This article was written by the well known American reporter William F. Bradley. Being stationed in Paris, he wrote for several US automotive magazines, already since beginning of the 1900’s. Here it is described how much American- and European engines differ. Athough Alfa Romeos made a one-two finish, thereby clinching the championshipt; he American Duesenbergs made a good appearance; Tommy Milton finished fourth and Peter Kreis even set the fastest lap.

Text and jpegs by courtesy of hathitrust.org www.hathitrust.org, compiled by motorracinghistory.com

Automotive Industries, Vol. LIII, No. 14-18, October 8, 1925

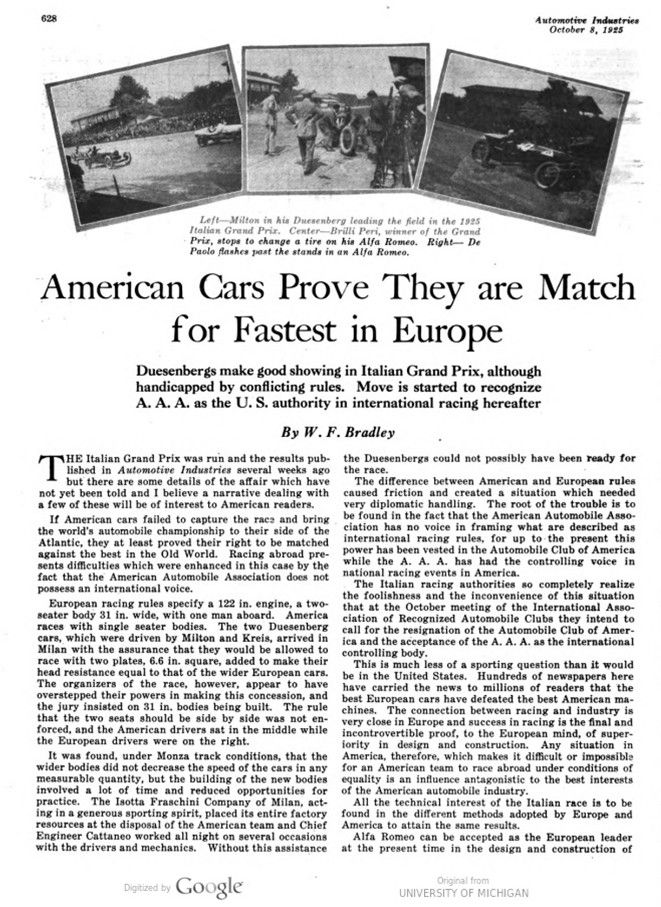

American Cars Prove They are Match for Fastest in Europe

Duesenbergs make good showing in Italian Grand Prix, although handicapped by conflicting rules.

Move is started to recognize A. A. A. as the U. S. authority in international racing hereafter

By W. F. Bradley

THE Italian Grand Prix was run and the results published in Automotive Industries several weeks ago but there are some details of the affair which have not yet been told, and I believe a narrative dealing with a few of these will be of interest to American readers.

If American cars failed to capture the race and bring the world’s automobile championship to their side of the Atlantic, they at least proved their right to be matched against the best in the Old World. Racing abroad presents difficulties which were enhanced in this case by the fact that the American Automobile Association does not possess an international voice.

European racing rules specify a 122 in. engine, a two-seater body 31 in. wide, with one man aboard. America races with single seater bodies. The two Duesenberg cars, which were driven by Milton and Kreis, arrived in Milan with the assurance that they would be allowed to race with two plates, 6.6 in. square, added to make their head resistance equal to that of the wider European cars. The organizers of the race, however, appear to have overstepped their powers in making this concession, and the jury insisted on 31 in. bodies being built. The rule that the two seats should be side by side was not enforced, and the American drivers sat in the middle while the European drivers were on the right.

It was found, under Monza track conditions, that the wider bodies did not decrease the speed of the cars in any measurable quantity, but the building of the new bodies involved a lot of time and reduced opportunities for practice. The Isotta Fraschini Company of Milan, acting in a generous sporting spirit, placed its entire factory resources at the disposal of the American team and Chief Engineer Cattaneo worked all night on several occasions with the drivers and mechanics. Without this assistance the Duesenbergs could not possibly have been ready for the race.

The difference between American and European rules caused friction and created a situation which needed very diplomatic handling. The root of the trouble is to be found in the fact that the American Automobile Association has no voice in framing what are described as international racing rules, for up to the present this power has been vested in the Automobile Club of America while the A. A. A. has had the controlling voice in national racing events in America.

The Italian racing authorities so completely realize the foolishness and the inconvenience of this situation that at the October meeting of the International Association of Recognized Automobile Clubs they intend to call for the resignation of the Automobile Club of America and the acceptance of the A. A. A. as the international controlling body.

This is much less of a sporting question than it would be in the United States. Hundreds of newspapers here have carried the news to millions of readers that the best European cars have defeated the best American machines. The connection between racing and industry is very close in Europe and success in racing is the final and incontrovertible proof, to the European mind, of superiority in design and construction. Any situation in America, therefore, which makes it difficult or impossible for an American team to race abroad under conditions of equality is an influence antagonistic to the best interests of the American automobile industry.

All the technical interest of the Italian race is to be found in the different methods adopted by Europe and America to attain the same results.

Alfa Romeo can be accepted as the European leader at the present time in the design and construction of modern 122 in. racing cars and Duesenberg can claim a similar position in America.

European engineers were amazed to find that Duesenberg was getting results with a cheap and economical design and construction which they had been able to attain only by much more expensive methods. It was sometimes difficult to convince them that the Duesenberg engines had white metal for the main and connecting rod bearings, for their experience has been that only the more costly roller bearing and its special type of shaft will stand up on high efficiency engines running at 5000 revolutions and more. The use of a detachable cylinder head also created surprise, for European experience is that a joint at this point cannot be made gas tight.

There was nothing in common between the Alfa Romeo and the Duesenberg engines. The Alfa Romeo represents a European type developed first in the Fiat factory by such engineers as Cappa, Jano and Bertarione and now to be found, with various modifications, in half a dozen European factories.

Rootes Type Blower Used

Steel cylinders, roller bearings for crankshaft and connecting rods, two overhead camshaft with rear end drive by a train of spur pinions, and a Rootes type blower running at or about engine speed are the main features of this type of engine. Alfa Romeo made use of a special type of fuel, the nature of which was not revealed. According to the popular report-repeated for what it is worth-Mussolini had given orders that it should be kept secret in the interests of the nation. It was only necessary to stand near the cars to realize that there was an important proportion of wood alcohol and ether in the composition.

This special fuel enabled a compression ratio of 7.5 to 1 to be used. The pressure obtained by the blower could not be ascertained. Other European firms have employed an equally high compression ratio, but when a super-charger has been added they have had to reduce it. Only the special fuel allowed the higher pressure to be used on the Alfa Romeos.

European racing cars, without exception, use the Rootes type blower, Alfa Romeo, Fiat, Diatto and Mercedes placing it before the carburetor and Sunbeam and Darracq placing it after the carburetor.

Among the features of the Alfa Romeo blower are the use of two different gear ratios, the blower being slightly geared up in relation to the engine, and a free wheel overrunning device allowing the blower to overrun the engine when the latter is cut out. This avoided flat spots in pick up and was valuable on a set of roads calling for a wide range of engine speed.

The Alfa Romeo engineers succeeded in getting a high-power output at comparatively low engine speeds. They obtained 100 h.p. at 3000 revolutions and touched the peak of their power curve at rather more than 5000 revolutions. On several other European makes the maximum power was obtained at a much higher number of revolutions, but the greater power gave no advantage, for road conditions did not make it possible to utilize the engines at the highest number of revolutions.

The story of the race is easily told. Kreis took the lead on the second lap, but driving too fast he spun around on one of the curves, was unable to withdraw the clutch and broke the second gear in the transmission.

Milton was delayed a few seconds on the starting line and had to go right through the group of slower 91 in. cars running with the 122 in. models in this race. For twelve laps, (72 miles) he trailed the three Alfa Romeos, then on the thirteenth lap caught up and passed De Paolo. Near thirty laps he was on the tails of the two other Alfa Romeos, and when the Italian cars stopped for gas and tires he went into the lead.

At forty laps, half distance, while still leading, Milton made his first stop or tires and gas, but on the following lap he had to stop again owing to a broken oil line to the right hand camshaft. The repair cost him 26 minutes and removed all chance of winning the race.

In addition to this Milton had broken his right rear shock absorber very early in the race, and had broken the countershaft in his transmission during the fifth lap. He was consequently obliged to run on top, although the course required two gear changes per lap.

The Alfa Romeos had developed a lot of trouble prior to the race and were not running to their usual standard. Milton had the advantage in maximum speed, but with a broken shock absorber his car had a tendency to snake on the turns and his average speed was low on this winding course.

The twenty-six minutes occupied in repairing the broken oil line dropped Milton from the leading position he had occupied for seven laps down to eighth position, behind all the Alfa Romeos and also in the rear of four of the 91 in. Bugattis. Realizing that he had no chance of winning, Milton took things easy from this point on and although he got ahead of the Bugattis again, with the exception of the one driven by Constantini, he did not attempt to beat the Alfa Romeos.

Although running on high the whole time and handicapped by the broken shock absorber, Milton’s position relative to the Alfa Romeos never varied a yard over distances of fifty or sixty miles. His engine was pulling perfectly, and had his transmission been equally good he felt he could have made an easy win.

Peter De Paolo, according to his usual practice, turned over the wheel of his car to a relief driver for a few laps in the middle of the race. He had to contend with minor troubles of a mechanical nature and the choke tube of one of the carburetors having become displaced, the entire carburetor had to be changed after about three-quarter distance had been covered. De Paolo never got the lead, his best position in the race being second.

Bugattis Stage Own Race

There was not much competition among the 91 in. cars, excepting that provided among themselves by the four drivers of the Bugatti team.

Two Chiribiris went out rather early, one of them turning over without any damage to the driver. Eldridge, the English driver, came with a car which had never been run and did not endure for more than a dozen laps.

Jules Goux took the lead of the 91 in. group and held it for 450 miles, when he was forced out with broken valves. This gave Constantini, who had been held back at the beginning by spark plug trouble the necessary opportunity to get in the lead. The fastest lap among the 91 in. cars was made by Constantini at 92.91 miles an hour, and his average for the 500 miles was 86.479 miles an hour.

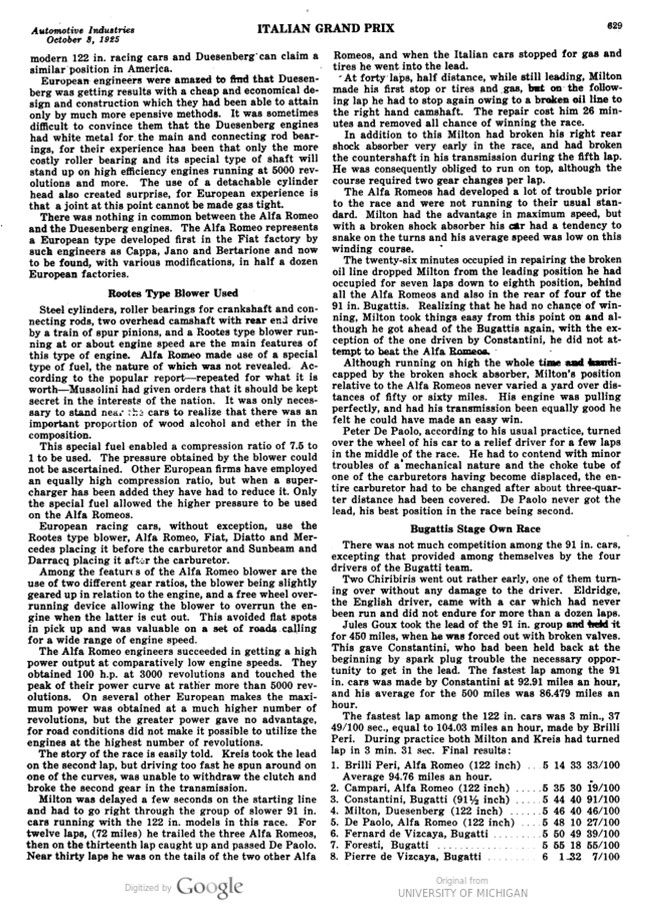

The fastest lap among the 122 in. cars was 3 min., 37 49/100 sec., equal to 104.03 miles an hour, made by Brilli Peri. During practice both Milton and Kreis had turned lap in 3 min. 31 sec. Final results:

1. Brilli Peri, Alfa Romeo (122 inch) 5 14 33 33/100 – Average 94.76 miles an hour.

2. Campari, Alfa Romeo (122 inch) 5 35 30 19/100

3. Constantini, Bugatti (91½ inch) 5 44 40 91/100

4. Milton, Duesenberg (122 inch) 5 46 40 46/100

5. De Paolo, Alfa Romeo (122 inch) 5 48 10 27/100

6. Fernard de Vizcaya, Bugatti 5 50 49 39/100

7. Foresti, Bugatti 5 55 18 55/100

8. Pierre de Vizcaya, Bugatti 6 1 32 7/100

Foto’s page 32.

Left – Milton in his Duesenberg leading the field in the 1925 Italian Grand Prix. Center – Brilli Peri, winner of the Grand Prix, stops to change a tire on his Alfa Romeo.

Right – De Paolo flashes past the stands in an Alfa Romeo.