Text and jpegs by courtesy of hathitrust.org www.hathitrust.org, compiled by motorracinghistory.com

MOTOR AGE Vol. XXV, No. 22 Chicago, May 28, 1914

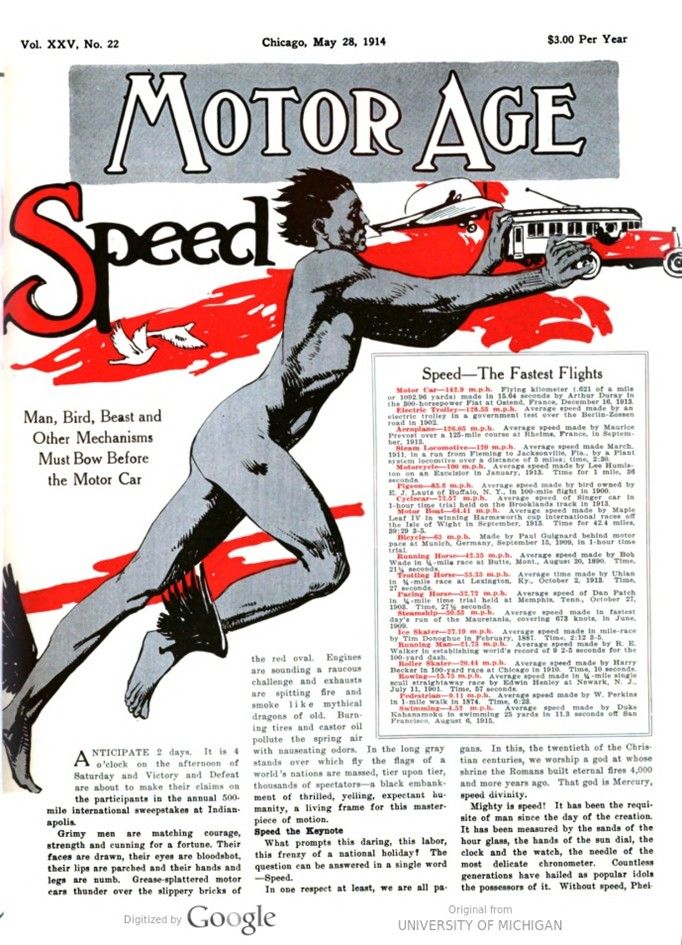

Speed

Man, Bird, Beast and Other Mechanisms Must Bow Before the Motor Car

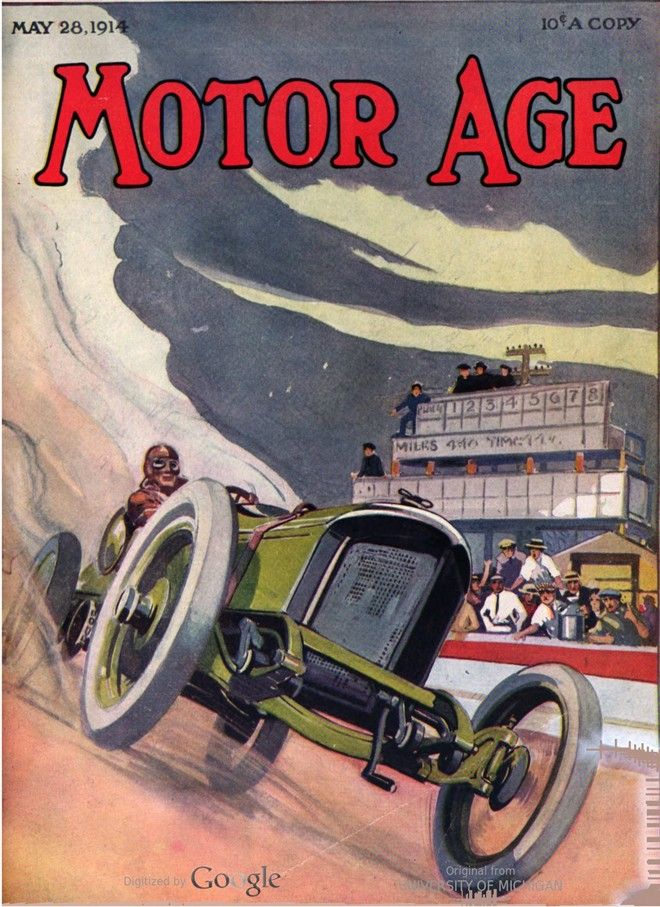

ANTICIPATE 2 days. It is 4 o’clock on the afternoon of Saturday and Victory and Defeat are about to make their claims on the participants in the annual 500-mile international sweepstakes at Indianapolis.

Grimy men are matching courage, strength and cunning for a fortune. Their faces are drawn, their eyes are bloodshot, their lips are parched and their hands and legs are numb. Grease-splattered motor cars thunder over the slippery bricks of the red oval. Engines are sounding a raucous challenge, and exhausts are spitting fire and smoke like mythical dragons of old. Burning tires and castor oil pollute the spring air with nauseating odors. In the long gray stands over which fly the flags of a world’s nations are massed, tier upon tier, thousands of spectators-a black embankment of thrilled, yelling, expectant humanity, a living frame for this masterpiece of motion.

Speed-The Fastest Flights

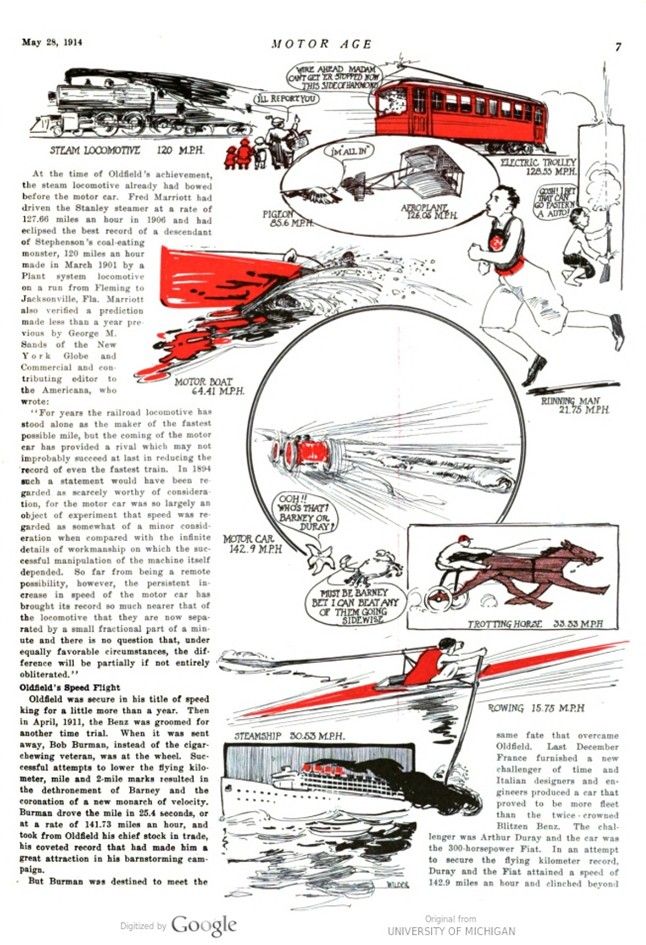

Motor Car-142.9 m.p.h. Flying kilometer (.621 of a mile or 1092.96 yards) made in 15.64 seconds by Arthur Duray in the 300-horsepower Fiat at Ostend, France, December 16, 1913.

Electric Trolley-128.55 m.p.h. Average speed made by an electric trolley in a government test over the Berlin-Zossen road in 1902.

Aeroplane-126.05 m.p.h. Average speed made by Maurice Prevost over a 125-mile course at Rheims, France, in September, 1913.

Steam Locomotive-120 m.p.h. Average speed made March, 1911, in a run from Fleming to Jacksonville, Fla., by a Plant system locomotive over a distance of 5 miles; time, 2:30.

Motorcycle-100 m.p.h. Average speed made by Lee Humiston on an Excelsior in January, 1913. Time for 1 mile, 36 seconds.

Pigeon-85.6 m.p.h. Average speed made by bird owned by E. J. Lautz of Buffalo, N. Y., in 100-mile flight in 1900. Cyclecar-72.57 m.p.h. Average speed of Singer car in 1-hour time trial held on the Brooklands track in 1913.

Motor Boat-64.41 m.p.h. Average speed made by Maple Leaf IV in winning Harmsworth cup international races off the Isle of Wight in September, 1913. Time for 42.4 miles, 39:29 3-5.

Bicycle-63 m.p.h. Made by Paul Guignard behind motor pace at Munich, Germany, September 15, 1909, in 1-hour time trial.

Running Horse 42.35 m.p.h. Average speed made by Bob Wade in 4-mile race at Butte, Mont., August 20, 1890. Time, 21 seconds. Average time made by Uhlan Ky., October 2, 1913. Time,

Trotting Horse-33.33 m.p.h. in 4-mile race at Lexington, 27 seconds.

Pacing Horse-32.72 m.p.h. Average speed of Dan Patch in 4-mile time trial held at Memphis, Tenn., October 27, 1903. Time, 27 seconds.

Steamship-30.53 m.p.h. Average speed made in fastest day’s run of the Mauretania, covering 673 knots, in June, 1909.

Ice Skater-27.19 m.p.h. Average speed made in mile-race by Tim Donoghue in February, 1887. Time, 2:12 3-5.

Running Man-21.75 m.p.h. Average speed made by R. E. Walker in establishing world’s record of 9 2-5 seconds for the 100-yard dash.

Roller Skater-20.44 m.p.h. Average speed made by Harry Becker in 100-yard race at Chicago in 1910. Time, 10 seconds.

Rowing-15.75 m.p.h. Average speed made in 4-mile single scull straightaway race by Edwin Henley at Newark, N. J., July 11, 1901. Time, 57 seconds.

Pedestrian-9.11 m.p.h. Average speed made by W. Perkins in 1-mile walk in 1874. Time, 6:23.

Swimming-4.52 m.p.h. Average speed made by Duke Kahanamoku in swimming 25 yards in 11.3 seconds off San Francisco, August 6, 1915.

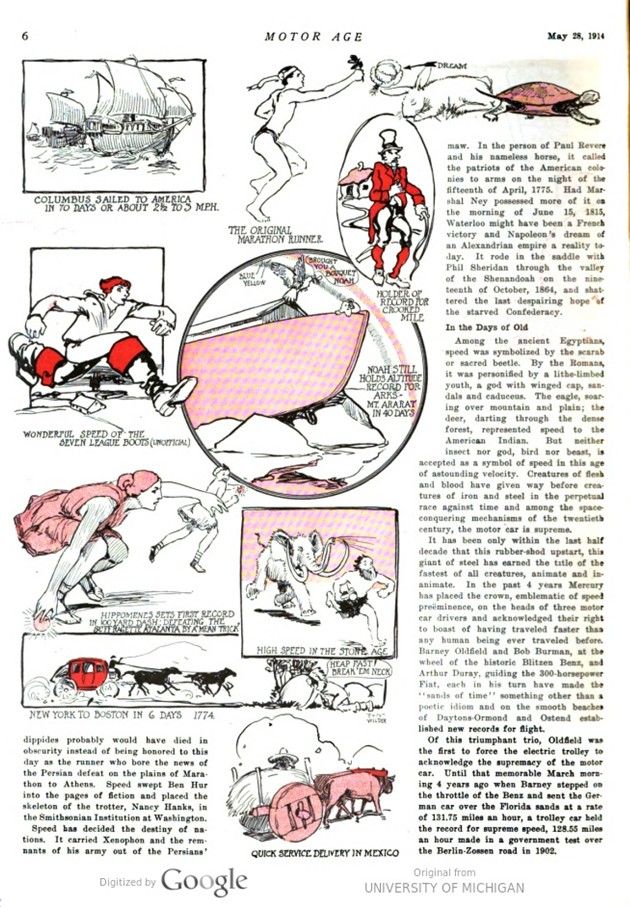

* Captions to accompanying drawings. *

COLUMBUS SAILED TO AMERICA IN 70 DAYS OR ABOUT 2½ TO 3 MPH – THE ORIGINAL MARATHON RUNNER

HOLDER OF RECORD FOR CROOKED MILE – NOAH STILL HOLDS ALTITUDE RECORD FOR ARKS – MT. ARARAT IN 40 DAYS

WONDERFUL SPEED OF THE SEVEN LEAGUE BOOTS (UNOFFICIAL)

HIPPOMENES SETS FIRST RECORD IN 100 YARD DASH; DEFLATING THE SUFRAGETTE ATALANTA BY A “MEAN TRICK”

HIGH SPEED IN THE STONE AGE – NEW YORK TO BOSTON IN 6 DAYS 1774 – QUICK SERVICE DELIVERY IN MEXICO

STEAM LOCOMOTIVE 120 M.PH. – ELECTRIC TROLLEY 128.55 MPH.

(WIRE AHEAD MADAM CAN’T GET ER STOPPED NOW THIS SIDE OF HAMMOND – ILL REPORT YOU.

GOSH! I BET THAT CAN GO FASTER ‘N A AUTO !

PIGEON 85.6 MPH. – AEROPLANE 126.05 MPH. – MOTORBOAT 64.41 M.P.H. – RUNNING MAN 21.75 M.PH

MOTOR CAR 142.9 M.P.H. – OOH!! WHO’S THAT?

BARNEY OR DURAY? MUST BE BARNEY BET I CAN BEAT ANY OF THEM GOING SIDEWISE

TROTTING HORSE 33.33 M.PH. – STEAMSHIP 30.53 M.PH. – ROWING 15.75 M.P.H

Speed the Keynote

What prompts this daring, this labor, this frenzy of a national holiday? The question can be answered in a single word – Speed.

In one respect at least, we are all pagans. In this, the twentieth of the Chris- tian centuries, we worship a god at whose shrine the Romans built eternal fires 4,000 and more years ago. That god is Mercury, speed divinity.

Mighty is speed! It has been the requisite of man since the day of the creation. It has been measured by the sands of the hourglass, the hands of the sun dial, the clock and the watch, the needle of the most delicate chronometer. Countless generations have hailed as popular idols the possessors of it. Without speed, Pheidippides probably would have died in obscurity instead of being honored to this day as the runner who bore the news of the Persian defeat on the plains of Marathon to Athens. Speed swept Ben Hur into the pages of fiction and placed the skeleton of the trotter, Nancy Hanks, in the Smithsonian Institution at Washington.

Speed has decided the destiny of nations. It carried Xenophon and the remnants of his army out of the Persians‘ maw., In the person of Paul Revere and his nameless horse, it called the patriots of the American colonies to arms on the night of the fifteenth of April 1775. Had Marshal Ney possessed more of it on the morning of June 15, 1815, Waterloo might have been a French victory and Napoleon’s dream of an Alexandrian empire a reality today. It rode in the saddle with Phil Sheridan through the valley of the Shenandoah on the nineteenth of October, 1864, and shattered the last despairing hope of the starved Confederacy.

In the Days of Old

Among the ancient Egyptians, speed was symbolized by the scarab or sacred beetle. By the Romans, it was personified by a lithe-limbed youth, a god with winged cap, sandals and caduceus. The eagle, soaring over mountain and plain; the deer, darting through the dense forest, represented speed to the American Indian. But neither insect nor god, bird nor beast, is accepted as a symbol of speed in this age of astounding velocity. Creatures of flesh and blood have given way before creatures of iron and steel in the perpetual race against time and among the space. conquering mechanisms of the twentieth century, the motor car is supreme.

It has been only within the last half decade that this rubber-shod upstart, this giant of steel has earned the title of the fastest of all creatures, animate and inanimate. In the past 4 years Mercury has placed the crown, emblematic of speed preëminence, on the heads of three motor car drivers and acknowledged their right to boast of having traveled faster than any human being ever traveled before. Barney Oldfield and Bob Burman, at the wheel of the historic Blitzen Benz, and Arthur Duray, guiding the 300-horsepower Fiat, each in his turn have made the „sands of time” something other than a poetie idiom and on the smooth beaches of Daytons-Ormond and Ostend established new records for flight.

Of this triumphant trio, Oldfield was the first to force the electric trolley to acknowledge the supremacy of the motor car. Until that memorable March morning 4 years ago when Barney stepped on the throttle of the Benz and sent the German car over the Florida sands at a rate of 131.75 miles an hour, a trolley car held the record for supreme speed, 128.55 miles an hour made in a government test over the Berlin-Zossen road in 1902.

At the time of Oldfield’s achievement, the steam locomotive already had bowed before the motor car. Fred Marriott had driven the Stanley steamer at a rate of 127.66 miles an hour in 1906 and had eclipsed the best record of a descendant of Stephenson’s coal-eating monster, 120 miles an hour made in March 1901 by a Plant system locomotive on a run from Fleming to Jacksonville, Fla. Marriott also verified a prediction made less than a year previous by George M. Sands of the New York Globe and Commercial and con- tributing editor to the Americana, who wrote:

„For years the railroad locomotive has stood alone as the maker of the fastest possible mile, but the coming of the motor car has provided a rival which may not improbably succeed at last in reducing the record of even the fastest train. In 1894 such a statement would have been regarded as scarcely worthy of consideration, for the motor car was so largely an object of experiment that speed was regarded as somewhat of a minor consideration when compared with the infinite details of workmanship on which the successful manipulation of the machine itself depended. So far from being a remote possibility, however, the persistent increase in speed of the motor car has brought its record so much nearer that of the locomotive that they are now separated by a small fractional part of a minute and there is no question that, under equally favorable circumstances, the difference will be partially if not entirely obliterated.“

Oldfield’s Speed Flight

Oldfield was secure in his title of speed king for a little more than a year. Then in April, 1911, the Benz was groomed for another time trial. When it was sent away, Bob Burman, instead of the cigar-chewing veteran, was at the wheel. Successful attempts to lower the flying kilometer, mile and 2-mile marks resulted in the dethronement of Barney and the coronation of a new monarch of velocity. Burman drove the mile in 25.4 seconds, or at a rate of 141.73 miles an hour, and took from Oldfield his chief stock in trade, his coveted record that had made him a great attraction in his barnstorming campaign.

But Burman was destined to meet the same fate that overcame Oldfield. Last December France furnished a new challenger of time, and Italian designers and engineers produced a car that proved to be more fleet than the twice crowned Blitzen Benz. The challenger was Arthur Duray, and the car was the 300-horsepower Fiat. In an attempt to secure the flying kilometer record, Duray and the Fiat attained a speed of 142.9 miles an hour and clinched beyond all doubt the claim of the motor car to world’s speed honors.

Just as 8 years ago the supremacy of the locomotive was challenged by the motor car, so today the latter has a dangerous rival in another mechanical upstart, the aeroplane which has an unofficial record of 165 miles an hour in a flight with a strong wind behind it. In fact, Duray’s Fiat might have to exert itself to defeat the holder of the world’s speed record in the air, the biplane in which Maurice Prevost averaged 126.05 miles per hour in the Gordon Bennett cup race of 1913. Compare this record with that of 1909-49.99 miles per hour made by Leon Delagrange at Doncaster, England – and the battle with time as waged by the aeroplane is as spectacular and sensational as the attempts of the motor car to crowd miles within a fleeting minute.

Man, beast, bird and other mechanisms, however, have yet to equal, let alone better, the official record of the motor car. Match Duray and the Fiat against the swiftest aero plane, steam locomotive, electric trolley, steam boat, motor boat or motorcycle; against the fleetest pigeon, trotter, pacer or running horse; against the fastest runner, swimmer, skater or rower and the combination of driver and motor car could give them all a handicap and defeat them in a race of any distance from 100 yards up. This sounds like an extravagant, an arrogant claim, but compare the speed records and you I will find that it is true.

Just Supposing

Merely for the sake of illustration and with no intention of joining the overcrowded ranks of the promoters, let us pit Duray’s Fiat against Prevost’s aero plane. Here’s a tip straight from the feed box-take the motor car at any odds you can get. In a 125-mile race, the Fiat could give the biplane a start of 6 minutes and cross the tape a winner by 36 seconds, provided each equals the speed made in establishing their world’s records. Duray’s time would be 52 minutes 48 seconds; Prevost ’s, 59 minutes 24 seconds.

In a 5-mile race with the holder of the locomotive speed record of 120 miles an hour, the 300-horsepower Fiat could allow its giant rival a 20-second handicap and win by a margin of 6 seconds. The times of the two contestants would be: Locomotive, 2 minutes 30 seconds; motor car, 2 minutes 6 seconds.

It would be a shame for Duray to take the money in a brush with the fastest of steamships, the Mauretania, which established a speed record for ocean greyhounds in June, 1909, when it averaged 30.53 miles per hour in a day’s run of 673 knots. E. Mackey Edgar’s „Maple Leaf IV“-winner of the Harmsworth cup motorboat races of 1913 would give the Fiat a more exciting race, if the two were matched, than the Mauretania. The international trophy victor covered a 42.4-mile course in 39 minutes and 29 3-5 seconds, at an average speed of 64.41 miles per hour. The Fiat’s time for the same distance would be 16 minutes 54 seconds.

In a 1-mile race with Lee Humiston, holder of the motorcycle 1-mile record of 36 seconds, Duray would finish 10.8 seconds ahead of his rival, the average speed of the Fiat for 1 mile being 25.2 seconds.

Motor Car vs. Running Horse

Salvator, holder of the 1-mile straightaway record of 1 minute 35 seconds for running horses; Uhlan, king of trotters, with a mile mark of 1 minute 542 seconds; and the pacer, Dan Patch, who holds the 1-mile record for side-wheelers of 1 minute 55 seconds, would be among the also rans in a race with the Fiat, if any tout should step up and ask you. The average speed of the three equine champions is as follows: Salvator, 37.6 miles per hour; Uhlan, 31.39 miles per hour; Dan Patch, 32.43 miles per hour. In a match race, Duray would lap them four times and have yards to spare.

R. E. Walker, the South African sprinter who holds the world’s record of 9 2-5 seconds for the 100 yards dash, would make a very poor showing indeed in a contest with the Fiat which, at a speed of 142.9 miles per hour, would cover the century in 1.52 seconds. The champion mile runner, W. G. George of England, with a mark of 4 minutes 12¾ seconds, would be an even more hopeless contender as his average speed is but 14.2 miles per hour.

Now for a literary shot of hop, a drug fiend’s dream of speed and the victory of a blur in the 500-mile race. Quick, Watson, the needle!

Duray at the Speedway

Arthur Duray is at the tape, not in the diminutive Peugeot that he will drive Saturday but at the wheel of the greatest of space-conquerors, the 300-horsepower Fiat. A bomb breaks! The crowd is on its feet. With motors roaring and exhausts popping, the cars are sent away. The Fiat leaps to the front. Duray sweeps around the tortuous turns without diminishing his speed, at the same furious death-inviting clip as when he established the world’s record of 142.9 miles per hour in his trial at Ostend.

As he whirls around the resonant red bowl, he is but a streak, a flash. Not once does he stop either for fuel or new tires. His time for each of the 2½ mile laps is 1 minute 3 seconds. The race started at 10 o’clock. He gets the checkered flag just as the hands of your watch are about to point to half past one. He has covered the 5 centuries in 3 hours, 29 minutes, 52.8 seconds. At this time in 1912, Dawson, in his National, would have traveled only 275 of the 500 miles.

Champions of the motor car need not depend alone on Duray’s Fiat to defend the speed title against all comers. There are other gasoline-driven monsters of steel almost as fast and which have established sensational records in competition and sustained flight, cars that have crowded 100 or more miles within a floating hour and more than ten times 100 miles within 12 hours.

There is the mighty twelve-cylinder Sunbeam that ground Time beneath its wheels on the Brooklands speedway twice within a week last October. In its premier appearance, it averaged 110.75 miles per hour and defeated eleven other contestants in an 8.5-mile handicap race. This record is all the more remarkable in that it was made in competition and in a handicap event. Starting from scratch, Chassagne, the Sunbeam driver, was forced to thread his way through a closely bunched field. No doubt, on a clear track, the average speed would have been much greater. For a single circuit of the 2.75-mile course, the Sunbeam averaged 118.58 miles per hour which for the longer distance is almost as creditable as the 142.9 miles per hour average of Duray in driving the kilometer.

Sunbeam’s Hour Record

Six days after this triumphant debut, the English speed creation was sent away to shatter the 1-hour record of 106 miles 387 yards established by Goux and the Peugeout at Brooklands in April. Holding to an average lap time of 1 minute 32 seconds in order to save tires and breaking the 50 and 100-mile marks en route, Chassagne, at the expiration of 60 minutes, had covered 107 miles 1,672 yards, which still stands as record.

John Bull has another formidable defender of the motor car’s speed laurels in the six-cylinder Sunbeam that averaged 89.91 miles an hour in establishing the 12- hour record of 1.078 miles, 460 yards. This performance eclipsed the best previous mark, that of the Hornstead-Scott Argyle, by approximately 164 miles. The Sunbeam is the first car to crowd 1,000 or more miles within 12 hours. What is could do if it went after the 24-hour record is problematical, but in all probability it easily could beat Edge’s mark.

Mighty is the motor car! It is the personification of speed.

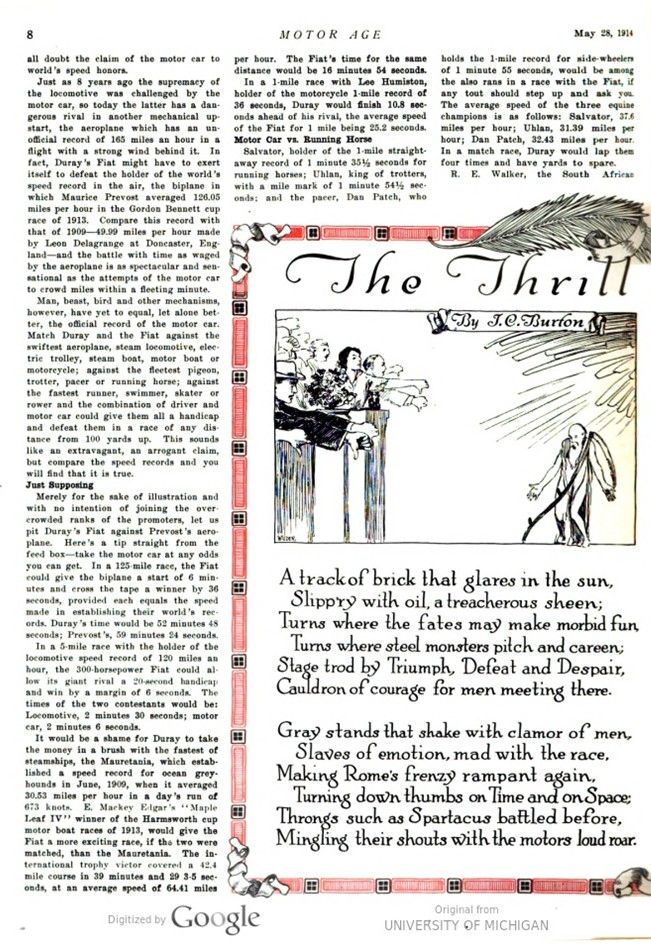

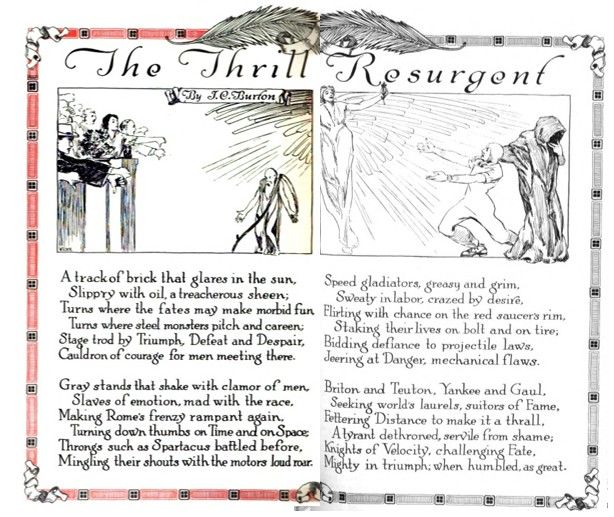

The Thrill Resurgent – By J.C.Burton

A track of brick that glares in the sun,

Slippry with oil, a treacherous sheen;

Turns where the fates may make morbid fun,

Turns where steel monsters pitch and careen;

Stage trod by Triumph, Defeat and Despair,

Cauldron of courage for men meeting there.

Gray stands that shake with clamor of men,

Slaves of emotion, mad with the race,

Making Rome’s frenzy rampant again,

Turning down thumbs on Time and on Space;

Throngs such as Spartacus battled before,

Mingling their shouts with the motors loud roar.

Speed gladiators, greasy and grim,

Sweaty in labor, crazed by desire,

Flirting with chance on the red saucer’s rim,

Staking their lives on bolt and on tire;

Bidding defiance to projectile laws,

Jeering at Danger, mechanical flaws.

Briton and Teuton, Yankee and Gaul,

Seeking world’s laurels, suitors of Fame,

Fettering Distance to make it a thrall,

A tyrant dethroned, servile from shame;

Knights of Velocity, challenging Fate,

Mighty in triumph; when humbled, as great.