This article was published in The Saturday Evening Post of January 5th 1941, just some 45 years after the event took place. Written by Herman Henry (H. H.) Kohlsaat (1853-1924), reportedly editor and publisher of the Times-Herald newspaper, the originator of this first vehicle event in America. He got the idea of a carriage contest, when reading an article in the French l’Illustation on the June 1895 Paris-Bordeaux race. It looks like newspapers were prepared to orgaize and donate quite some money for horseless carriage contests in those early days of motoring. In the US, it was the Chicago Time-Herald and in France, the Paris based Le Petit Journal.

Text and photos with courtesy of The Saturday Evening Post saturdayeveningpost.com, compiled by motorracinghistory.

The Saturday Evening Post (January 5, 1941)

America’s First Horseless Carriage Race, 1895 – By H. H. Kohlsaat.

IN MAY, 1895, in the Chicago Club, I picked up a copy of L’Illustration, of Paris, containing an account, with illustrations, of an automobile race between Paris and Bordeaux which had taken place a few weeks before. It gave me an idea. On my return to The Times Herald office, I purchased a copy of L’Illustration and called into my room Frederick U. Adams, known to the newspaper profession as Grizzly Adams. Mr. Adams had a mechanical twist of mind, rare in a reporter. I showed him the report of the French race and suggested that The Times Herald get up a contest in Chicago of horseless vehicles. Adams was enthusiastic and at once drew up a plan which I indorsed and published. The Times Herald offered five thousand dollars in prizes and five thousand dollars to pay the preliminary expenses.

The race was to be run July 4, 1895. Some sixty contestants entered the lists. The interest of inventors was great. Most of them were without financial means and made my life a burden, showing me their drawings and asking for money to develop their ideas, so I asked President Cleveland to have the War Department take charge of the experiments and race. He instructed General Miles to appoint someone to supervise the contest.

My appeal to Mr. Cleveland was based on the belief that the greatest use of the motor wagon would be for army and commercial trucks. The Times Herald made the prediction that in twenty years horses would be used for pleasure vehicles only.

The President approved of General Miles‘ appointment of Gen. Wesley Merritt. He came to Chicago, and I turned over the management to him. General Merritt chose Henry Timken, a carriage manufacturer, and Prof. John P. Barrett, head of the Electricity Department of Chicago, to act as judges with him, and as assistant judges, Leland L. Summers and John Lundie, civil engineers; Col. M. J. Ludington, United States Army; Dr. Allan Hornsby, and C. F. Kimball, carriage manufacturer of Chicago.

A testing apparatus was set up. It was unique from the fact that the result to be obtained had never been sought anywhere else in the world. It was designed by Leland L. Summers, the twenty-six-year-old editor of Electrical Engineering, and John Lundie, a young Englishman.

Upon the two young men fell the bulk of the work of showing the consumption of fuel and the efficiency of the machines. A platform with a 15 per cent incline was built and each machine entering was subject to the test.

Ditched by a Nervous Farmer

WHEN July Fourth arrived, there was only one machine ready-the Haynes-Apperson, of Kokomo, Indiana.

As it was impossible to have a contest with one machine, the time was extended to Labor Day, in September. In August 1 was again requested to postpone the date, so fixed Thanksgiving Day, November twenty-eighth.

There was considerable opposition to calling the horseless carriage „automobile,“ as the name was too Frenchy, so The Times Herald offered five hundred dollars for a name, and „motocycle“ was awarded the prize.

October 15, 1895, two ambitious young men started a magazine, calling it the Motocycle. It was the first of its kind published in America. The Horseless Age, of New York, was started November first, fifteen days later. The Motocycle issued two numbers only, October and November, and gave up the ghost. There was so little general interest in the new motive power, outside of the manufacturers of carriages and buggies, that the subscribers were few, and advertising nil.

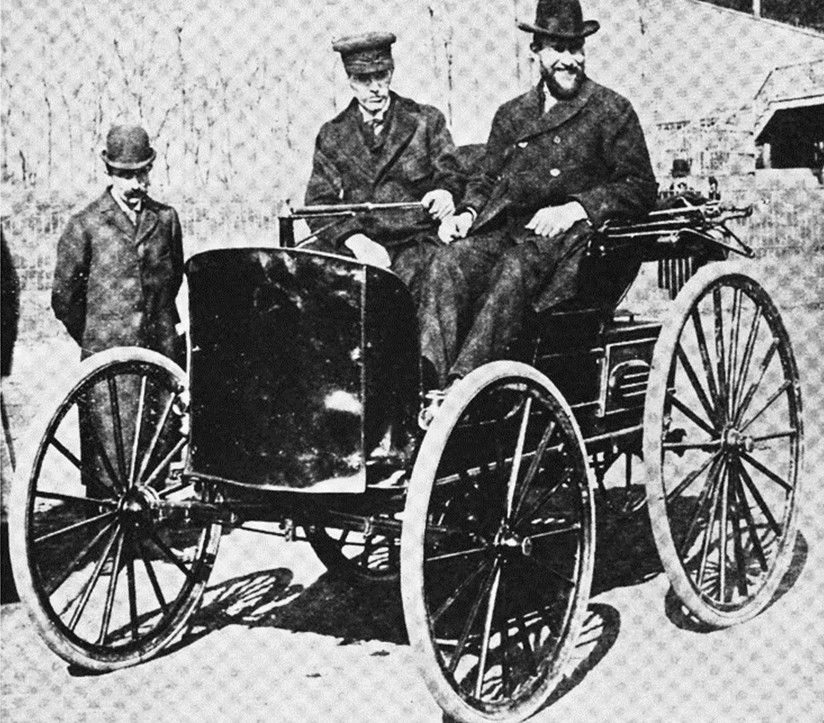

A purse of five hundred dollars was, while waiting for the Thanksgiving Day event, put up for a race between the H. Mueller Benz Gasoline Motor, of Decatur, Illinois, and the Duryea Gasoline Motor Wagon, of Springfield, Massachusetts. The course was to Waukegan, Illinois, and back, a distance of ninety-two miles, with a time limit of thirteen hours. The start was made November second, from Washington Park. The race ended at the Grant Monument in Lincoln Park. Mr. Mueller was awarded the prize, making the round trip in nine and a half hours.

The Duryea motor ran into a ditch to avoid a farmer who turned his horses to the left instead of the right. He said he was so scared to see a buggy without any horses hitched to it coming up the road behind him, he did not know what he was doing. To avoid a collision Mr. Duryea, who was driving this motor, drove into the ditch, hoping to climb up the slight embankment, but broke a wheel and gave up the race. He hauled his machine to the nearest depot and shipped it to Chicago, where it was repaired.

This car entered the real contest on Thanksgiving Day, winning the first prize, two thousand dollars.

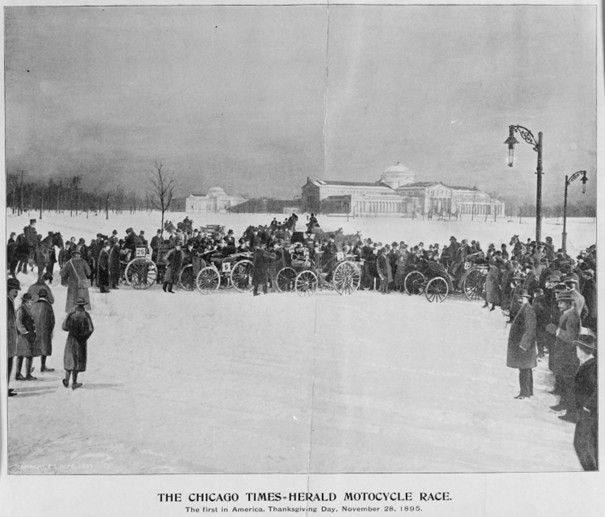

The night before Thanksgiving, two or three inches of snow fell, making a severe test for the motors. The Times Herald arranged with the park commissioners to give the machines the right of way, as up to that time they had been barred from the boulevards to avoid frightening the horses. The official course was from the World’s Fair German Building, in Jackson Park, to Evanston and return, fifty-three and a half miles.

The evening before the race eleven competitors out of the sixty-odd entrants declared they would start, but when the motors were sent on their fifty-three-and-a-half mile run only six reached the starting point, the others breaking down en route.

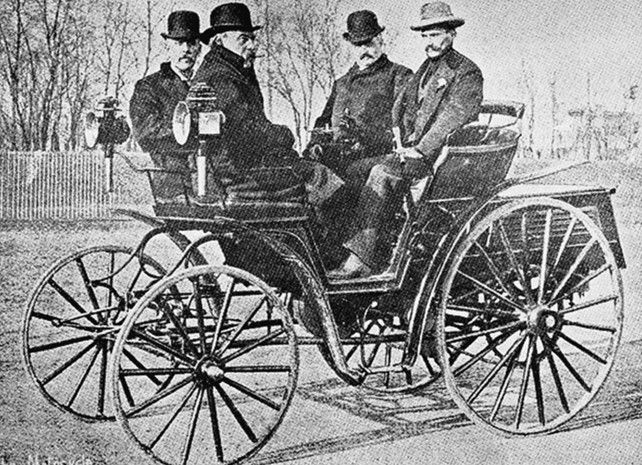

The six lined up at the post were:

The Duryea Wagon Motor Company, Springfield, Massachusetts, using gasoline;

The De La Vergne Refrigerator Machine Company, gasoline;

The Morris and Salom, Philadelphia, electric;

H. Mueller & Co., Decatur, Illinois, gasoline;

R. H. Macy, New York, gasoline;

The Sturges Electric, of Chicago.

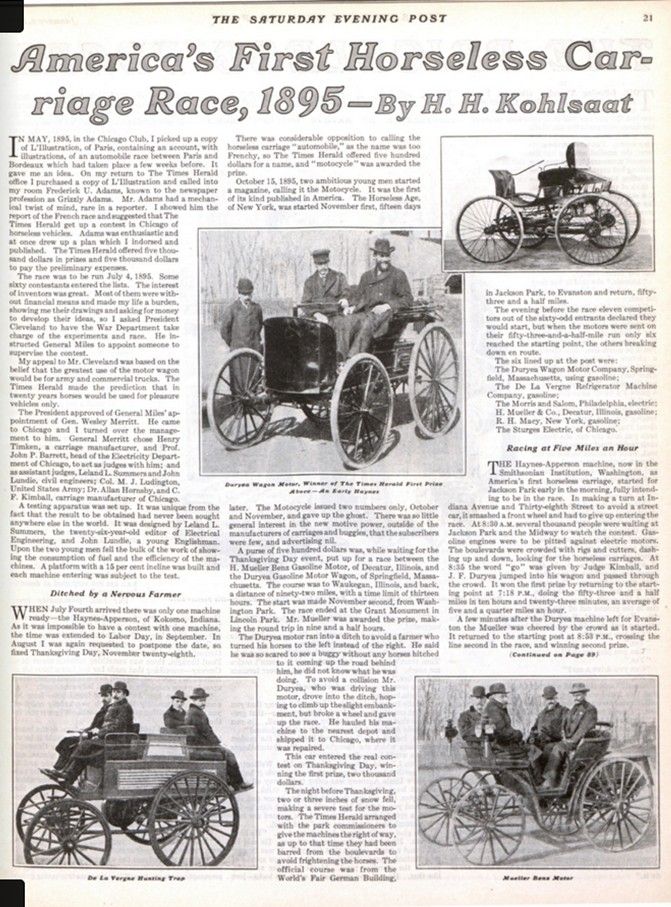

Racing at Five Miles an Hour

THE Haynes-Apperson machine, now in the Smithsonian Institution, Washington, as America’s first horseless carriage, started for Jackson Park early in the morning, fully intending to be in the race. In making a turn at Indiana Avenue and Thirty-eighth Street to avoid a street car, it smashed a front wheel and had to give up entering the race. At 8:30 A.M. several thousand people were waiting at Jackson Park and the Midway to watch the contest. Gasoline engines were to be pitted against electric motors. The boulevards were crowded with rigs and cutters, dashing up and down, looking for the horseless carriages. At 8:35 the word „go“ was given by Judge Kimball, and J. F. Duryea jumped into his wagon and passed through the crowd. It won the first prize by returning to the starting point at 7:18 P.M., doing the fifty-three and a half miles in ten hours and twenty-three minutes, an average of five and a quarter miles an hour.

A few minutes after the Duryea machine left for Evanston the Mueller was cheered by the crowd as it started. It returned to the starting post at 8:53 P.M., crossing the line second in the race and winning second prize.

The thousands lining the boulevards were not greatly impressed with the future of the motor car. In the first place, the love of the horse, an instinct of the human race,

prejudiced the crowd against the ugly motors, which were generally buggies with the shafts taken off. Again, the constant breakdowns did not add to the interest of the new toy, as it was called.

The Chicago Tribune, with ridicule, was the only paper that mentioned the race at all and echoed, I believe, the general sentiment by printing three inches of space under the caption Old Dobbin is Still in the Ring.

The four other machines that started broke down and did not finish the race. Out of the sixty-odd entrants of America’s first horseless-carriage race only two were able to go the fifty-three and a half miles with an average speed of five and a quarter miles an hour.

In 1914 I visited Detroit and carried a copy of The Motocycle of 1895. A friend suggested I show the magazine to Henry Ford and arranged a meeting by telephone. After lunch I showed Mr. Ford the book. He went over it page by page with eager interest and remarked, „I never wanted anything so badly in my life as to go to that race, but I could not get anyone to loan me the car fare to Chicago.“ My banker friend said the day he made the remark Mr. Ford had twenty-eight million dollars in bank subject to his check.

Official Report of the Race

FREDERICK U. ADAMS, who had charge of the race for H. H. Kohlsaat, said that the contest was satisfactory in every particular and that the tests threw those made recently in France far in the rear. „The Paris-Bordeaux race,“ he commented, „was worthless from a scientific standpoint, but the contest of today may result in the establishment of good data concerning what many believe the vehicle of the future. The progress of the preliminary tests has been watched by thousands of manufacturers in every part of the world, and there is no doubt that there will be a great interest in the manufacture of these horseless vehicles, now that it has been demonstrated what can be done with them.“

Several Breakdowns

THE victory of the Duryea machine was all the more remarkable as this was the one which broke down in the minor race a month before. Under the box of the vehicle and at the rear there were two chains which broke several times, but Mr. Duryea succeeded in repairing them so as to avoid much delay. This inventor was working on two machines which he expected to enter for the race in the place of the one which was successful, but the time was not long enough to allow of their completion.

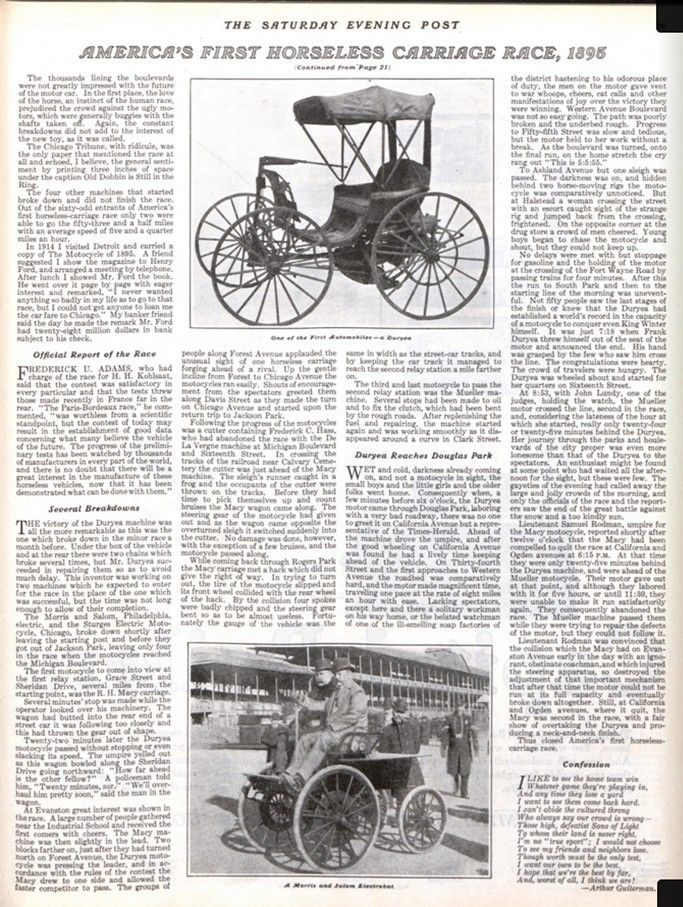

The Morris and Salom, Philadelphia, electric, and the Sturges Electric Motocycle, Chicago, broke down shortly after leaving the starting post and before they got out of Jackson Park, leaving only four in the race when the motocycles reached the Michigan Boulevard.

The first motocycle to come into view at the first relay station, Grace Street and Sheridan Drive, several miles from the starting point, was the R. H. Macy carriage.

Several minutes‘ stop was made while the operator looked over his machinery. The wagon had butted into the rear end of a street car it was following too closely and this had thrown the gear out of shape.

Twenty-two minutes later the Duryea motocycle passed without stopping or even slacking its speed. The umpire yelled out as this wagon bowled along the Sheridan Drive going northward: „How far ahead is the other fellow?“ A policeman told him, „Twenty minutes, sor.“ „We’ll overhaul him pretty soon,“ said the man in the wagon.

At Evanston great interest was shown in the race. A large number of people gathered near the Industrial School and received the first comers with cheers. The Macy machine was then slightly in the lead. Two blocks farther on, just after they had turned north on Forest Avenue, the Duryea motocycle was pressing the leader, and in accordance with the rules of the contest the Macy drew to one side and allowed the faster competitor to pass. The groups of people along Forest Avenue applauded the unusual sight of one horseless carriage forging ahead of a rival. Up the gentle incline from Forest to Chicago Avenue the motocycles ran easily. Shouts of encouragement from the spectators greeted them along Davis Street as they made the turn on Chicago Avenue and started upon the return trip to Jackson Park.

Following the progress of the motocycles was a cutter containing Frederick C. Hass, who had abandoned the race with the De La Vergne machine at Michigan Boulevard and Sixteenth Street. In crossing the tracks of the railroad near Calvary Cemetery the cutter was just ahead of the Macy machine. The sleigh’s runner caught in a frog and the occupants of the cutter were thrown on the tracks. Before they had time to pick themselves up and count bruises the Macy wagon came along. The steering gear of the motocycle had given out and as the wagon came opposite the overturned sleigh it switched suddenly into the cutter. No damage was done, however, with the exception of a few bruises, and the motocycle passed along.

While coming back through Rogers Park the Macy carriage met a hack which did not give the right of way. In trying to turn out, the tire of the motocycle slipped and its front wheel collided with the rear wheel of the hack. By the collision four spokes were badly chipped and the steering gear bent so as to be almost useless. Fortunately, the gauge of the vehicle was the same in width as the street-car tracks, and by keeping the car track it managed to reach the second relay station a mile farther on.

The third and last motocycle to pass the second relay station was the Mueller machine. Several stops had been made to oil and to fix the clutch, which had been bent by the rough roads. After replenishing the fuel and repairing, the machine started again and was working smoothly as it disappeared around a curve in Clark Street.

Duryea Reaches Douglas Park

WET and cold, darkness already coming on, and not a motocycle in sight, the small boys and the little girls and the older folks went home. Consequently when, a few minutes before six o’clock, the Duryea motor came through Douglas Park, laboring with a very bad roadway, there was no one to greet it on California Avenue but a representative of the Times-Herald. Ahead of the machine drove the umpire, and after the good wheeling on California Avenue was found he had a lively time keeping ahead of the vehicle. On Thirty-fourth Street and the first approaches to Western Avenue the roadbed was comparatively hard, and the motor made magnificent time, traveling one pace at the rate of eight miles an hour with ease. Lacking spectators, except here and there a solitary workman on his way home, or the belated watchman of one of the ill-smelling soap factories of the district hastening to his odorous place of duty, the men on the motor gave vent to war whoops, cheers, cat calls and other manifestations of joy over the victory they were winning. Western Avenue Boulevard was not so easy going. The path was poorly broken and the underbed rough. Progress to Fifty-fifth Street was slow and tedious, but the motor held to her work without a break. As the boulevard was turned, onto the final run, on the home stretch the cry rang out „This is 5:5:55.“

To Ashland Avenue but one sleigh was passed. The darkness was on, and hidden behind two horse-moving rigs the motocycle was comparatively unnoticed. But at Halstead a woman crossing the street with an escort caught sight of the strange rig and jumped back from the crossing, frightened. On the opposite corner at the drug store a crowd of men cheered. Young boys began to chase the motocycle and shout, but they could not keep up.

No delays were met with but stoppage for gasoline and the holding of the motor at the crossing of the Fort Wayne Road by passing trains for four minutes. After this the run to South Park and then to the starting line of the morning was uneventful. Not fifty people saw the last stages of the finish or knew that the Duryea had established a world’s record in the capacity of a motocycle to conquer even King Winter himself. It was just 7:18 when Frank Duryea threw himself out of the seat of the motor and announced the end. His hand was grasped by the few who saw him cross the line. The congratulations were hearty. The crowd of travelers were hungry. The Duryea was wheeled about and started for her quarters on Sixteenth Street.

At 8:53, with John Lundy, one of the judges, holding the watch, the Mueller motor crossed the line, second in the race, and, considering the lateness of the hour at which she started, really only twenty-four or twenty-five minutes behind the Duryea.

Her journey through the parks and boulevards of the city proper was even more lonesome than that of the Duryea to the spectators. An enthusiast might be found at some point who had waited all the afternoon for the sight, but these were few. The gayeties of the evening had called away the large and jolly crowds of the morning, and only the officials of the race and the reporters saw the end of the great battle against the snow and a too kindly sun.

Lieutenant Samuel Rodman, umpire for the Macy motocycle, reported shortly after twelve o’clock that the Macy had been compelled to quit the race at California and Ogden avenues at 6:15 P.M. At that time they were only twenty-five minutes behind the Duryea machine, and were ahead of the Mueller motocycle. Their motor gave out at that point, and although they labored with it for five hours, or until 11:30, they were unable to make it run satisfactorily again. They consequently abandoned the race. The Mueller machine passed them while they were trying to repair the defects of the motor, but they could not follow it.

Lieutenant Rodman was convinced that the collision which the Macy had on Evanston Avenue early in the day with an ignorant, obstinate coachman, and which injured the steering apparatus, so destroyed the adjustment of that important mechanism that after that time the motor could not be run at its full capacity and eventually broke down altogether. Still, at California and Ogden avenues, where it quit, the Macy was second in the race, with a fair show of overtaking the Duryea and producing a neck-and-neck finish.

Thus closed America’s first horseless-carriage race.

Confession

I LIKE to see the home team win

Whatever game they’re playing in,

And any time they lose a yard

I want to see them come back hard.

I can’t abide the cultured throng

Who always say our crowd is wrong –

Those high, defeatist Sons of Light

To whom their land is never right.

I’m no „true sport“; I would not choose

To see my friends and neighbors lose.

Though worth must be the only test,

I want our own to be the best.

I hope that we’re the best by far,

And, worst of all, I think we are!

-Arthur Guiterman.