman and a Marmon third.

With evident desire to leave the scene, the 25,000 spectators started homeward, some questioning the desirability of sport at the cost of human life, and others morbidly appreciating that they had seen something which they had feared might happen.

To-day there was a meeting of the directors of the speedway, when its future was carefully discussed. Taking all facts into consideration, it was decided that the track could be surrounded with safeguards, for drivers and public, which would permit a continuance of the racing, even if the expenditure totaled a hundred thousand dollars.

In commenting upon the situation, Carl G. Fisher, president of the speedway, said: „We feel there should be no more long events, longer than 100 miles, without new rules. In the first place we feel that drivers should be changed each 100 miles, as well as the tires, and we believe that drivers should be subjected to a physical examination. Loss of life must be prevented at all cost.“

Merz, who survived the Saturday casualty, is quoted as not believing in limiting events to 100 miles. Said he:

„I do not think that it is necessary to limit future races to 100 miles. Drivers can go 300 miles all right, but the track should be in good condition. I had a bad experience, but I shall drive again. At the short stretches at either end of the track too much oil had been applied and the track was slippery near the pole. During the early part of the race I kept well in, but one lap I skidded dangerously, and after that I tried it near the outer edge. It was not so slippery there, but rather rough, and severe jolting, I think, caused my tire to explode. Then it was all up with me. Even the long stretches were far too rough; all the drivers complained of it. It was really a road race.“

KNOX COMPANY IS APPRECIATIVE

SPRINGFIELD, Mass., Aug. 23-So many telegrams and letters of sympathy have been received by the Knox Automobile Company that its officials have found it necessary to acknowledge receipt of same by issuing a letter, the text of which is given herewith:

Knox Automobile Company, Springfield, Mass., August 23, 1909. Agents, Customers, and Friends:-

We have received so many expressions of sympathy and inquiries as to the probable cause of the most deplorable accident at Indianapolis, August 19, sacrificing the lives of two of our most de servedly esteemed and trusted employees, we have delayed acknowledgment until we had been privileged with an opportunity to gather as many facts as possible from our own men who were present at the time the accident occurred, and while the exact cause will never be known, we are convinced after a careful consideration of all the particulars obtainable that Mr. Bourque’s strength failed him and that he most probably lost consciousness and control of the car before it left the track.

He was not enjoying the best of health and the uncomfortable climate and track conditions demanded more than he had strength to give. He was faithful unto death and to the end enjoyed the support of a faithful helpmate.

All expressions of sympathy are fully appreciated and copies of same have been forwarded to the families of both Mr. Bourque and Mr. Holcomb. Most respectfully yours, KNOX AUTOMOBILE COMPANY.

STORY OF THE FIRST DAY

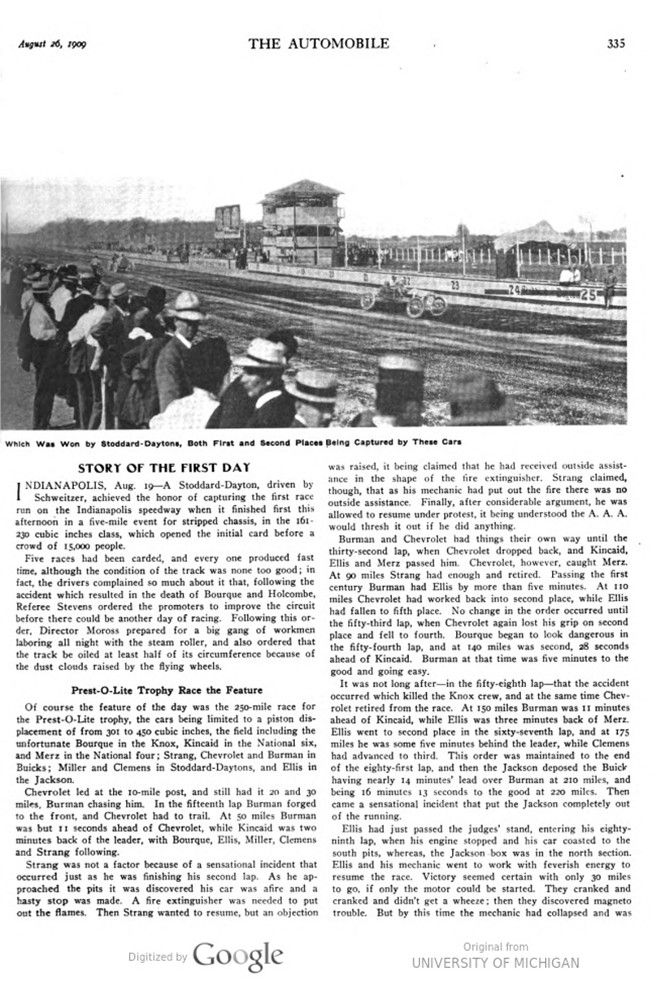

INDIANAPOLIS, Aug. 19—A Stoddard-Dayton, driven by Schweitzer, achieved the honor of capturing the first race run on the Indianapolis speedway when it finished first this afternoon in a five-mile event for stripped chassis, in the 161- 230 cubic inches class, which opened the initial card before a crowd of 15,000 people.

Five races had been carded, and every one produced fast time, although the condition of the track was none too good; in fact, the drivers complained so much about it that, following the accident which resulted in the death of Bourque and Holcombe, Referee Stevens ordered the promoters to improve the circuit before there could be another day of racing. Following this order, Director Moross prepared for a big gang of workmen laboring all night with the steam roller, and also ordered that the track be oiled at least half of its circumference because of the dust clouds raised by the flying wheels.

Prest-O-Lite Trophy Race the Feature

Of course the feature of the day was the 250-mile race for the Prest-O-Lite trophy, the cars being limited to a piston displacement of from 301 to 450 cubic inches, the field including the unfortunate Bourque in the Knox, Kincaid in the National six, and Merz in the National four; Strang, Chevrolet and Burman in Buicks; Miller and Clemens in Stoddard-Daytons, and Ellis in the Jackson.

Chevrolet led at the 10-mile post, and still had it 20 and 30 miles, Burman chasing him. In the fifteenth lap Burman forged to the front, and Chevrolet had to trail. At 50 miles Burman was but 11 seconds ahead of Chevrolet, while Kincaid was two minutes back of the leader, with Bourque, Ellis, Miller, Clemens and Strang following.

Strang was not a factor because of a sensational incident that occurred just as he was finishing his second lap. As he approached the pits it was discovered his car was afire and a hasty stop was made. A fire extinguisher was needed to put out the flames. Then Strang wanted to resume, but an objection was raised, it being claimed that he had received outside assistance in the shape of the fire extinguisher. Strang claimed, though, that as his mechanic had put out the fire there was no outside assistance. Finally, after considerable argument, he was allowed to resume under protest, it being understood the A. A. A. would thresh it out if he did anything.

Burman and Chevrolet had things their own way until the thirty-second lap, when Chevrolet dropped back, and Kincaid, Ellis and Merz passed him. Chevrolet, however, caught Merz. At 90 miles Strang had enough and retired. Passing the first century Burman had Ellis by more than five minutes. At 110 miles Chevrolet had worked back into second place, while Ellis had fallen to fifth place. No change in the order occurred until the fifty-third lap, when Chevrolet again lost his grip on second place and fell to fourth. Bourque began to look dangerous in the fifty-fourth lap, and at 140 miles was second, 28 seconds ahead of Kincaid. Burman at that time was five minutes to the good and going easy.

It was not long after — in the fifty-eighth lap — that the accident occurred which killed the Knox crew, and at the same time Chevrolet retired from the race. At 150 miles Burman was 11 minutes ahead of Kincaid, while Ellis was three minutes back of Merz. Ellis went to second place in the sixty-seventh lap, and at 175 miles he was some five minutes behind the leader, while Clemens had advanced to third. This order was maintained to the end of the eighty-first lap, and then the Jackson deposed the Buick having nearly 14 minutes‘ lead over Burman at 210 miles, and being 16 minutes 13 seconds to the good at 220 miles. Then came a sensational incident that put the Jackson completely out of the running.

Ellis had just passed the judges‘ stand, entering his eighty- ninth lap, when his engine stopped and his car coasted to the south pits, whereas, the Jackson box was in the north section. Ellis and his mechanic went to work with feverish energy to resume the race. Victory seemed certain with only 30 miles to go, if only the motor could be started. They cranked and cranked and didn’t get a wheeze; then they discovered magneto trouble. But by this time the mechanic had collapsed and was carried off the track by Ellis, who was all in himself. The exertion told on him, and he, too, fainted. Thereupon Referee Stevens granted permission for a relief crew to go on, and Tom Lynch undertook the job of piloting. But he also failed to get the engine started, and the dead Jackson stood by the pits while Burman continued on to victory, Clemens being runner-up, while Merz, in the No. 7 National, went into third place 7 when his team mate, Kincaid, failed to get to the tape because of a broken gasoline feed on his last round.

Oldfield Benzed Mile Mark

Despite the roughness of the track, Barney Oldfield, in the Benz, set a mile mark that is likely to stand for some time, doing an exhibition in :43 1-10. Of course these figures have been excelled in road and beach trials, but it is the best ever made on a track in this country.

Wright and Schweitzer in Stoddard-Daytons, De Witt and Ryall in Buicks and Stickney in a Velie were the starters in the opener. Ryall went out the first lap and the Velie was not a contender. The three cars that did fight it out went at a good clip, the time of the winner being 5:13 2-10.

Poor “Billy“ Bourque scored his last victory in the five-mile stripped chassis race for cars in the 301-450 class when he showed the way home to Clemens in a Stoddard-Dayton and Merz in the National, his time being 4:45 1-5. In this an attempt was made to use a flying start, but there was so much trouble in doing it this way that Starter Wagner went back to the standing start.

Harroun, of Chicago, driving a Marmon, won the 10-mile free-for-all handicap, in which a good field started. He had a 1:45 handicap.

STORY OF SECOND DAY

INDIANAPOLIS, Aug. 20—The G & J trophy at 100 miles and a 50-mile event furnished the attractions to-day, and six events were run off without accidents of any sort. Proceedings began at noon, and by 1 o’clock there were at least 20,000 spectators. By working all night the management had put the course in better shape than it was on the first day, the surface having been oiled half way around, while the work of the steam rollers was easily noticeable. Zengel in the Chadwick six clipped off 10 miles in 8:23 1-10 as against the 9:12 3-5 made by Oldfield in his Peerless Green Dragon as far back as 1904. Aitken in the National six ran 5 miles in 4:25 as against DePalma’s 4:26 in a Fiat at Providence last year. Strang also participated in the feast, clipping the old marks in the G & J trophy race at 100 miles, the century being turned in 1:32:48 5-10.

The fight for the G & J trophy was the feature of the afternoon. Some of the officials wished to cut the distance to 50 miles. Most of the contestants, however, lodged a strenuous objection. The grind resolved itself into a battle between the special Indiana trophy Buicks and the stock Marmons, the conditions limiting the field to cars of from 231 to 300 cubic inches piston displacement. As it turned out, Strang won and put up a new set of records, the feature of his race being the fact that he ran from start to finish without a stop either for repairs, supplies or to change tires. His time showed he had averaged 2:19 2/10 to the lap, a remarkably consistent performance. The runner-up was De Witt, also in a Buick, who was about 9 minutes back. Two others finished within hailing distance of the winner-Harroun in No. 15 Marmon, in 1:42:37 6/10, and Stillman, also in a Marmon. All three timed got inside the Burman record made at Columbus. The Marmons ran consistently all the way through the century and are entitled to considerable credit for their work.

Chadwick Six Takes a Free-for-All

When the field lined up in the ten-mile free-for-all great things were expected, for Barney Oldfield had trotted out the big Benz for its first bit of competition work at Indianapolis. Opposed to him were Zengel in the Chadwick six, Aitken in the National six, Heina in a Lozier, de Palma in Hearne’s stock Fiat and Cameron in a Stearns six. Oldfield set a merry clip for the first lap, and had a fine lead at that time. Then he was seen to slow, and in the back stretch the Chadwick went to the front, while the Benz dropped out. It later developed that Barney had met with an accident in the handicap preceding, in which he had driven his „Old Glory“ National. He had had to stop in the backstretch, and while cranking the motor the hood came off and struck him on the arm, making a bad cut. This pained Barney, and in the big race he was greatly handicapped. Also a foot-board on the Benz had loosened and got under the clutch pedal, so that Oldfield was in sad straits.

After Oldfield had been eliminated there was nothing to it but the Chadwick, which was let out to the limit. The distance of the race was soon covered, and Zengel came home about an eighth of a mile ahead of Aitken in the National, having covered the ten miles in 8:23 2/10, which amply demonstrated the speed possibilities of the track.

Another speed feature of the afternoon was the mile trial. Yesterday Barney Oldfield, in the Benz, went an exhibition in :43 1/10, and to-day he drove against this mark. The consistency of the Benz was shown by the fact that Barney duplicated his figures of yesterday. Zengel also shot at the mark with the Chadwick, doing :49 3/10. De Palma, driving a stock Fiat and not his Cyclone, got a mark of :48 6/10.

The speed trials opened the afternoon’s sport, and following came the 231-300 class race at five miles, in which Strang and Chevrolet, in Buicks, had everything to themselves, third place falling to Stutz in the Marion.

Aitken and National Were Star Pair

Aitken, in the National six, again came into prominence in the ten-mile race for 301-450 class of stripped chassis, in which the runner-up was Chevrolet, in a Buick. De Hymel, in a Stoddard, was third.

Aitken followed this with another victory in the ten-mile for cars that will run for the Wheeler & Schebler trophy to-morrow. In this he trimmed Lytle in an Apperson, having nearly 10 seconds the advantage as the tape was crossed, while Heina, in a Lozier, was third. In the five-mile handicap it was a case of the National being one, two, Aitken in his six getting the decision over Merz, the finish being so close that some disputed the decision of the judges. It probably was one of the most hair-splitting decisions ever turned out at a motor meet, the timers deciding there was only 1/200 of a second between the two Nationals.

Stoddard-Dayton Ran One-Two

The fifty-mile race shared honors with the century as one of the attractions of the afternoon, and it resolved itself into an easy victory for Stoddard-Dayton, which took both first and second. Ryall and De Witt, in Buicks, and Stickney, in the Velie, were the other starters. The Stoddards were in front at twent miles and stayed there, although De Witt at one time threatened to be a factor, only to fade away.

STORY OF THE THIRD DAY

INDIANAPOLIS, Aug. 21—Just when prospects looked brightest for the successful completion of the meet, two accidents brought racing to a sudden end this afternoon and prevented a winner being evolved in the Wheeler & Schebler cup race at 300 miles. Merz, in the National, ran off the bank near the bleachers, and the accident resulted in the killing of two spectators and the death of Kellum, the accompanying mechanic. Before the horror-stricken crowd had time to recover from the effects of this, Keene in a Marmon skidded and hit a pole. His mechanic suffered a fractured skull, and thereupon the officials decided to stop the race, it being evident that the drivers were greatly fatigued and that if the event went the full distance there might be more accidents. At the time the race was stopped, 235 miles, the Jackson was in the lead and seemed to have a good hold on first place. But Referee Stevens would not give it the race, and in the evening, after a consultation with his fellow officials, he issued the following statement:

Owing to the physical condition of the contestants who had been subjected to the strain of a three-day race meet under trying climatic conditions, I deemed it to the best interests of the entrants and spectators to abandon the race, therefore I rule no race and no awards. In conclusion, however, I recommend to the management of the Indianapolis Motor Speedway and to the donors of the trophy that suitably engraved certificates of performance be presented all contestants in active participation in this event at the time of its abandonment, and that they be signed by the management of the speedway, the donors, and the referee.

At the time the race was stopped Lynch in the Jackson had completed 235 miles, his time for that distance being 4:13:51 4-10. De Palma in the Fiat, was second, and Stillman in the plucky little Marmon third. Harroun in a Marmon, and De Hymel in a Stoddard, were also running—five out of eighteen starters.

The race itself was replete with sensational incidents. At the very start Johnny Aitken in the National six jumped out and beat it. He soon had a good lead over his fellows, with Lytle in the Apperson being closest. The half-century showed Aitken more than three minutes to the good.

Lytle Figured in the First Accident

The first scare of the afternoon came in the twenty-fourth lap when Lytle escaped a serious accident by his skillful driving. He had just passed th pits when a steering arm broke and left Lytle almost helpless. The car made a wild dive for the fence, but Lytle with control only over one front wheel managed to pull it away and run up the bank. He had slowed by this time and from the top of the bank he slowly drifted to the pole, just escaping being hit by one of the cars following him. When the bottom was reached the Apperson struck a pile of dirt, the mechanic was thrown clear and Lytle stepped out unhurt. The car had been moving so slowly that no damage was done. Lytle went to work and repaired the damage and resumed when the race had reached 175 miles. He was so far behind, though, that he hadn’t a chance in the world of doing anything.

Following the Apperson incident Aitken continued to burn it and had turned the century with a new record to his credit. The National was running so well that even at this early point it seemed as if Aitken’s name would be the first engraved on the $10,000 trophy. But in the very next lap a cracked cylinder developed and Aitken had to quit, leaving an opening for Burman to become the leader. The Buick star went to the front and showed first at 125 miles, but soon after he went down and out, leaving the field to Lynch in the Jackson, De Palma in the Fiat, and Stillman in the Marmon.

How Kellum Ran to His Death

Merz in the National four still was in the running and for a few laps after his team mate had quit he had been in front. Trouble overtook him though when he had to stop in the back stretch. He stopped his engine and when he tried to start it again he discovered his storage battery was dead. He and his mechanic, Lyne, were too tired to start on the magneto and so Lyne was dispatched across the infield for a new battery. It was a long run, nearly a mile, and Lyne arrived at the pit in an exhausted condition, collapsing when he reached there, whereupon Kellum was delegated to take his place. Kellum had been mechanic for Aitken until the six had been forced out, but he cheerfully picked up the battery and ran across the field with it, going to his death, as it afterward turned out.

Merz started to recover lost ground and was making good progress. He had passed the double century mark and had swung into the first turn. He had got half way around the bend and was nearing the bleachers when a front right tire punctured. The National shot up the bank and over the edge just where the bridge abutment is located. It posed for a second on the brink, then toppled over, striking a fence on which sat a row of spectators. It was a danger point and there was a huge sign there warning people to keep away, and it is stated that the police had driven them off several times. The crash of the car killed two outright, Ora Joliffe of Trafalgar, Ind., and an unknown man. Kellum was so badly injured that he died soon after. Merz, though, had a lucky escape. He was caught under the car when it turned over but was not hurt, retaining presence of mind enough to turn off the power before he crawled out.

Only three other races were run and there was an attack on the kilometer record which resulted in Oldfield in the Benz going the 5-8 of a mile in :26 2-10. Christie did :28 7-10, and Zengel in the Chadwick :29 9-10.

Oldfield Won the Remy Brassard

A remarkably fast race was run for the Remy brassard, which has been put up by the magneto manufacturer and which carries with it a salary of $75 a week as long as it is held. Oldfield went after the money and got it, leaving behind him a trail of new records. He finished the quarter-century in 21:21 7-10, the Fiat being second in 22:44 4-10, and the Chadwick third in 23:07 8-10.

HEARD AND HAPPENED AT INDIANAPOLIS

President L. R. Speare, of the American Automobile Association tried his best to have the three hundred mile race at Indianapolis cut down to 100 miles, and then tried to compromise on two hundred. Mr. Speare watched the race with dread, and finally, after the second accident, immediately counseled stop- ping it. Asked whether the accidents would result in any action on the part of the A. A. A., he said: „The accidents were the result of conditions which may be corrected, and will be. I see no reason now for raising any bars against future contests.

As in the days of cycle racing, the public has grown to believe in the man as much as in the machine, and the cheers are for the men with whom, through past performances, they are acquainted. In the grand stands at events will be heard: „What do you know about that. Barney has just let that fellow go by him. Why don’t he hurry up. Barney is not a quitter.“ These and similar remarks show plainly the feeling of the people and add zest to the sport which was not there in the early days when the feeling was general that it was the machine and not the man that was doing the racing.

“Go out, boys, and do your best to win, but without taking chances,” said Mr. Wright of Springfield when Dennison and Bourque left for Indianapolis. „Remember,“ continued Mr. Wright, “you boys are very dear to us here, and we want no wins at the sacrifice of safety. We merely want you to drive within the safety limit, but finish the contest.“ Dennison promised, as did Bourque.

„No married men need apply,“ is the verdict of one maker of automobiles who oftentimes dabs in speed contests. This maker issued the edict before sending his team to Indianapolis, and by a chance a married did get on the team. The man was killed, but not at the track, and the wife, of course, blamed it all to the maker, although the husband had always claimed that he was not married and steadily carried through the deception to gain a place on the racing cars.

BOURQUE WAS TO HAVE BEEN MARRIED

SPRINGFIELD, Mass., Aug. 22—Wilfred Bourque, who was killed while competing in the automobile races at Indianapolis last Thursday, was to have been married September 14 to Miss Alexina Boivin, of West Springfield, and two of their friends, Prosper Dufresne and Miss Eugenie Parent, had planned to make the wedding a double ceremony. Bourque’s fiancée was opposed to his racing, and he had promised her that after the Vanderbilt cup event this fall he would not race another car.

Over 300 employees of the Knox Automobile Company met the bodies of Bourque and Harry Holcomb on their arrival from the West and escorted them to their homes. Fully 5,000 persons were at the railroad station when the train arrived.

The funeral of Mr. Holcomb was held this afternoon in the Methodist Church in Granville, the Rev. Philip L. Frick officiating. The funeral of Mr. Bourque will be held to-morrow morning at St. Louis‘ Church in West Springfield.

STODDARD-DAYTON OUT OF RACING

DAYTON, O., Aug. 24-Charles G. Stoddard, vice-president of the Dayton Motor Car Company, announced to-day that the local company would never again enter in a racing event. The Dayton concern conducted a large excursion to the recent meet at Indianapolis, when 1,800 residents of this city saw the races and accidents which marred the sport.

Mr. Stoddard says automobile races not only cause men to risk their lives unnecessarily, but that the motor car business is damaged every time a man is hurt.

Photo captions.

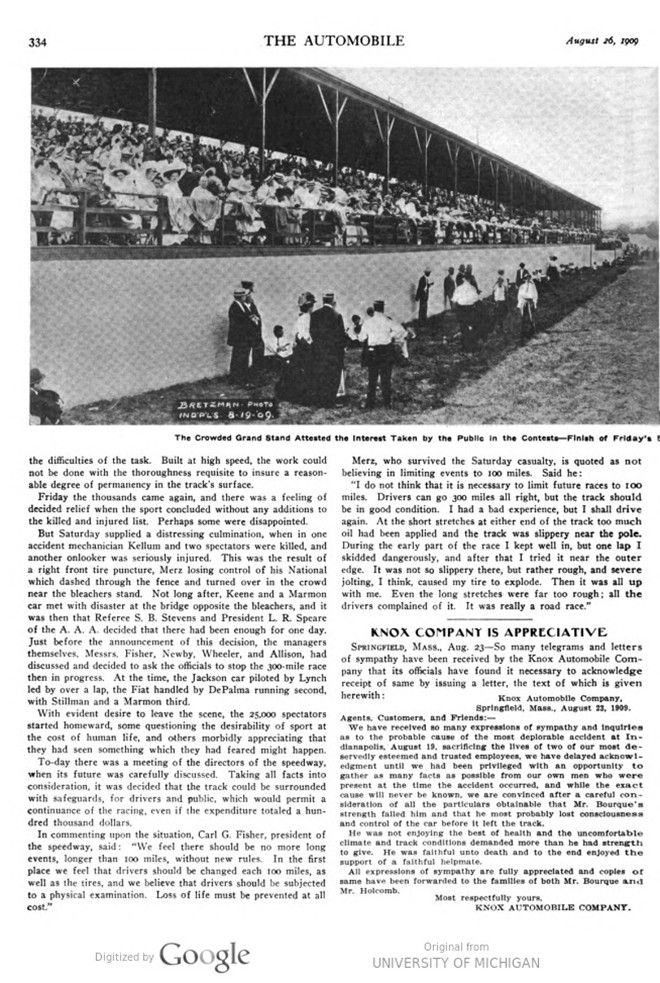

BRETZMAN. PHOTO INDPLS. 8-19-09. The Crowded Grand Stand Attested the Interest Taken by the Public in the Contests – Finish of Friday’s Race Which Was Won by Stoddard-Daytons, Both First and Second Places Being Captured by These Cars

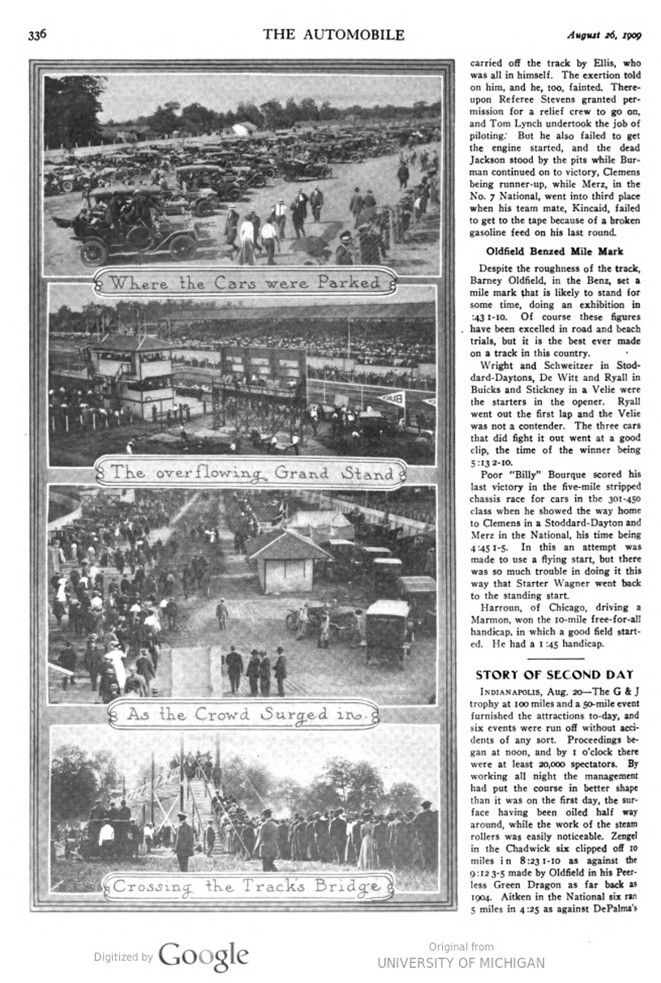

Where the Cars were Parked – The overflowing Grand Stand – As the Crowd Surged in. – Crossing the Track’s Bridge

Bourques Demolished Knox – Just before Lytle’s Disasters – Ambulances, Available and Required – After Merz’s Fatal Crash

INCIDENTS IN BOURQUE’S LAST RIDE – Bourque Waiting for His Mechanician. – The Final Change of Tires. – His Concluding Circuit.

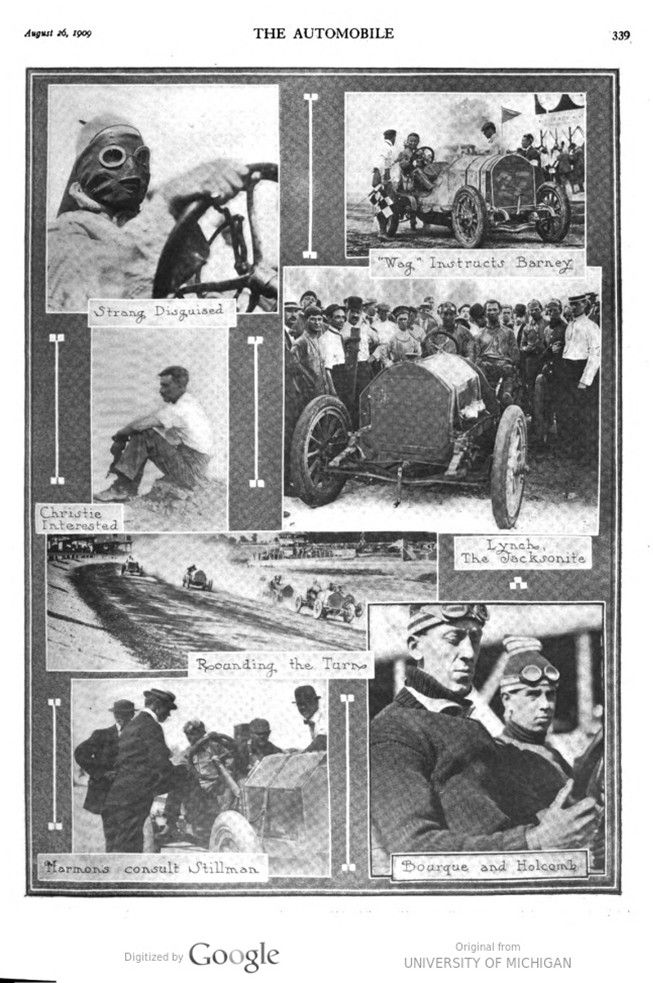

Strang Disguised – Christie Interested – Rounding the Turns – „Wag“ Instructs Barney – Lynch, The Jacksonite – Marmons consult Stillman – Bourque and Holcomb

Time-Keepers Baker and Warner – F. H.Wheeler – One Contestant and Some Officials – Busy Moross – The Gold-Plated Overland – Referee Stevens – A.G.Candler, Jr., and EM. Durant of Atlanta – Technicist Beecroft – A.L. Riker, C.W. Kelsey. Mr. and Mrs. H E. Coffing

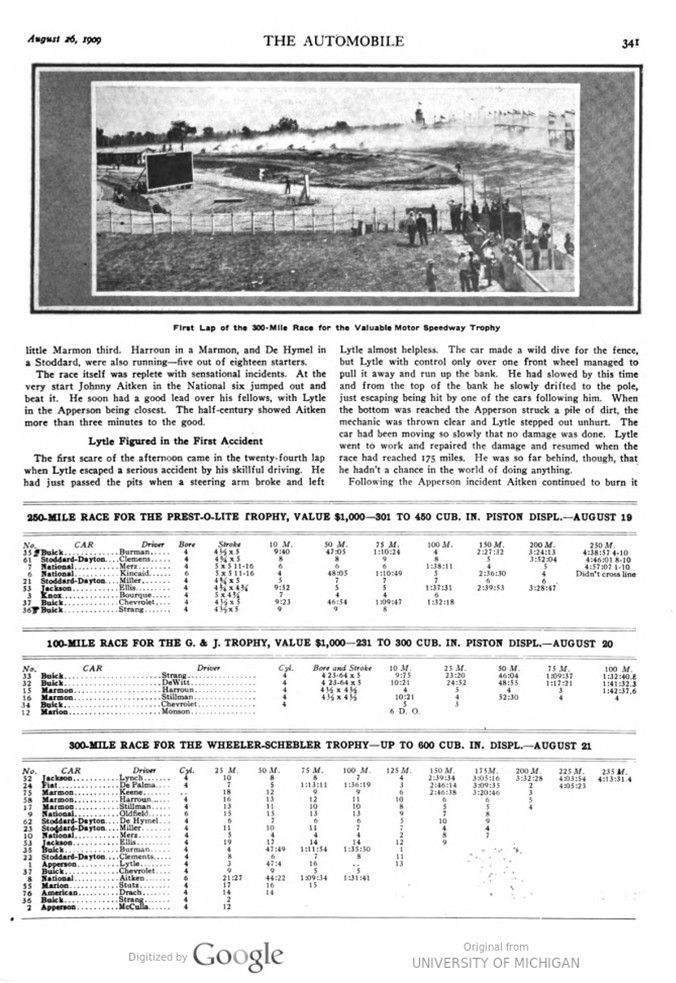

First Lap of the 300-Mile Race for the Valuable Motor Speedway Trophy

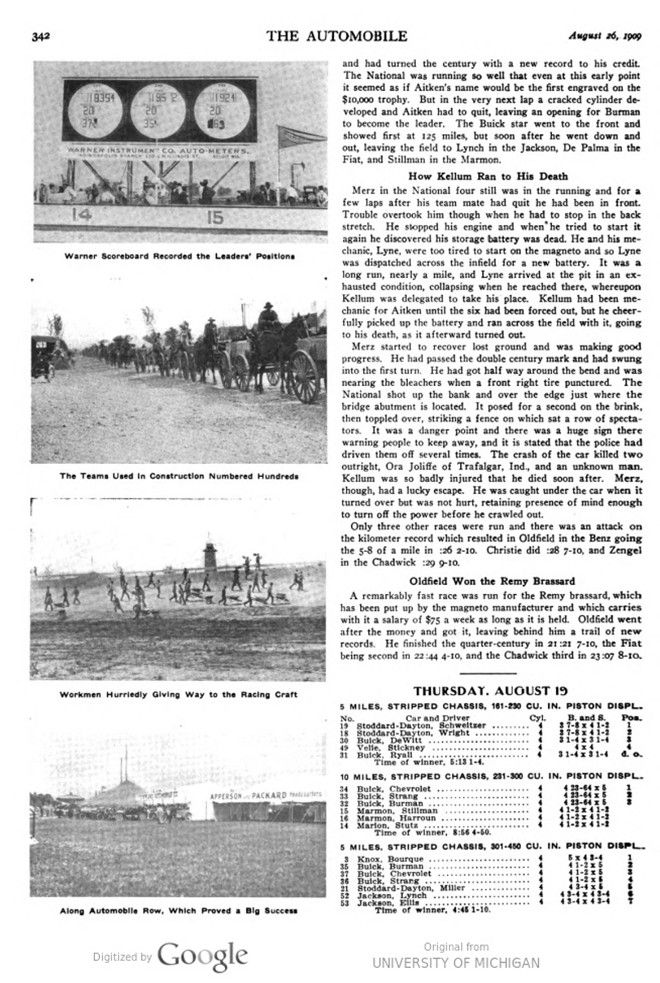

WARNER INSTRUMEN CO. AUTO-METERS. INDIANAPOLIS BRANCH 330 N. ILLINOIS Warner Scoreboard Recorded the Leaders‘ Positions – The Teams Used In Construction Numbered Hundreds – Workmen Hurriedly Giving Way to the Racing Craft – Along Automobile Row, Which proved a Big Success

In Front of the Pits There Was Action – Merz, the National Driver, Winner and Loser – Speedway Four: Fisher, Allison, Newby, Wheeler – Start of G & J Trophy Race Which Strang Won